For those of you with a fear of flying, it is worth noting that seven of these ten items (bonus excluded) occurred in the ’70s and ’80s, and two of the three more recent accidents occurred in countries that people would think twice about visiting. Deadly accidents reveal shortcomings and ultimately make air travel safer.

Location: Near Moneron Island, Soviet Union Fatalities: 269 Survivors: 0 The first item on this list is one of the most complicated to explain and had the potential to be one of the deadliest accidents in history: this classifies as one of the tensest moments of the Cold War. Due to incorrect use of navigation systems, a flight from Anchorage to Seoul deviated slightly to the north, not long after takeoff, and continued on an incorrect route towards the Soviet Union for five and a half hours. Various things should have indicated the deviation, including the fact that it was out of range of normal communication with Anchorage and had to relay reports through another flight that should have been very near to them; however, cockpit recordings make it clear that the crew had no idea that they were in any danger at all. The plane happened to be flying towards the Soviet Union in a time when relations between the two superpowers was certainly not at their best and, furthermore, on a day when a Soviet missile test was scheduled. The Korean flight crossed over a peninsula in the Soviet Union, re-entered international airspace, and then entered Soviet airspace for a second time. Because of the test, there was also an American military plane in the area, and the two planes passed so close to each other that the Soviets were not sure which was which. One of the Soviet Air Defense commanders decided that, having flown into Soviet airspace, the plane must not be a civilian plane. Unaware of the danger, the pilots decided to climb to a higher altitude, which slowed their airspeed in what appeared to be an evasive maneuver to the fighter pilot following them. The Soviet pilot shot the plane down just as was crossing back to international airspace once more. The Soviet Union initially denied any knowledge of the plane, then fabricated observations about the plane so military commanders could claim that it had not appeared to be a civilian aircraft. They accused the United States of having sent the plane to spy on them and even of attempting to incite war. During search-and-rescue, American and Soviet teams did their best to obstruct each other, and even after the plane’s black boxes were released after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there is still some controversy and plenty of conspiracy theories concerning this plane.

Location: O’Hare Airport, Des Plaines, USA Fatalities: 273, including 2 ground fatalities Survivors: 0 The deadliest airline accident on US soil occurred in a DC-10, a model that has earned itself a very bad safety reputation, despite being generally a safe plane. The last maintenance on this particular aircraft, eight weeks before the disaster, had damaged the pylons attaching one of the engines to the plane. As the airplane began its takeoff from O’Hare, that engine broke off from the aircraft and fell back onto the runway, taking a large section of the left wing with it, cutting electrical systems, and spilling hydraulic fluid, which controlled some mobile parts of the wing. The pilots, unable to see the wings and unaware that they were losing fluid and therefore control, attempted to keep themselves in the air and perform the proper procedure for engine failure during takeoff. However, the damaged left wing stalled, and the airplane rolled into a dive and crashed into an open field. Debris was thrown into a nearby trailer park, destroying several trailers and cars and an old aircraft hanger, as well as severely injuring several people on the ground and killing two. Everyone onboard was killed by the impact or resulting fuel fire. The entire DC-10 fleet was temporarily grounded while investigators determined which other planes had also been damaged by these incorrect maintenance procedures.

Location: Persian Gulf Fatalities: 290 Survivors: 0 In another, somewhat similar, controversial military incident, an Iranian Airbus was shot down over the Persian Gulf during the Iran-Iraq war. Shortly after a confrontation in international waters between the United States military helicopter USS Vincennes and Iranian gunboats, the Vincennes saw what appeared to them to be an Iranian F-14A Tomcat fighter flying towards them. The Navy hailed the airplane seven times on a military frequency, which it could not pick up, then three times on a civilian frequency. The crew of the Airbus may have thought these three calls were directed towards another Iranian aircraft, that one a military surveillance airplane, that had recently been in the area. As the airbus appeared to dive towards them, the Vincennes finally fired two missiles that both hit the airbus. Iran does not believe this was an accident and insists that, even if it was, it was caused by recklessness and is therefore an international crime. One explanation for the accident is a psychological expectation to see a fighter plane after the gunboat battle and then to see it dive to attack; there were also confusion with the transponder codes that made it temporarily appear to be broadcasting a military code. The United States has never formally apologized for the accident.

Location: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo Fatalities: possibly 2 onboard, between 225 and 348 on the ground Survivors: possibly 5 onboard This is by far the deadliest airplane accident for people on the ground. There is not a lot of information about this crash, probably because of its location and illegality. This cargo aircraft was leased from Russia, but it was being flown out of license. It was overloaded, possibly carrying weapons to an Angolan military group and fully fueled. It did not reach the proper speed for takeoff, but attempted to lift, anyway. The plane crashed into a nearby marketplace, then exploded in a fireball, killing somewhere between 225 and 348 people, and injuring about 500 more. It’s not clear that anything has been learned from this accident (the 2007 Africa One crash is said to be a “virtual repeat” but with only 51 deaths).

Location: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Fatalities: 301 Survivors: 0 Six minutes after Saudia 163 took off from Riyadh, warnings sounded about smoke in the cargo compartment. The crew spent another four minutes trying to figure out what to do, then finally turned back to the airport. Damage from the fire forced them to shut down their middle engine. The airplane landed safely but not quickly — it continued to roll down the runway, away from the emergency vehicles that had expected them to stop immediately, and then the crew failed to immediately order an evacuation. Most people died of smoke inhalation during the beginning of the evacuation. The doors were not opened by rescue workers until fifteen minutes after the landing. The source of the fire is still unknown, but after this disaster, the airline improved emergency procedures and crew training and the manufacturer removed potentially flammable insulation from the cargo bay.

Location: near Kerman, Iran Fatalities: 302 Survivors: 0 This accident has even less information about it than the Air Africa crash, which is absolutely ridiculous considering the number of people that died. It is known that there were high winds and fog the day of the crash, so bad weather is considered the most likely cause. Terrorist action, mechanical problems, and a mid-air collision (Surely we’d know of another plane, then?) have also been suggested as causes. Most of the passengers belonged to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Location: Ermenonville, near Senlis, France Fatalities: 346 Survivors: 0 Watch this video on YouTube This is the deadliest crash of a DC-10, probably creating its terrible reputation, and was the deadliest accident in any plane at the time. Flying from Paris to London, the plane had an unusually large number of people onboard for this flight because of a British strike. As they flew over the town of Meaux, France, there was the sound of a muffled explosion and loud rush of air as the cargo hatch blew off. The cabin floor above the cargo hold collapsed, destroying the lines that connected the flight controls to the actual parts they were controlling. The pilots fought for control for 72 seconds before the aircraft crashed into a forest. The airplane disintegrated to such an extent that a bomb was temporarily considered as a possible cause. The cargo hatch that had blown off was found in a field along with part of the cabin floor and six seats still holding their dead passengers. The cargo hatch of the DC-10 opens outward, dangerous on any airplane, where air pressure pushes outward. It was already known that the locking mechanism was potentially faulty. Changes had been made after a near-deadly accident two years before, but those changes were neglected on this particular aircraft, and the engineers did not properly check the cargo door. The cargo door problem on the DC-10 was finally fixed after this disaster, but the entire 747 fleet was grounded fifteen years later for a very similar problem.

Location: Charkhi Dadri, India Fatalities: 349 Survivors: 0 In November, 1996, a Kazakhstan Airlines modified military plane flying flight KZK 1907, carrying 27 passengers and 10 crew, was descending to land at a Delhi airport. The cockpit crew had limited English, and they relied upon a radio operator to speak to Air Traffic Control, creating a greater risk for mistakes. The plane was cleared to descend to 4600 feet, but the Kazakhstan’s radio operator had failed to inform the crew that they had to stay at that altitude, and they continued descending. Meanwhile, a Saudi Arabian Airlines Boeing 747 carrying 312 people, SVA 763, took off from Delhi flying directly towards them and was cleared to 4300 feet. The Kazakhstani flight was descending through 4300 feet, and it would actually have passed under the Saudi Arabian jet, but just then the radio operator remembered to convey the message that they should remain at 4600 feet. They began to climb again, and the planes saw each other too late. The tail of the Kazakhstani plane cut through the Boeing’s wing. The Boeing lost control, broke up, and crashed, killing everyone onboard. The Kazakhstani plane soon crash-landed. Four people were rescued, but all were critically injured and died soon later. The Delhi airport used a radar system that showed only approximate locations of each plane, which was outdated long before the ’90s. They also only had one air corridor open for civilian traffic, meaning that takeoffs and landings use the same airspace. Investigators recommended several changes to the airport, and the national aviation authorities made it mandatory for all flights in and out of India to be equipped with a Traffic Collision Avoidance System.

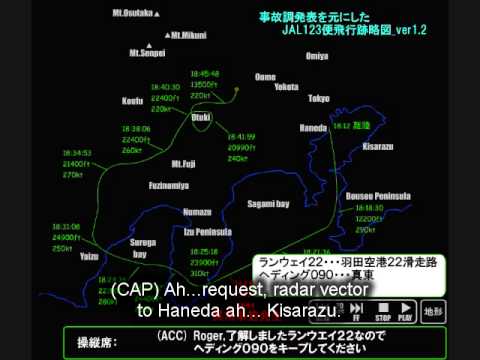

Location: Ueno, Japan Fatalities: 520 Survivors: 4 Japan Airlines Flight 123 was, by a margin of almost 200 people, the deadliest single-aircraft crash in history. The flight was during a very busy time of year, in a very busy year, for Japan Airlines, and although it was only a domestic flight, the plane was packed. 12 minutes after the flight took off, the rear bulkhead (the area between the cabin and the tail) failed, tearing off the rudder and simultaneously destroying all four hydraulic systems, essentially eliminating all of the pilot’s control over the plane. In this situation, the only method of controlling the plane is through differential engine thrust: using engines on one side more than the other will cause the plane to turn. However, this only allows very limited control. The crew tried return to Tokyo, then to land at an American military base, but the plane continued to wander. Finally, it began to descend into the mountains and crashed around 7 pm. A search-and-rescue crew from the American base located the plane only twenty minutes after the crash, but the Japanese authorities asked them to keep away from the site. A Japanese helicopter found the wreckage during the night but, in the darkness and on a mountainside, was unable to land. It reported that there were no signs of survivors, so the rescue workers decided to wait for daylight. Only four people survived the night, all from the same area of the plane. It is unknown how many people survived the initial impact. The cause of the crash was traced back to a tailstrike during a landing seven years before, which badly scratched the bottom of the plane. The damaged area was patched incorrectly, using two different patches to cover the area and not adding all three rows of rivets required. The repair could not possibly survive so many flights and finally failed.

Location: Tenerife Airport, Canary Islands Fatalities: 583 Survivors: 61 Fortunately for us, the deadliest airplane accident in history is the sort of thing that could never happen twice. It’s amazing enough that this happened even once, and it stands as proof that a great number of things usually have to go wrong before a disaster can occur. After a terrorist bombing at Gran Canaria (Las Palmas) International Airport, five large aircraft and a number of small aircraft that had been scheduled to stop there were diverted to the Los Rodeos Airport on Tenerife. Los Rodeos was a much smaller airport, with one runway with a parallel taxiway and four exits between them. Planes usually taxied up the taxiway, then turned onto the runway and took off. In these extremely cramped conditions however, the parked aircraft took up a significant amount of the taxiway, meaning that a plane had to taxi up the runway and then somehow turn around to take off. Two 747s waiting at Los Rodeos were Pan Am 1736 and KLM (a Dutch airline) 4805. As soon as the Gran Canaria airport reopened, the Pan Am was ready to leave. However, the captain of the KLM had decided to refuel at Los Rodeos, apparently to save time since he was in a hurry to get home, and the plane was blocking the Pan Am from getting onto the runway. Refueling both kept the Pan Am behind the KLM and made time for a heavy fog to set in. When it was finally ready, the KLM was told to taxi up the runway and turn 180 degrees to prepare to take off. The Pan Am was told to taxi up to the third exit, cross back to the taxiway (clear at that point of other airplanes), then turn back onto the runway after the KLM left. However, the crew of the Pan Am was confused about which exit to take, particularly since they were not marked by number and visibility was low in the fog. Also, the slant of the exits meant that the third exit would require performing two 135 degree turns, nearly impossible in that amount of space, while the fourth exit would require two comfortable 45 degree turns. The Pan Am continued taxiing to the fourth exit. The captain of the KLM (an arrogant and difficult-to-work-with man who spent most of his time training new pilots, including his flight engineer on this flight, or talking to the media rather than flying) began to prepare for takeoff. His flight engineer pointed out that they did not have clearance to leave. They asked the controller for clearance, but the answer was unclear, partly due to interference from the Pan Am radioing at the same time to point out that they were still on the runway. The flight engineer did not dare point out a second time that they did not have proper clearance, potentially embarrassing the captain. The fog meant that neither plane could see the other, the local air traffic controller could hardly see the two planes, and the crew of the Pan Am most likely believed that nobody would be allowed to take off in such low visibility. The KLM began to take off down the runway. They came in view of the Pan Am just as the Pan Am reached the fourth exit. The Pan Am pilot took a hard left onto the exit, and the KLM pilot hurriedly attempted to take off. Because of their enormous weight, being full of fuel, and their steep takeoff angle, their tail scraped along the runway, and the bottom of the KLM and its landing gear hit the upper right side of the Pan Am, tearing the top off. The KLM plane was momentarily airborne, but it had lost use of two of its engines, and it crashed back onto the runway. The enormous fuel fire killed everyone on board. 61 people on the Pan Am, including the flight engineer, ultimately survived. Conversations with air traffic control became much more standardized, avoiding confusion such as whether the KLM had clearance to take off, after this accident. Crew resource management, considering the crew to be a team and downplaying the importance of the captain, has also been emphasized to avoid situations like that of the KLM cockpit.

Location: in the air near Yaizu, Shizuoka, Japan Fatalities: 0 (99 injuries) Survivors: 677 If you know of a near miss involving more people than this one, please add it in the comments. Early in 2001, at about the time that the flight attendants began to serve drinks aboard Japan Airlines 907, a Boeing 747, the plane’s Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) began to go off. Another, Japan Airlines plane, Flight 958, this one a slightly smaller DC-10, was flying towards them at about the same altitude. An Air Traffic Controller noticed that they were on a potential collision course; however, Flight 907 descended as he ordered while 958 chose to descend as their TCAS was ordering. A trainee Air Traffic Controller then tried to tell 958 to descend but spoke to 907 instead. His supervisor then tried to tell 907 to ascend, but he accidentally referred to Flight 957, which did not exist. At the last moment, with the DC-10 so close that almost nothing else could be seen outside his windshield, the pilot of the Boeing executed a violent dive to avoid collision, injuring 99 people onboard. The two planes came within 100 feet of each other. Had the pilot moved any slower, it is almost certain that everyone onboard both planes would have been killed, making it the deadliest airline accident ever. No action was taken to make the skies safer until after the deadly Überlingen collision the next year. In the airline industry, people have to die before change is made.