Retaining the ceremonial customs and protocols of the Mafia tradition, the Sicilian and Italian criminal fraternity were organized into hierarchical gangs, or “families,” reporting to what Luciano called the Commission. A criminal board of directors, the Commission consisted of the heads of the five New York families, as well as families from Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, and other major cities at various times. Murder, Inc. (as the name suggests) was even more businesslike. Freed from concerns about about ethnicity, tradition, or honor, they were focused on making money and accruing power. They were mostly hoods with other lines of illicit work, but given a salary as a retainer to carry out executions when ordered, and rewarded with extra pay upon completion of their task. This floating group, of anywhere from eight to 20 men at a given time, was the gang of killers the press dubbed “Murder, Inc.”

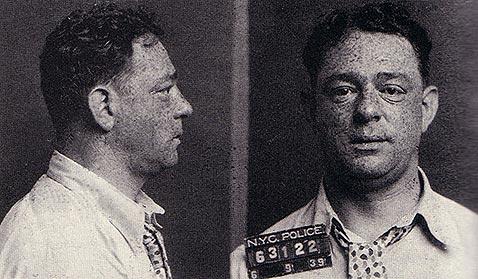

10Louis “Lepke” Buchalter

Apprenticed as one of the “Gorilla Boys,” a gang of young toughs who terrorized the Lower East Side of Manhattan and served as a farm team for gangsters in the area, Lepke became the pivotal figure in the Murder, Inc. story. Soon becoming a force in the New York garment union, Lepke often partnered with Thomas Lucchese and Albert Anastasia, captains in separate New York families. Both men were looking for a way to distance high-ranking mobsters from the violence they ordered. Both men were also ambitious, and saw an effective method of consolidating their power. The process was simple. Anastasia was the point man for the Commission, getting orders from his boss (at the time, Vincent Mangano), then relaying them to Buchalter. Lepke would then choose the best man for the job, dispatch the contract, and wait for confirmation that it had been carried out. No other information was given to the killer—the less they knew, the better. Unless otherwise ordered, the timing and method of execution were left at the executioner’s discretion. Most took great pride in their professionalism. Lepke, it seems, recognized early the benefits of employee empowerment. The killers were not “made men,” nor did they have any other connection to the crime families that contracted their services. After the orders were carried out, Lepke would receive his fee from the Commission, and pass on a share to the hit man. In the event of an arrest, he would work with the family officers to provide legal assistance—or whatever other action was deemed necessary to keep the protective wall around the Commission. Lepke soon branched out, accepting contracts from non-Commission sources, provided they didn’t conflict with Cosa Nostra wishes. Made men, for instance, could not be touched without an order from the Commission. It was a coolly effective process and it is estimated that over 400 contract executions were carried out by Buchalter’s team of killers. Lepke himself was a personally quiet and gracious man, known as a loyal husband and father and a generous boss. And he became the highest-ranking Mafia-connected figure ever executed by the state. In 1936, under investigation by district attorney Thomas Dewey on a variety of charges, an increasingly paranoid Buchalter ordered a hit of his own. He believed (incorrectly, as it turned out) that Thomas Rosen, a former industry driver and union official, was cooperating with Dewey. Rosen was shot to death as he left the candy store Lepke had given him. No one was immediately arrested for the murder. But two months later, Lepke and his long-time criminal partner Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro were convicted on anti-trust charges. The conviction was upheld on appeal, but the two skipped bail and disappeared in 1937. While on the lam, Buchalter was indicted on drug charges. Shapiro surrendered to authorities in April 1938, but Lepke remained underground until August 1939, when he surrendered to J. Edgar Hoover. He was sent to Leavenworth prison and convicted for the Rosen murder. In March 1944, after an appeals process that went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, he was sent to Sing Sing and executed in their electric chair.

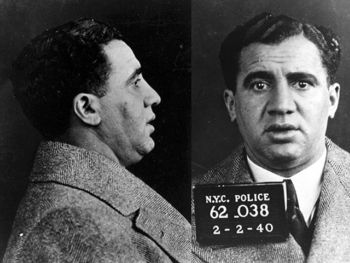

9Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro

Underworld legend has it that Jacob Shapiro and Lepke Buchalter became partners when, as teenaged thugs, they both tried to rob the same pushcart. Whether there’s any truth to that story is debatable, but what’s indisputable is that they soon became one of the most successful partnerships in the history of organized crime. Shapiro was two years older, and initially served as a mentor to Lepke. He had street smarts and an organic toughness that few possessed. But he lacked the vision and intellect of his younger partner. And while Lepke grew into a man of a certain refinement, Shapiro spoke as if he was gargling marbles (his nickname came from his slurring cry of “get outta here” to those who displeased him), and was often described as a “gorilla in a suit” for his slow countenance and thuggish appearance. But they were a perfect fit, Lepke’s brain and Gurrah’s brawn. Together they climbed the ladder of New York’s underworld, becoming friends and partners with future mob superstars like Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky. While Shapiro was a truly violent man, happy to do the “wet work” the mob bosses often required, his primary function in the Murder, Inc. organization was as a recruiter and developer of new talent. He was never convicted of a violent crime, but was in prison for extortion and conspiracy when he had a heart attack and died in 1947.

8Emanuel “Mendy” Weiss

One of Buchalter’s most trusted associates, Weiss was a union racketeer and drug dealer who became the second-in-command and chief “nuts and bolts” guy for Murder, Inc. He also took part in what is probably Murder, Inc.’s most famous hit—the killing of bootlegger Dutch Schultz. Hampered by serious legal issues, Schultz went to the Commission to request a hit be put on district attorney Thomas Dewey. When his request was refused as impractical, Schultz stormed out, insisting that he would do the job anyway. He may as well have put a “kill me now” sign on his backside. The Commission gave the order to Albert Anastasia, who relayed it to Buchalter. On October 23, 1935, Weiss and Charles “The Bug” Workman walked into the Palace Chop House in Newark and calmly told the restaurant staff to lie on the ground. Two of Schultz’s bodyguards and his accountant sat at a table, while Schultz himself was in the restroom. As Weiss opened fire on the table, Workman shot Schultz as he was washing his hands (or relieving himself—accounts vary). All four were mortally wounded. But the two bodyguards, Bernard Rosencrantz and Abe Landau, were able to stand and return fire. Weiss ran out of the restaurant and told the waiting driver, Seymour “Piggy” Schechter, to take off, leaving Workman to fend for himself. Workman avoided being shot, but had to make it back to New York by foot. The next day, he complained to Buchalter that Weiss had abandoned him at the scene of the crime, a capital offense within the organization. The rule was a practical one, as it lowered the possibility of a gunman being killed, or worse, taken into police custody. Someone had to pay the price. Mendy was too connected and too valuable. Poor Piggy Schechter paid for Weiss’s panic with his life. Weiss was later executed a few moments before his friend Lepke, in the same chair and for the same crime—the murder of Joseph Rosen.

7Louis Capone

Three men were executed for Rosen’s murder; in addition to Buchalter and Weiss, Louie Capone (no relation to Al Capone) took a seat in Sing Sing’s electric chair on March 4, 1944. Born in Naples and raised in Brooklyn, Capone opened a coffee and pastry restaurant and made connections with baking, trucking, and construction union leaders. Through these connections, he gained a foothold in union racketeering, and later began running loan-sharking operations out of his business. Capone’s restaurant had long been a hangout for the younger toughs in the neighborhood and he recruited some of them to take care of the “heavy lifting” his illicit businesses required. Among the young men who became his proteges were Abe “Kid Twist” Reles and Harry “Happy” Maione, who later became prolific and trusted hit men for Murder, Inc. Capone was connected to the Detroit gangs as well as his New York base. He became a valuable connection to bosses in both cities for his ability to recruit men willing to commit violent acts and keep quiet about it later. He was also known to be a successful mediator between criminal factions, including the rival Jewish and Italian gangs from which he recruited. Though not a trigger man himself, Capone was the primary business and human resource director for Murder, Inc., working closely with Buchalter as a recruiter, mediator, and tactical planner. His work in planning the Rosen murder sent him to Sing Sing, where he was the first of the trio to be executed.

6Frank “Dasher” Abbadando

A violent man, even by Murder, Inc. standards, Abbadando was a suave and psychopathic killer and sexual predator. When a prosecuting attorney reminded him he had admitted to at least one rape, he replied: “Well, that one doesn’t count really—I married the girl later.” A teenaged hood who specialized in extortion, he was convicted of beating a policeman and sent to reform school in upstate New York. He picked up his nickname there, displaying a skill for baseball with the speed that had made him a legend on the streets of Brooklyn. The story went that, after his gun jammed in an altercation with a neighborhood rival, he took off, running around the block with his intended victim now chasing him. Abbadando was so fast he lapped the block, came up behind his pursuer, and shot him in the back of the head. His preferred method of execution, though, was the ice pick, because “it don’t make too much noise.” He used it in many of the 30 murders he committed, including the vicious killing of loan shark and suspected informant George Rudnick. Abbadando and his crew stabbed Rudnick 63 times with an ice pick and meat cleaver, strangled him, and crushed his skull. Abbadando was convicted of the murder and executed at Sing Sing in 1942.

5Samuel “Red” Levine

Levine was a trusted trigger man even before the formation of the Commission, participating in the murders of both of the primary bosses during the Castellammarese War: Joe “The Boss” Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. The elimination of Masseria put Lucky Luciano in charge of one of the warring factions and allowed him to broker a peace treaty with Maranzano, whom he later had killed in order to eliminate his final obstacle to organizing an equitable Commission. Levine’s connection to Luciano, who used him as the head of his “Jewish hit squad,” a prototype of Murder, Inc., allowed him a smooth transition to the later enforcement unit. An observant Jew who refused to do business of any kind (including killing) on the Sabbath, Levine was also one of the few Murder, Inc. gunmen to avoid arrest or a violent death. By the late ’30s, as prosecutions were beginning to spell the end for the group, Levine seemed to drop off the radar. There is evidence that he was active in union work as late as 1970, but officially he lived the tranquil life of a retiree in New York until his death in 1972.

4Frankie Carbo

Frankie Carbo was one of the few gangsters to make the transition from a member of Murder, Inc. to a made man in a New York family. By the time the heyday of the organization was winding down, Carbo had been charged with five murders, but never convicted. Born Paolo Giovanni Carbo in the fertile gangster spawning ground of New York’s Lower East Side, he did his first stretch in reform school at the age of 11, before graduating from a street gang member to security and muscle for East Coast bootleggers. He later joined the Lucchese family and went on to become the mob’s point man in the boxing world, promoting and fixing fights in New York City, and “owning” an interest in the career and winnings of heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. He is also long thought to have been instrumental in the 1947 murder of Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, an early organizer of what became Murder, Inc., and the man credited with turning a seedy desert gambling town called Las Vegas into a glitzy vacation resort. Carbo did a stint in prison for extortion, but was released due to poor health. He died in Miami Beach in 1976.

3Vito “Chicken Head” Gurino

Called “Socks” or “Socko” by his friends, Gurino earned his better-known sobriquet from his unorthodox way of perfecting his marksmanship—he practiced by blowing the heads off live and running chickens. While many gangsters sought to project an image of sophistication and culture, Gurino had neither the aptitude nor the desire to appear a suave racketeer. He was morbidly obese, coarse, and slovenly. And it didn’t bother him a bit. What he lacked in finesse, he made up for in enthusiasm for his work. After he, Abbadando, and Harry “Happy” Maione murdered Cesaro Lattaro and Antonio Siciliano, two men trying to gain control of the Plasterers Union in New York, District Attorney William O’Dwyer described Gurino and his fellow assassins as men “killing for the love of it.” Gurino did occasionally use less violent methods. When told to ensure the silence of Joseph Libito, a witness to the George Rudnick murder, Gurino, perhaps overestimating his charm, took Libito to a house on Long Island, and gave him a meal. Libito, unnerved and convinced he was going to be killed, took the first opportunity to flee the house. He was arrested a few days later and taken to the Queens County jail. Gurino then contacted a corrupt deputy he knew. Walking into the cell of a shaking Libito, Gurino calmly asked him if he was going to be a “stand-up” guy. Libito replied positively and Gurino told him to ask the deputy for anything he needed. Libito asked for, and received, a few bucks for cigarettes, socks, and underwear. A few evenings later, Gurino showed up again and offered to take him for a late-night ride in the fresh air. Libito, once again thinking he was being set up for a kill, began arguing that he really didn’t want go and Gurino left when the conversation became heated. Libito then not only told the deputy that he didn’t want Gurino allowed back in, he notified his lawyer, who set an investigation into motion that resulted in the deputy being convicted of obstructing justice. Gurino’s attempted diplomacy proved to be his undoing. Already known as a criminal associate and suspected of several gangland murders, he was now implicated in a corruption investigation, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. He was caught several months later, screaming hysterically as he was led from the church where he had been hiding. In exchange for his confession to three other murders, Gurino was given a pass on the electric chair and died 17 years later in the Danemora Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

2Oscar “The Poet” Friedman

One of the odder characters in the New York underworld, Friedman was a relatively small-time fence of stolen goods. Skinny, long-haired, perpetually disheveled, and a lover of classical poetry, Oscar ran the disposal department of the Murder, Inc. motor pool. A member of the theft and loan-sharking gang led by company man Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, Friedman convinced Reles and his bosses that he had a secret, foolproof method for disposing of the cars used in their assignments (the method was said to involve acid, a blowtorch, and his genius for reverse alchemy). For 50 bucks a vehicle, Oscar would see to it that the evidence was irrevocably destroyed. He soon became a valuable cog in the Murder, Inc. machine. “Give it to Oscar” became organization shorthand for “mission complete” and many a hit man handed over the keys to their designated vehicle with a mixture of relief and triumph. As it turned out, Oscar had no such disposal method. He simply sold the cars to a junk dealer he knew, who stripped them and sold them for parts. He was later ratted out to the authorities, an informant telling cops that he could be found in the park reading from a worn anthology of poetry he kept with him. Which was exactly where and how he was found. Friedman later turned informant himself, eventually revealing the junkyard where parts from several vehicles used in Murder, Inc. crimes could be found. The prosecutor who interviewed him later said he was “the only man that ever outsmarted the gang.” Friedman later insisted that not only was the book of poetry planted on him, but that he was illiterate. He probably did so in an effort to thwart revenge. After his release from prison, he was never heard from again.

1Abe “Kid Twist” Reles

So, if Murder, Inc. was such an efficient operation, how did it crumble? Some have argued that, lacking the Cosa Nostra’s dedication to “family honor” and tradition of “omerta” (silence), it was only a matter of time before someone turned rat to save their own skin. One of the organization’s most feared gunmen was Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, a diminutive but violent sociopath. Nicknamed after a New York gang leader from an earlier era (Mac “Kid Twist” Zweifach), Abe was a paid killer who enjoyed his work. He was an ice pick virtuoso, supposedly able to wield the instrument so adroitly he could make it appear, by stabbing his victim in the ear, as if they had died as the result of a brain hemorrhage. In 1940, Reles had become the target of a criminal investigation. Implicated in several killings and facing probable execution, he became a government witness, and the most famous “stool pigeon” in organized crime up to that point. Every man on this list who went to the electric chair did so as a result of Reles’s testimony. He essentially brought down the whole operation. Reles was prepared to live out his life in cushy government protection. Then he was called on to give testimony against Albert Anastasia, a made man, captain in the Mangano family, and liaison between the Commission and Murder, Inc. Anastasia had been implicated in the murder of union activist Pete Panto and the state’s case was based almost entirely on Reles, who was being kept under protective custody, guarded by a group of six police detectives at the Half Moon Hotel on Coney island. The trial was to begin on November 12, 1941. In the early hours of that morning, Reles tumbled to his death from the window of his room. A 1951 grand jury concluded that the death was accidental. Many are unconvinced of that conclusion. It did earn Reles another nickname, though. He was known ever after, in underworld lore, as ”The Canary Who Could Sing . . . But Could Not Fly.”

+Harry “Pittsburgh Phil” Strauss

“Pittsburgh Phil” was the ace of the Murder, Inc. crew. A meticulous planner, he was equally adept with a gun, a rope, and the tool that became an underworld cliche—the ice pick. He refused to carry a weapon in case he was stopped by the police. But he would study his victim and the proposed murder site to figure out the best method of execution. He is considered the group’s most prolific killer, with over 100 hits to his credit. He was eventually convicted of the particularly violent 1939 slaying of Irving “Puggy” Feinsten. Feinstein, a racketeer attempting to move in on the wrong turf, fought back and bit a few chunks out of Strauss’s finger. Angered, Strauss and his associates tied Feinstein in a position that put pressure on his arms and legs, causing him to struggle and slowly strangle himself to death. They then took the body to a vacant lot and burned it. Strauss had a more mundane exit, at least by hitman standards, electrocuted at Sing Sing in 1941. Brent Sanders is a writer, musician, and free-lance neurosurgeon who lives in a bomb shelter in suburban Appalachia. He occasionally rants about music, politics, and sports at www.ubermullet.com.