SEE ALSO: 10 Lesser Known Massacres

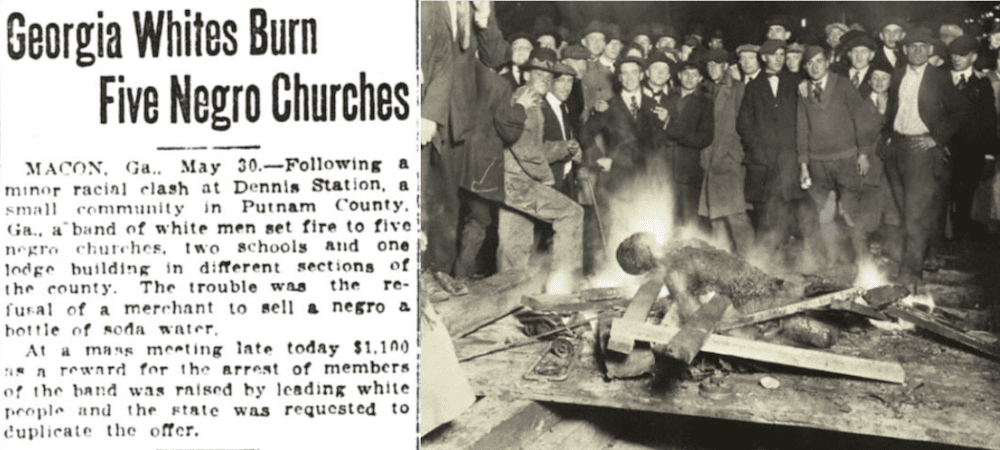

10 Rosewood Massacre

A small, overwhelmingly black town in Florida, Rosewood was essentially completely destroyed in January of 1923. In the nearby town of Sumner, a 22-year-old white woman named Fannie Taylor was heard screaming and, when her neighbor came to check on her, she was covered in bruises. Claiming to have been assaulted by a black man , she reported that she had not been raped, though the other white citizens in her town believed otherwise. Her husband gathered a group of Sumner residents and began searching the area for a black prisoner who was said to have escaped a nearby chain gang. Additionally, around 500 members of the KKK were in the area and they joined the mob which eventually decided the town of Rosewood was hiding the target of their ire. Eventually, they reached the town and began terrorizing those they suspected of aiding the escaped prisoner, beating, torturing and even killing some of them. After some white people were killed by those defending themselves, the choice was made to burn the town to the ground. In all, anywhere from 6 to 27 black people were killed, with the rest escaping with their lives but none of their possessions, as many of them refused to return to the area, fearful of more violence.[1]

9 Atlanta Race Riot

Fearful of the growing power of the black citizens of Atlanta, the white elites in the city began using the local newspapers to push their racially motivated opinions. The governor’s race of 1906 was especially repugnant, as various newspapermen utilized their positions to help their campaigns by spreading false information about the state of race relations in Atlanta. A favorite of theirs: any lurid tale of a “pure” white woman being assaulted by a black man. No one particular story sparked this riot but tensions rose to a breaking point on September 22nd. Eventually, white mobs began terrorizing majority-black neighborhoods, setting fire to any black business they could find and beating and shooting those unlucky enough to cross their path. By the time a heavy rain dispersed most of the crowds, the state militia had showed up and restored order. However, small pockets of violence remained for the next two days and, in the end, as many as 40 African-Americans lost their lives.[2]

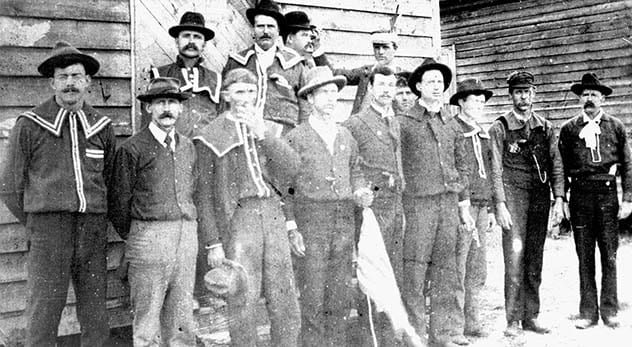

8 Thibodaux Massacre

Less than two decades after slavery was outlawed in the United States, many African-Americans working in the South began to realize the power their labor represented. This led to an increasing number of strikes, especially amongst sugar workers. In 1887, some sugar workers reached out to the Knights of Labor, the biggest union of them all. With the help of organized labor, the black workers soon began to demand appropriate wages. Instead of negotiating, the plant owners began firing union members. When strikes began, they also hired strike-breakers and created militias, armed to the teeth and out for blood. On November 23rd, a mob of white men dragged a number of black workers from their houses and led them to the railroads. Once they arrived, the men were told to run for their lives, before they were all shot in the back by the armed mob. By the time the violence died down, at least 35 people had died. Defeated and cowed, the workers all went back to the plantations and not one person faced justice; in fact, one of the murderers even won a seat in Congress the following year.[3]

7 Ocoee Massacre

Colloquially known as a “sundown town”, a phrase which was used to illustrate to the black visitors to the city they were not welcome once night fell, Ocoee, Florida was once the site of a horrific amount of violence. For nearly a year, voting rights activists had been encouraging the black citizens of the state to exercise their right to vote and many of the white citizens began to see it as an attack on their supremacy. On November 2, 1920, a relatively wealthy African-American man named Mose Norman tried to vote but was turned away. Members of the KKK even took a gun away from him, a weapon he had brought to protect himself, and ordered him to go home. Later that day, a mob of whites, many of them KKK members, traversed the black neighborhoods looking for Norman before eventually deciding to head to the home of another prominent black man: July Perry. Eventually, they captured him, lynched him and burned his neighborhood down. The terror wrought by the mob was so great that Ocoee turned into an all-white town for decades. During the 1920 census, around 500 black people called Ocoee home; in 1940, 1950, 1960 and 1970, every census taken revealed there to be no black citizens at all.[4]

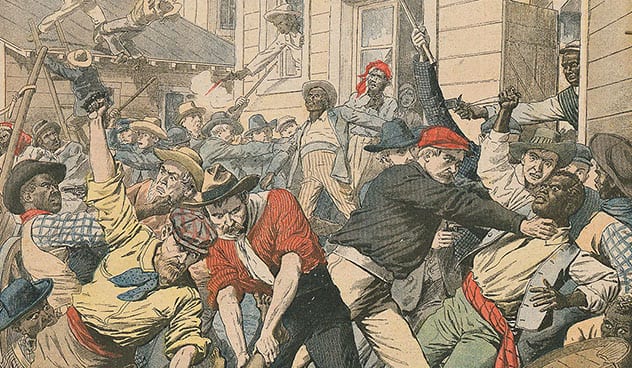

6 New Orleans Massacre of 1866

Only one year after the Civil War ended, Republicans in the state of Louisiana were looking to give newly freed black men the right to vote. In fact, they went so far as to call a convention, trying to get it enshrined in the state constitution. The main reason for this was that the white voters, many of them Democratic Confederate veterans, were constantly passing racist laws, laws which would essentially reduce the black citizens of the state to a status akin to slavery. On July 30, 1866, the convention commenced, with hundreds of Confederate veterans serving as “emergency police officers” and dozens of black men, many of them Union veterans, marching through the streets in support of the proposed changes. As tension continued to grow between the two groups, a shot rang out. Armed to the teeth and better prepared for violence than their counterparts, the white mob began attacking the black marchers. Lucien Jean Pierre Capla, a witness to the violence, later recalled: “I saw the people fall like flies.” (Capla and his son were both brutally attacked, suffering incredible wounds.) When federal troops finally showed up, more than forty black men were dead, with over a hundred wounded from the fighting.[5]

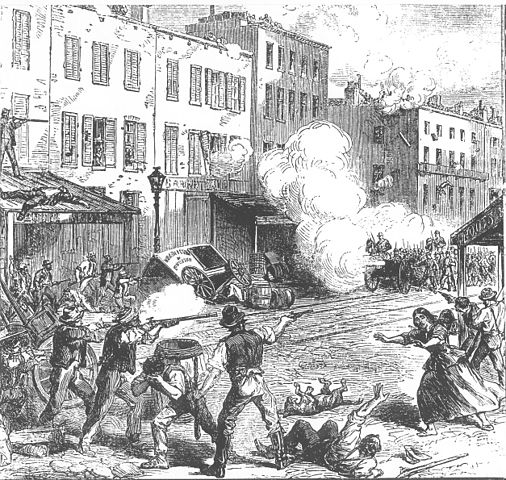

5 New York City Draft Riots

As indicated by the name, the New York City draft riots of 1863 originally began as a violent opposition to a new federal conscription law which greatly increased the number of men who faced being called into the war. Two other factors also angered much of the citizenry: it was possible to pay for a substitute, though it was only available to the very wealthy, and African-Americans were exempt, as they were not considered citizens. Like much of the racially motivated violence of the times, the anger of the working-class whites was inflamed by newspapers, publications which ran stories warning of a flood of newly freed men flooding the North with workers willing to undercut the pay of the whites of the area. So it went, on July 13, 1863, that the white mobs, initially only attacking federal buildings, would eventually turn their ire to the black working-class citizens of Manhattan. Over the course of four days, hundreds of black residents were forced from their homes and over 100 were killed, many of them lynched in the sort of violence usually reserved for the South.[6]

4 The Red Summer

Less an isolated incident and more a collection of similarly-themed violence, the Red Summer took place in 1919, as numerous African-Americans adjusted to civilian life after having returned home from WWI, alongside their fellow white veterans. Famed civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois said of the black veterans: “we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.” Faced with men who were no longer willing to live under Jim Crow laws, many whites began to assault random black men throughout the country, especially those who had fought in the war. Though much of the violence occurred in the North, as the Great Migration dramatically changed the demographics of a number of major cities, the largest instance of violence occurred in the small town of Elaine, Arkansas. For three days, unspeakable violence was meted out to black sharecroppers who were trying to improve their working conditions; over 200 men, women and children were murdered because of it.[7]

3 Opelousas Massacre

For the white Democrats in Louisiana, 1868 was a tough year. Thanks to the votes of recently freed black men, Republicans won a vast majority of the elections that year. Faced with the prospect of losing their stranglehold on local and state politics, many racists, especially those in the Knights of the White Camellia (a pre-cursor to the KKK formed to stop Republican successes at the polls through intimidation) began violently oppressing all the black people they could get their hands on. Similar to the KKK, the Knights of the White Camelia was a white supremacist terrorist organization and they were extremely popular in the St. Landry Parish. (One Democratic newspaper estimated nearly one in four white people were members of the group.) On September 28, 1868, as the U.S. Presidential election was beginning to inch closer, a local newspaper editor was beaten. Around a dozen black men came to his aid and they were subsequently arrested; however, they were later dragged out of jail and lynched. This was just the start of the violence that night: armed white people began scouring the countryside for every black person they could find and murdering them as soon as they did. By the time the violence subsided a few weeks later, somewhere between 200 and 300 African-Americans were killed. Republican Ulysses Grant won the presidency against the anti-black Democratic contenders Horatio Seymour and Francis Blair.[8]

2 Wilmington Insurrection of 1898

The site of the only coup d’état to take place on American soil, Wilmington, North Carolina was a hotbed of racial tensions in 1898. Having lost control of the state in 1894, the state’s Democrats changed their tactics, relying on an explicitly racist campaign platform, centered on the scourge of black men preying on innocent white women. However, the city council of Wilmington ended up being interracial, perhaps as a rebuff to the white supremacists. Unwilling to face the changing face of their city, nearly 2,000 white men launched an attack. First, they burned a local newspaper, The Daily Record, to the ground. Next, they marched through the city, exiling black citizens and killing those unwilling to leave, murdering as many as 60 people. Finally, they forced the duly elected local government to resign at gunpoint, installing their own leadership who, only days prior, had promised to “choke the current of the Cape Fear River” with black bodies.[9]

1 Tulsa Race Riot

Unlike some of the incidents on this list, the Tulsa Race Riot can be traced to one specific incident: on May 30, 1921, a 19-year-old black man named Dick Rowland was accused of attacking a 17-year-old white elevator operator named Sarah Page. He was quickly arrested and the local police began an investigation. However, newspapers fanned the flames of racial violence by publishing more and more lurid reports about Rowland’s actions. Two separate mobs, one black and one white, descended on the courthouse, determined to either protect or kill Rowland, respectively. Outnumbered, the black mob headed back to the Greenwood district, an area known as Black Wall Street because of the concentration of black businesses. Out for blood, as many as 10,000 white people crossed the railroad tracks in pursuit of the fleeing African-Americans. As dawn broke, nearly 35 whole city blocks had been burned to the ground and at least 300 black people had been killed. In an especially violent twist, Tulsa was likely the first American city to be bombed from the air as at least one local company was said to have allowed the white mob to use their planes to drop burning turpentine balls from the skies.[10]