10Arguing Over Which Actor Was Better

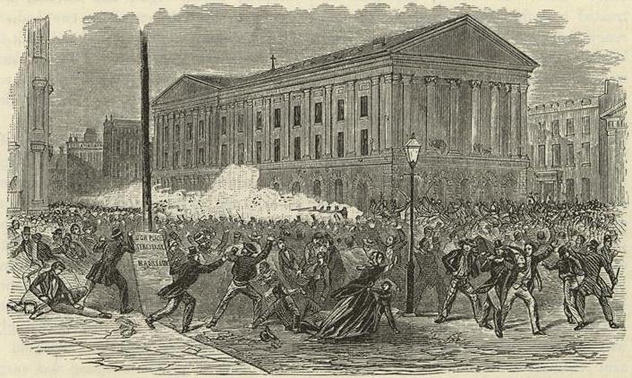

On May 10, 1849, an angry mob thousands strong, rampaged through the streets of New York, hurling paving stones and battling with the outnumbered police. Realizing they were losing control of the city, the authorities called in the militia, but a barrage of paving slabs forced the cavalry to retreat. Under heavy attack, the beleaguered infantry commander ordered his troops to fire into the air. When that failed to disperse the mob, he ordered them to fire a second volley into the crowd. Twenty-two people died. But at least they laid down their lives for a noble cause: arguing over which actor was better. The origins of the riot lay years earlier, when the acclaimed American actor, Edwin Forrest, agreed to a tour of Britain. Forrest was a tough Philadelphian, whose aggressive, muscular performances of Shakespeare had made him a huge star in his own country. His great rival was the British thespian William Charles Macready, and newspapers frequently ran pieces arguing which actor was better. When Macready toured America, Forrest followed him around, performing the same parts in rival theaters. For his part, Macready aggravated Forrest by condescendingly suggesting that he should study in England if he wanted to be great. When Forrest’s tour of Britain went poorly, he somehow blamed Macready. Tracking his rival to a theater in Edinburgh, he waited until a particularly effeminate flourish, then stood up and hissed loudly. Forrest’s actions scandalized polite society and destroyed his reputation in Britain—but only increased his popularity with working-class Americans, who were only too happy to see the stuffy Brit taken down a peg or two. When Macready scheduled another tour of America, Forrest’s fans were enraged. The Englishman was roundly booed everywhere he went, and at one performance was knocked off the stage by half a dead sheep, thrown by Forrest’s supporters. When Macready arrived to play Macbeth in New York, while Forrest was also there playing the same role, it was the final straw. His performance was interrupted by a hail of eggs, rotten fruit, and bottles of “foul-smelling” liquid. Outraged, Macready immediately made plans to leave for Britain, but was persuaded to stay by a group of wealthy New Yorkers, who talked him into one final performance at the swanky Astor Place Opera House. Forrest’s working-class fanbase was infuriated by what they saw as a betrayal by the city’s elites. On the night of the performance, a crowd of 10,000 attacked the Opera House, which was defended by the bulk of the city’s policemen. Amazingly, the performance went ahead, although the noise of the battle was so loud that the performers had to act in mime. Macready eventually snuck out in disguise and set sail for home, never to return.

9Nylon Stockings

In 1935, at the experimental labs of the DuPont Corporation, a brilliant research chemist named Walter Carothers was aimlessly playing around with some super-polymers. That’s when he noticed that, if he combined them with just the right amount of water, he could produce strong, flexible fibers. Carothers’s new material was named “nylon,” and it quickly became a sensation. Nylon stockings, stronger and easier to maintain than the traditional silk versions, became a must-have item for women everywhere—the initial run of four million pairs sold out in under two days. People just couldn’t get enough of the new wonder fabric. Then World War II broke out, and the nation’s entire nylon production was requisitioned to make parachutes and other military gear. The black market price of nylon stockings shot up to $20 a pair. Women took to drawing seams on their legs with paint, to give the impression that they could afford a pair. The stocking shortage became a hated symbol of wartime austerity. When the conflict ended, DuPont announced it would begin producing civilian nylon again, which created a huge stir. “Nylons for Christmas” became a popular slogan, as anticipation skyrocketed. It was a disaster. DuPont had severely overestimated how quickly it would be able to refocus production, and when a small number of stockings went on limited sale, riots erupted across the country. In Pittsburgh, 40,000 women lined up for almost two kilometers (1 mi) for only 13,000 pairs of stockings. Elsewhere, enraged mobs of fashion-frenzied women broke into department stores, smashed windows, and fought each other tooth-and-nail over the precious pairs of nylons. Crazed citizens accused DuPont of deliberately restricting supply to make a profit, and the company was forced to work overtime to get supply back up to pre-war levels. As more nylons became available, the riots eventually died out, having still done more damage to the 1940s American cities than the Japanese ever managed.

8Chariot Racing

In the first half of the sixth century, the venerable Byzantine Empire was riven by that timeless political scourge—sports hooliganism. Chariot racing was the Empire’s sport of choice, and supporters of the two most popular teams—the Blues and the Greens—frequently clashed in the streets after races. The Emperor, Justinian I, was said to be a fan of the Blues, although he had grown unpopular with hardcore supporters, after failing to favor the Blues over the other teams. Then, in 536, a number of fans were arrested and sentenced to hang for murder. But the execution was botched, and two prisoners—a Blue and a Green—escaped to take refuge in a temple, which was besieged by the authorities. Suddenly, and alarmingly, the two sides had a common cause. As Justinian presided over that week’s chariot race, the stadium was suddenly united in cries of “long life to the benevolent Greens and Blues!” Then, ominously, the chant changed again to a single cry of “Nika”—Greek for “conquer.” Shocked, Justinian retreated to his palace, while the mob attacked prisons and burned down government buildings throughout the city. Attempts to distract the rioters by scheduling new chariot races failed. Justinian, now besieged by the mob, was forced to give into demands that he dismiss hated city officials. Panicking, Justinian considered fleeing the city, but was talked out of it by his wife, the formidable Theodora. She declared “Never will I see the day when I am not saluted as empress.” Meanwhile, the hooligans, who were possibly getting a little carried away, were camped in the racetrack, attempting to declare one of their own Emperor. Justinian’s agents entered the camp and quietly reminded the Blues that the proposed new ruler was a Green. As the rioters descended into infighting, troops charged into their camp, trapping them in a dead end and slaughtering an estimated 30,000. The Blues and Greens were cowed for a few years, but by the end of Justinian’s reign they were back to fighting each other in the streets after races.

7Hats

These days, hat couture probably doesn’t seem like the kind of thing most people would violently riot over (although, apparently, Milan Fashion Week tends to descend into tavern-style brawling around day three). But back in 1920s New York, wearing a straw hat after September 15 was considered terribly gauche. So much so, in fact, that gangs of teenage hoodlums took to patrolling the streets, violently assaulting anyone caught sporting a straw boater. Newspapers of the day even started carrying articles, warning their readers when the 15th was approaching, so they could switch to a felt hat and avoid some fashion police brutality. The last straw came in 1922, when a particularly impatient gang of hat-hating youths decided to start grabbing hats two days early, on September 13th. But the hipster hooligans quickly found themselves out of their depth when they took on a group of dockworkers, who fought back in defense of their boaters. The violence quickly spread through the city, with roving bands of teenagers marching around, brandishing clubs with nails in them, brutally attacking anyone foolish enough to be seen wearing a straw hat. Order was only restored to the terrified city after several vicious battles between the police and the mobs. Miraculously, the “Straw Hat Riots” didn’t result in any deaths, although several people were hospitalized, and a number of youths were imprisoned. But even New York’s fashion fixation seems normal compared to the commotion supposedly caused by the invention of the top hat. A probably apocryphal story claims that, when the new creation was worn in public for the first time, riots broke out, women screamed and fainted, and dogs whined in terror. A child’s arm was broken by the surging mob, and the hat’s inventor was taken to court for wearing a headpiece “calculated to frighten timid people.”

6A Grilled Cheese Sandwich

Earlier this year, the staff at New York’s Rikers Island Correctional Facility were facing a tricky situation. Budget cuts had left the prison dangerously short on staff in the evenings. There were just enough guards to cope if everything went well, but if some sort of prison riot broke out, the officers would be powerless to intervene. Fortunately, everything seemed to be going according to plan—until one of the inmates tried to make himself a grilled cheese sandwich. The prisoner, a member of the Dominican Trinitarians gang, asked a rival Crip if he could use his hot plate to make the tasty treat. When the Crip refused, a fight broke out, which then spiraled into a huge riot between the two gangs. As many as 50 inmates fought a pitched battle, throwing chairs and attacking each other with brooms. One prisoner was even seen hurling a pan of boiling water at his rivals. With the outnumbered guards unable to break things up, the fight continued for almost an hour, until the gangs themselves agreed to stop whaling on each other and seek medical treatment. Reports did not mention whether the instigator ever managed to get his grilled cheese.

5A Weather Vane

In 1844, the new American consulate in Canton (now better known as Guangzhou) was experiencing some minor cultural friction with its Chinese neighbors. A particular point of contention was the consulate’s new weather vane, which took the form of a large gilt arrow, specially brought out from America. Unfortunately, to the local Chinese the arrow symbolized war, sickness, famine, and a whole host of other unpleasant things. Having a huge one swinging around in all directions was viewed as an insult, or worse—an attempt to disrupt the city’s feng shui, by directing negative energy around the place. The local government protested against the weather vane, but “little notice was taken of their remarks.” Then came one long, hot summer. The rice crop was low, causing hunger among Canton’s poor, and sickness was sweeping the city. As the population grew restless, the weather vane became the target of the community’s frustrations. Notices were posted, warning that if the Americans did not remove the offending arrow, the whole flagstaff would be torn down. The US consul, deciding that risking good relations over a decorative item was probably a bad idea, diplomatically agreed. But when the day came to remove the weather vane, the large Chinese crowd rioted, rushing forward and trying to seize the arrow. The Americans, somewhat less diplomatically, opened fire. A letter from the time laconically noted: “I have no doubt some Chinese were killed.” It took the arrival of 200 Chinese soldiers to restore order and ensure the weather vane was melted down.

4A Particularly Patriotic Opera

Back in the early 19th century, Belgium was ruled from Holland, as part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands—and they weren’t particularly happy about it. So it was probably a mistake for the Theatre Royale in Brussels to hold a special command performance, celebrating the birthday of the Dutch king. Especially since the opera they chose, Daniel Auber’s La Muette de Portici (The Mute Girl of Portici), told the inspirational story of a simple Neapolitan fisherman, who led an uprising against a tyrannical (Spanish) ruler. As the show progressed, the Belgian audience was moved to tears by the stirring tale of resistance and bravery. The opera culminated in the famously stirring and patriotic duet, “Amour Sacre de la Patrie” (“Sacred Love of the Fatherland”), at which point the audience, stirred into a nationalistic frenzy, started rioting. As the show ended, people surged forth from the opera house, attacking government buildings and burning down Dutch businesses. The rioters fought against government troops and even designed their own flag, as the situation turned into a full-blown rebellion. Within a few months, the Dutch had been forced out, and Belgium had been recognized as an independent country. Next time someone tries to tell you that opera is boring, remind them that it’s the only art form known to have started a successful revolution.

3Cheering Too Loudly

In 1066, William “the Conqueror” (better known in his own day as William “the Bastard”) had crossed the English Channel and defeated his rival—King Harold—on the blood-soaked grass of Hastings. Harold was killed in the heat of the battle, and William ordered his body to be thrown into the sea. But, as William raced towards London, his grip on England was still shaky. Harold’s surviving loyalists had crowned his young heir, Edgar, king. While William was easily able to deal with the child-king’s forces, he was still uncomfortably aware that he was not popular with the ordinary people of London. Shrewdly, William decided to hold his coronation on Christmas Day, calculating that everyone would be too busy celebrating the holiday to riot. Ironically, the coronation would actually be marred by the opposite problem: The people of London, eager to show their loyalty to their new ruler, turned out to be too enthusiastic about the ceremony. When the Bishop crowning William asked the crowd in Westminster Abbey to cheer for their new king, the response was so loud that the nervous troops stationed outside thought the king was being attacked by an angry mob inside the church. Panicking, William’s own troops rioted, setting fire to nearby buildings and rampaging through the streets and attacking passersby. Despite the audible screams and the fact that the church was now filling up with smoke William finished his coronation ceremony.

2A Cricket Match

Cricket has a reputation as a fairly boring, genteel sport—which is generally true, if only because it’s hard to find the stamina to riot for five straight days. But actually, one of the first ever international cricket matches descended into rioting so ridiculous, that even the most hardened soccer hooligan would have concluded everyone involved needed to sit down and take a long, hard look at their life. It all started when an English team, captained by the snooty Lord Harris, arrived for a tour of the antipodes. But, unlike the American Shakespeare fans from a previous entry, the Australian public held no ill will towards the aristocratic Brits—because they were far too busy hating each other. When the English team arrived to play a match in Sydney, the viewing public were outraged to discover that the umpire hailed from the rival city of Melbourne. To make matters worse, the umpire frequently gave decisions in favor of the visitors, and against the local Sydney boys. When Sydney’s star batsman was controversially given out, it was the final straw. The crowd surged onto the field and charged towards the players. Lord Harris was struck with a cane—his attacker was subsequently attacked by another English player—before two of his teammates uprooted a pair of stumps to use as clubs, and escorted him to safety. The incident created a minor diplomatic crisis between Australia and England, where it was suggested that the real reason for the riot was that the colonials had gambled heavily on an England loss, and were trying to get the game called off. Just to prove this was the most Australian story ever, one of the rioters was Banjo Paterson, who would go on to write “Waltzing Matilda.”

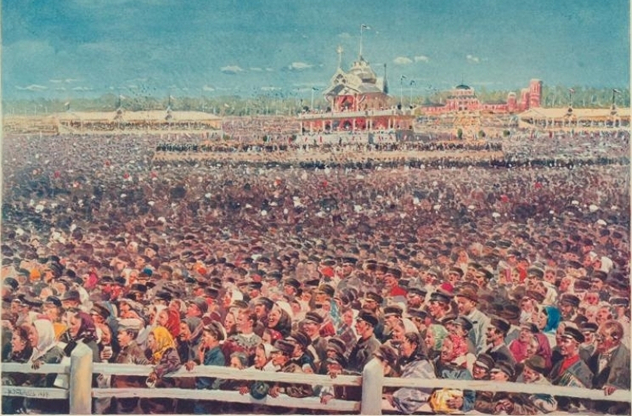

1Running Out Of Beer And Pretzels

If this list keeps returning to one theme, it’s that attending a coronation is never a good idea. On May 30, 1896, Nicholas II had just been crowned Tsar and Autocrat of All the Russians. To mark the occasion, his government decided to celebrate the only way Russians knew how—with booze. More specifically, they arranged for a huge banquet to be held for the people of Moscow. Every guest would receive a free cup, a piece of sausage, a pretzel, and all the beer they could drink. In preparation, 20 new bars were built on Khodynka Field, just outside the city. On the morning of the celebrations, an estimated 500,000 Muscovites began to gather around the field, held back by flimsy barricades and a few hundred Cossacks on horseback. As the morning wore on, the throngs began to grow restless. Then, like lightning, a rumor flashed through the crowd—the government had miscalculated and there wasn’t enough beer and pretzels for everyone. The panicked crowd surged through the barrier and rushed towards the food and drink. As hundreds of thousands of people pressed across Khodynka Field, many were crushed or trampled underfoot. The field was crossed by a number of small ravines and gullies, and Muscovites were forced into these by the unstoppable weight of the crowd. When the chaos dispersed, 1,389 people were dead, and many more thousands were injured. Many people blamed the Tsar’s uncle, Grand Duke Serge, who had been responsible for organizing the event and had failed to put proper safety features in place. When the Tsar called for an inquiry, Serge threatened to boycott the court if he was implicated, and the investigation was canceled. The Tsar’s uncles also persuaded him to attend a ball at the French embassy on the night of the tragedy, which didn’t do anything for his popularity among Moscow’s working class. Alex recently forgot the password to his Twitter account. See if he’s found it by now.