Top 10 Little-Known Facts About Color

10 Mummy brown

In the 16th century, a new shade of brown paint started appearing in European art called “Mummy Brown”. You may think this is simply a creative name, but in fact, this paint was actually made of real crushed ancient Egyptians. In the 19th, “Egyptomania” spread across Europe and the United States, as people used mummies as decor, medicine, paper, and even party games at mummy unrolling events.[1] The exact technique for preparing the color varied quite a bit, and today it is almost impossible to tell if a painting used the substance through any kind of analysis, but all of its variations included actual mummy. But not everyone even knew what the paint was really made of. When one painter, Edward Burnes-Jones, found out the true origins of the material he had been using he held an impromptu funeral for the mummy in his backyard.[2] But much like ancient Egypt itself, the reign of the color had to come to an end. In 1964, the creator of mummy brown paint reported that they had run out of mummies, saying “We might have a few odd limbs lying around somewhere but not enough to make any more paint”.[3] If you want to recreate the shade today, you might have some trouble getting the materials.

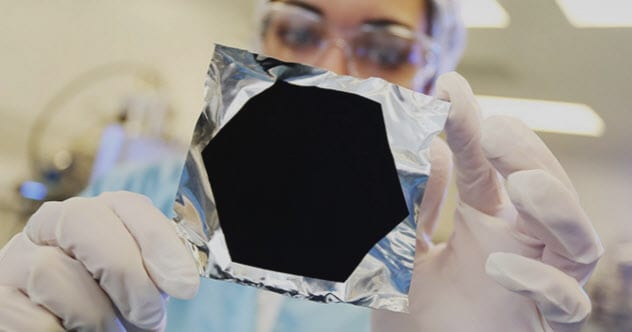

9 Vantablack

Vantablack is one of the darkest colors known to mankind. Developed by British company Surrey NanoSystems in the early 2000s, it can absorb 99.965% of visible light.[4] It held the Guinness World Record for darkest man-made substance until a material with a much less catchy name known as “dark chamaleon dimers” knocked it out of the top spot in 2015.[5] It can be used to keep light out of telescopes and infrared cameras and potentially collect solar energy. It may also have military applications, such as intense camouflage.[6] However, if you use vantablack paint to make a modern art piece or decorate your bedroom, you will probably be out of luck. Unless your name is Anish Kapoor, of course, because he holds the exclusive licensing to use the product in art. Kapoor, who is well-known for creating the bean-shaped “Cloud Gate” sculpture in Chicago, has received sharp criticism for trying to keep an entire color to himself. Fellow artist Stuart Semple hit back by creating several other colors, including “Pinkest Pink”, “Black 2.0”, “Black 3.0”, and “Diamond Dust”, which every single person in the world is allowed to use… except Anish Kapoor.[7] Massachusetts company NanoLab also created a similar substance to Vantablack known as Singularity Black which is available for the public, so if you really want something to be as dark as possible, you can give them a call.[8]

8 Tyrian Purple

Royal purple hues have been associated with nobility for centuries and the connection lingers to this day. During the Roman Empire, any non-noble who dared to try to wear purple could be executed. Queen Elizabeth I forbid anyone but her family from wearing it as part of the Sumptuary Laws that governed what each social class could wear. This reddish-purple was even thought to look similar to dried blood, connecting royals to the idea of a divine bloodline. It became popular among the ruling class in Egypt, Persia, and the Roman Empire and carried through until the mid-1500s.[9] The reason why purple dye was so rare is that it was incredibly difficult and expensive to produce. The Phoenician city Tyre was the main producer of the dye, which was called Tyrian purple or royal or Imperial purple To extract the pigment, hundreds of thousands of sea snails had to be collected, cracked, and exposed to sunlight (which produced a truly horrible smell). This process required up to 250,000 snails for one ounce of dye, which made it prohibitively expensive for almost everyone,[10] and the snails were only native to the Mediterranean. The clothing made from this dye never faded, and it was literally worth its weight in gold.[11] In 1856, teenage chemist William Henry Perkin accidentally invented a much cheaper purple dye while working on anti-malaria treatment. This new dye, eventually called “mauve”, helped purple become available to everyone.

7 Vermillion

Vermillion is also known by the names cinnabar and China red, but you definitely don’t want to be mixing up any of it at home. Vermillion gets its red-orange hue from mercury, and the smaller the mercury particles are, the brighter red vermillion is. It has been used for close to 8,000 years, since Ancient Romans retrieved it from Spain and used it in cosmetics and art. It was also used to illuminate medieval manuscripts. Prisoners and slaves were given the dangerous job of mining cinnabar in the Spanish mines of Almadén, and it was then heated and crushed to form pigment.[12] It was also used in Renaissance painting and of course in China where it got its alternate name. There it was mixed with tree sap and used for temples, ink, and pottery.[13] The Ancient Chinese created synthetic cinnabar, but it was still toxic. Eventually Cadmium red replaced it as the choice for artists in the 20th century, as it was much less deadly and didn’t fade into a reddish-brown, as vermillion had the tendency to do.[14] Bright red-orange remains associated with traditional Chinese culture to this day, associated with luck and happiness.

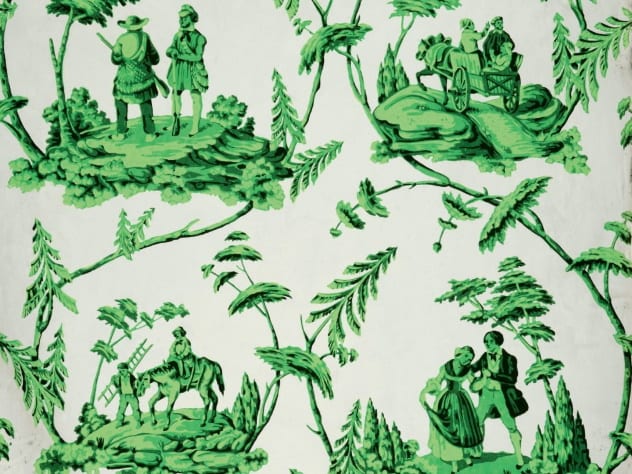

6 Scheele’s green

In the early 1800s, a brand new dye swept the Victorian high society. German color-maker Carl Wilhelm Scheele released a shade of green so vibrant that it became the go-to of ladies attending parties across Western Europe. New gas lamp technology made nighttime events brighter and this emerald green was perfect to make a statement as a modern and fashionable woman. Soon Sheele’s green was seen across Britain in dresses, wallpaper, carpeting, and artificial plants. Unfortunately, this new dye color was made with copper arsenite, which contained the deadly element arsenic. Women who wore it broke out in blisters. Families started vomiting in their green living rooms. The factory workers who used the dye daily suffered organ failure. One faux flower maker named Matilda Scheurer suffered a gruesome death, throwing up green, the whites of her eyes turning green, and telling others that everything she saw was green.[15] Although people at the time were aware that arsenic was deadly when ingested, the buzz around Sheele’s green helped to spread the idea that the material could kill through other methods of exposure as well.[16] Despite doctors and media quickly figuring out the connection, people resisted the warnings in the name of fashion until 1895.[17] 10 Explanations For The Color Schemes Used On Everyday Things

5 Lead white

As far back as the 4th century B.C., the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians were using this thick white pigment for make-up, medicine, and paint. Ancient Greek authors Pliny and Vestruvious even described it in their writings.[18] The process for making it was fairly simple: soak lead metal in vinegar and then scrape off the white powder that formed. Many manufacturers and artists developed what was called “Painter’s Colic”, which we now recognize as lead poisoning.[19] Lead white’s thick consistency and fast drying speed made it a favorite of artists across Europe. But lead can enter the body if it is breathed in, ingested, or absorbed and it can cause long-term damage to the brain and kidney.[20] Even though it was clear that this paint was deadly, artists couldn’t find a good match for its creamy warm tones, and it was used until it was formally banned in the 1970s.

4 Uranium orange

In 1936, the Fiestaware ceramics company started to come out with a bright new line of dinnerware. A bold orange-red color called “Fiesta Red”, these dishes started appearing in homes across America. The bright color came from uranium oxide, which is radioactive. From 1943 to 1959, the production of these orange dishes paused, as uranium was banned from civilian use to save it for the war effort. When they started production again, a different form of uranium was used, called depleted uranium, which is slightly less radioactive than the natural form.[21] Many dishes from the time period used radioactive materials in their production, and the EPA warns that they can now emit alpha, beta, and gamma radiation.[22] Fiesta red dishes were produced until 1972, when the line was discontinued, but this line is still highly sought after by collectors, although it is recommended that you don’t actually eat off them, especially acidic food.[23] Fiestaware still makes dinnerware, although the colors will not match the old ones due to the fact that they no longer use uranium or lead in their glazes.

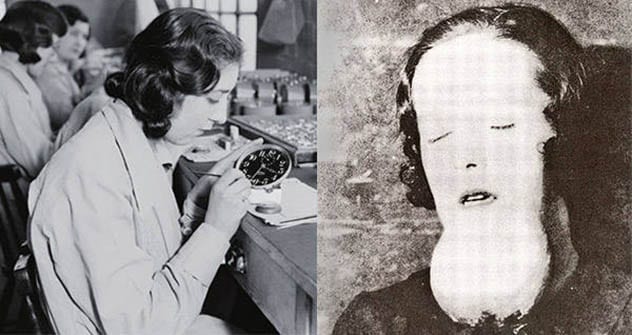

3 Radium green

In 1908, a very unique paint appeared. It was self-luminous and glowed a bright green in the dark, which was perfect for watches and compasses that could now be used at night. Radium appeared all over the market in the late 1800s to early 1900s, used in drinks, candy, creams and lotions, soap, spas, and swimming pools. The glowing, fizzling radium became connected with the idea of a healthy glow.[24] The watches were first used for the military in World War I, and after the war, they began to spread to consumers. A group of young women and girls worked in the factories painting watch faces, later known as “the Radium Girls”, and it was considered an artistic job with access to this fun, newly discovered substance. The girls licked their paint brushes to give them a fine point and also sprinkled the dye on their fair and face so they would glow in the dark at parties. In the 1920s, the girls started to show signs of radiation poisoning. They developed sores, rotted jaws and teeth, and several died before the problem started to be understood. In 1928, Grace Fryer led her fellow workers in suing the New Jersey factory, causing a media frenzy. The girls won.[25] Many of the surviving girls also agreed to be studied in the 1950s, and the U.S. vastly expanded their understanding of the effects of radium on the body. Radium paint for watches officially stopped being used in 1968. Glow-in-the-dark products today are most often made with photoluminesce, where they absorb and then re-emit light, which is not toxic.[26]

2 Red-green and blue-yellow

These two colors are not forbidden by any ruler or made of some deadly material. The problem with these colors is that they are almost impossible to see. Red and green cancel each other out inside of the human eye and blue and yellow do as well. The retinas of the human eye allow us to take incoming light and make specific neuron fire in the brain to recognize each color. But these pairs of colors inhibit each other in the brain, so they cannot be viewed simultaneously. Until 1983, when scientists Hewitt Crane and Thomas Piantanida conducted an experiment. Volunteers were shown adjacent stripes of yellow/blue or red/green. Each eye was forced to focus on a single color using an eye tracker. By doing this, their eyes were tricked into slowly blending the colors and creating a new shade.[27] Participants reportedly had trouble describing this, as no words existed for these colors. When a repeat study was done in 2006 by Dartmouth University and scientist Po-Jang Hsieh, volunteers were given a color mapper to try and match the impossible colors that they saw, and some chose a brownish color referred to as “mud” for the red-green combination.[28]

1 Gamboge yellow

In the 1600s, the British East India Company brought back a new bright yellow pigment from Asia. Gamboge was named after the country of Cambodia, which used to be called “Camoboja” from the Latin word “gambogium” meaning pigment. It was collected as sap from bamboo shoots of trees at least ten years and then turned into fine powder or hard rocks that could be wet to paint with. This sap was poisonous itself, but that was not the only reason that gamboge became unpopular. The color was used in traditional Chinese painting, but the color faded fast and can be hard to recognize today.[29] In the mid-1800s in England, a snake oil salesman named James Morrison came out with “Morrison’s vegetable pills” made of gamboge, which acted as a strong diuretic and laxative. Doctors quickly realized that gamboge irritated the skin and could be deadly as medicine in even small amounts. Also in 1980s, a Winsor & Newton paint company employee found a bullet in a piece of gamboge, and it was quickly discovered that it had been collected from the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge.[30] In 2005, Winsor & Newton stopped using Gamboge and replaced it with a non-toxic version called “New Gamboge”.[31] 10 Moments That Changed Color Forever