10The Bonfire Of The Vanities

In 1494, the Medici family were temporarily chased from Florence, Italy, and into their place stepped Girolamo Savonarola. A Dominican friar, Savonarola took it upon himself to become the city’s moral compass and cleanse it of all its corrupt art and literature. And there was a lot of it—Savonarola and his followers cracked down on everything from paintings by the great masters to carnivals, gambling, and poetry. They even denounced seemingly harmless things like jewelry and nice clothes. By 1497, he had a network of street urchin spies that were reporting back to him on all the morally questionable things they saw going on in their city. Things were so bad that he apparently saw no choice but to organize the Bonfire of the Vanities and burn everything that he thought was inappropriate. That included everything from gambling tables and fine clothes to carnival masks and books he deemed indecent. Among the works thrown onto the bonfires in the streets of Florence were manuscripts and paintings, including works by Botticelli. Some accounts say that Botticelli himself helped pitch his works onto the fire, deeming his own depictions of religious imagery too racy to be respectful. Images of the Virgin Mary were too like his pagan images of figures like Venus. Works of Michelangelo were also said to be torched on the bonfires. Florence’s tolerance for the mad monk’s crusade against everything fun didn’t last too much longer. On Palm Sunday in 1498, Savonarola was arrested, tortured, and then put on a bonfire of his own.

9Lisbon’s 1755 Earthquake

At about 9:40 AM on November 1, 1755, a massive earthquake struck the center of Lisbon, Portugal. Estimates of casualties go all the way to 70,000 people. The quake wiped out the city center and made huge sections of the city completely uninhabitable. After the earthquake and aftershocks stopped, fires broke out across the city and burned for more than a week. The two main city squares were completely destroyed, along with the waterfront districts, which were engulfed by a tidal wave. The Opera House, the City Hall, and the Royal Palace—along with all the surrounding buildings—were destroyed. Fire ate almost all of the city records, along with the palace of the Marques of Lourical; that palace alone contained 18,000 books and 1,000 manuscripts (including a historical document handwritten by Emperor Charles V), more than 200 works of art (including pieces by Rubens, Titian, and Correggio), and a massive collection of documents pertaining to the age of exploration. Estimates on the losses of the city are staggering. According to one document, Lisbon lost about 87 percent of its churches, 86 percent of its convents and other religious buildings, 17,000 homes, 53 royal palaces, and almost 2 percent of its annual gross domestic product in diamonds alone.

8The Calvinist Iconoclasm

Starting in the mid-1500s, Christianity split between the up-and-coming Calvinism movement and other Christian traditions. At the forefront of the debate between the two groups was the use of images in religion. According to the popular view of church fathers like Erasmus, there was far too much nudity and the like in religious artwork and sculpture, and there was also a massive amount of rather questionable behavior going on in the presence of these works. He—and others—believed that the creation of art and relics was being done simply for business reasons and gain. Throughout the century, there were regular occurrences of iconoclasm—whose original, literal meaning refers to the physical destruction of religious imagery. It happened in a large part in the Netherlands but also in Britain, France, and Germany. Supporters of the movement saw little difference between the presence of religious artwork and the worship of idols. By 1566, iconoclastic sermons attracted such massive crowds that they needed armed guards. The Netherlands became a hotbed of activity. After sermons, supporters stormed churches, convents, and monasteries and destroyed religious artwork in massive amounts. Among the works targeted by the movement was the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, better known as the Ghent Altarpiece and perhaps even better known as one of the major works stolen by the Nazis and recovered by the Monuments Men. In 1566, the altarpiece was removed from its church and hidden first in a church tower and later in a town hall, protected by caretakers who feared it was going to be destroyed by the movement. It remained hidden for two decades until it was returned to display.

7The Sacking Of Nalanda University

Nalanda University was founded in 427. Until its destruction in 1197, it was one of the great repositories of knowledge in the Buddhist world. At its height, the university taught 10,000 students at a time. It had a nine-story library with numerous works on everything from Buddhist doctrine to economics, astronomy, the arts, science, politics, and military tactics. Everything about the university was on a wide scale—students came to the northern Indian university from as far away as Japan, Persia, and Turkey. The university—and its extensive library—was sacked with the order of a Turkic general in 1193. It’s said that the destruction of the campus and its treasures happened all because they didn’t have a copy of the Quran in their library, and the general took it as a slight. There were so many books and manuscripts—many of which had been painstakingly copied to ensure that the resident scholars had their own versions of the texts—that the library continued to burn for several months after the sacking had started. In the 1990s, a movement began to bring back the university and restore it to its former glory.

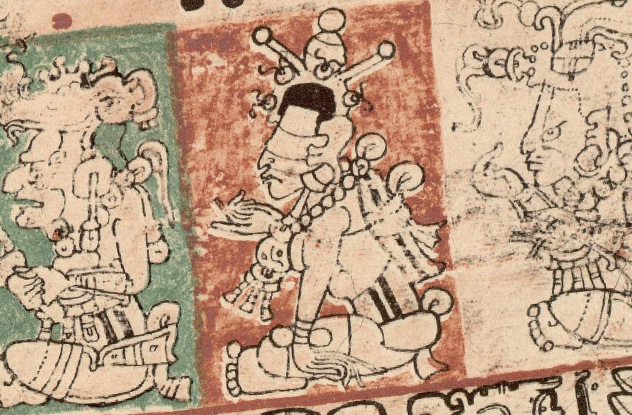

6The Burning Of The Mayan Codices

The Maya are one of the most enigmatic of all ancient civilizations, and that is in part thanks to the interference of the Spanish conquistadors who first contacted them in the 16th century. The Maya’s elaborate system of writing included symbols that stood for words and sounds. When the Spanish originally made contact with the civilization, at the head of the party was Catholic friar Diego de Landa. Landa had joined the voyage to get the Mayan people to turn their backs on their native religion (and their human sacrifice) and convert to Catholicism. He decided that the way to do that was to burn their history. Landa oversaw the burning of Mayan codices, along with the destruction of religious idols, art, texts, writing, and imagery that at all related to the Mayan mythology and especially to the practice of human sacrifice. When all his destruction went in vain, and the people continued in their old ways, he turned to torture and imprisonment. When this brought the ire of the church down on him, he wrote his book on what he’d learned from the Mayan civilization. Of all of the written codices of the Maya, only three survive today. They were given the names of the European cities they were taken to—Paris, Madrid, and Dresden—and include some amazing information about the Mayan methods for predicting solar and lunar events, the movements of the stars, and information on ritual practices.

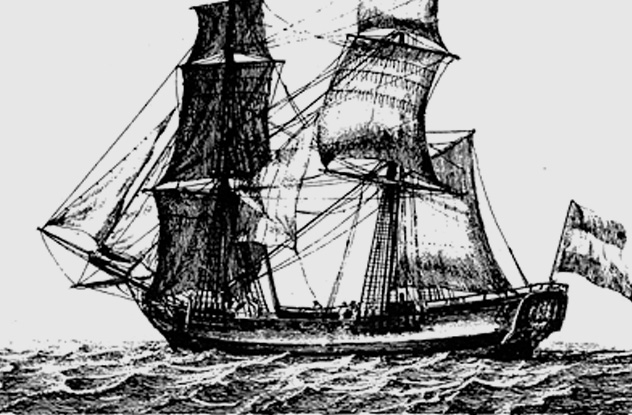

5The Wreck Of The Vrouw Maria

The Vrouw Maria was a Dutch merchant ship loaded with luxury goods and bound for Russia when it sank off the coast of Finland in 1771. Aboard the ship was a variety of generic merchandise like textiles and cloth, ivory, and coffee. Also on board was a collection of paintings recently acquired by Russian ruler Catherine the Great at auction to elevate Russia’s cultural status. It’s been difficult to tell just what they managed to buy. The auction took place in the middle of a period when Catherine was buying up all the art she could, and it’s thought that some of the works included pieces by Gerard Dou, along with works from 17th-century Dutch masters like Jan van Goyen, Adriaen Storck, and Philips Wouwerman. Catherine’s agent at the auction was another member of the nobility, Prince Gallitzin. The prince was buying paintings not just for Catherine but also for himself and other noble clients. It’s thought that some of the paintings were rescued from the sinking ship, but even a close examination of the logs from the auction haven’t revealed just which masters’ works ended up at the bottom of the ocean.

4The Arno River Flood

In 1966, the Arno River rose and rose throughout the rainy season, breaching its banks in November and submerging the city center of Florence, Italy beneath around 70 billion liters (18 billion gal) of water. With no warning and no time to prepare the city for the impending day-long flood, the results were catastrophic. More than 20,000 people were suddenly homeless, 39 were dead, and the city’s cultural heritage was muck-covered and outright destroyed. The city’s Biblioteca Nazionale was completely flooded, soaking more than 1.5 million individual books. Nearly 500 sculptures were destroyed, and more than 1,000 paintings were completely destroyed or irreparably damaged. Many works in churches were also damaged by the floodwaters, which contained not just dirt and debris but other contaminants like gasoline. Restoration efforts were undertaken, but the task is nowhere near complete, even 40 years later. While many of the paintings have been painstakingly restored, about one-third of the works damaged in the flood still sit in the same condition they were in when they were pulled from the water.

3The Destruction Of the Library Of Al-Hakam II

A caliph who ruled in Islamic Spain from 961–976, Al-Hakam is remembered largely for his cultural and literary collections—what’s left of them, at least. While he ruled from Toledo, Spain, he sent collectors all over the world to acquire rare books, many documenting centuries of scientific study. Ancient works were brought back to Spain from as far away as Damascus, Alexandria, and Cairo. Over the course of his rule, he amassed a collection of about 400,000 books. We’re not entirely sure exactly how many were there, but the catalog of titles alone was said to take up 44 volumes. Unfortunately, Al-Hakam’s successor was considerably less open-minded. He declared the books in the library to be heresy, and while a handful were thought to have been saved, the rest were burned or buried at the bottom of the palace wells. There were so many books that it was said to have taken workers six months of labor to destroy them. One single book from the library survives today. It’s an ancient text of religious law, found in 1934 in the mosque of the Qarawiyyin.

2The Fire At The Palace Of Lausus

Lausus was a chamberlain in the court of Theodosius II, living in Constantinople around 420. He enjoyed a place within the court, and he used his position to secure the acquisition of statues from around the empire. Just what statues he acquired for his palace in Constantinople are up for debate. Many of the main sources we have regarding the palace contents were written a few centuries after fire tore through Constantinople and destroyed the eunuch’s palace. According to a sixth-century historian, the palace contained the white stone Cnidian Aphrodite and one of the seven wonders of the world—the Statue of Zeus that once sat in Olympia. Somewhere around 13 meters (42 ft) tall, the Statue of Zeus is referred to as the centerpiece of the massive palace, indicating the building’s size and opulence. Later writers also claim that the palace was home to the Hera of Samos and other Greek works of art. Still other works refer to an emerald stone statue of Athena, a winged Eos with drawn bow, and other statues of centaurs, satyrs, and other creatures from Greek mythology. In addition to the palace, the fire of 475 also destroyed a library with around 120,000 texts, including gold-lettered versions of the Illiad and the Odyssey.

1The Literary Inquisition Of The Ch’ing Empire

Hung-li officially rose to power in China in 1735 and became one of the most powerful forces ever to oversee the country. As part of his rule, he wanted to ensure that he and his fellow rulers were suitably respected. He established of a literary inquisition to rid the entire country of all works that spoke highly of his enemies or poorly of him, his family, and his dynasty. The emperor spearheaded the movement himself, and while it’s not known exactly what works were on the list of banned books, we do know that there were about 3,000 titles on the list. Over the course of the inquisition, his central book-collecting sites disposed of about 150,000 copies of text. The task of going door to door to search for banned works was assigned to lower-ranking government officials who had designs on advancing. Local provincial governments declared their own works on the banned books list and then submitted their lists to other areas of the government. The process is a blindingly confusing nightmare for historians to try to work through. Those that wrote the books suffered a fate similar to their writings. One man, Wang Hsi-hou, was accused of writing a piece that criticized the grandfather of their esteemed emperor. Not only was he executed, but his sons and his grandsons also paid the price—they were sold into slavery. Read More: Twitter