10Ravens Understand Espionage

Ravens can’t stop impressing us with their sharp mental game and have just claimed another superlative for the corvid family—the animal kingdom’s best (non-human) abstract thinkers. Scientists wondered: Are ravens able to consider the thoughts of others as they make decisions? Can they get into others’ heads? To find out, University of Vienna researchers employed 10 ravens—all raised in captivity—and placed them, two at a time, on either side of a room separated down the middle by a window. In clear view of the other bird, each received a treat to hide and did so with great care to shield it from prying eyes. Next, researchers shuttered the window but introduced a peephole. The ravens were taught to peer through the hole as scientists hid food within the adjoining, now empty, chamber, and then were allowed inside to retrieve the treats. With the purpose of the peephole established, the ravens were asked once more to hide their food, this time with a peepholed window. They were tested with it closed or open and with simulated raven sounds piped into the room. Amazingly, the ravens were more careful in hiding their food only when the peephole was open because they knew that only then could they be spied on, regardless of soundtrack filtering through.

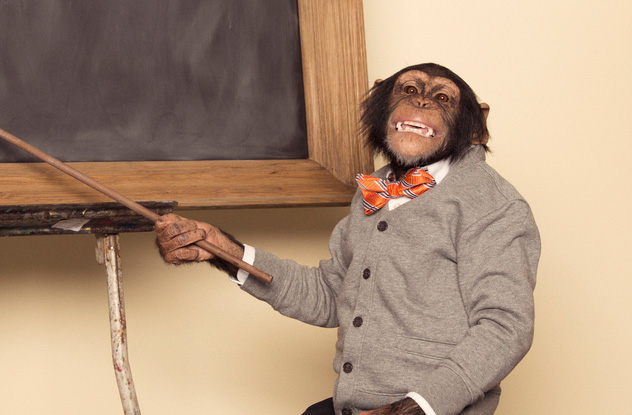

9Chimps Know What They Know

A perk of high intelligence is the ability gauge one’s own knowledge, though overestimations in this department have landed many past humans in trouble. This metacognitive monitoring, or knowing what you don’t know, was thought unique to humans for a while. Then chimpanzees proved that they too possess the intellectual tools for metacognition. The three chimpanzees chosen for the study were given memory tests of varying difficulties and after a short delay received a computerized “pass” or “fail” alert. Correct answers also released a treat. But the yummy offering was dispensed some distance away from the testing module, so that prolonged dalliances meant losing the snack forever. Therefore, the chimps faced a dilemma. They could stick around and receive their score or prematurely dart off toward the potential foodstuffs. The early absconders were mostly correct, proving themselves honest judges of their knowledge. According to the researchers, this same confidence dictates many facets of chimp life. From fearlessly swinging across branches to tracking down trees with freshly ripened fruits, chimps prefer to act when they’re sure of success.

8Cats Recognize You, Don’t Care

The latest cat science from the University of Tokyo has confirmed what cat owners feared and dog owners boasted since time immemorial: Your kitty doesn’t care about you. Researchers enlisted 20 pet cats in a study to ascertain whether felines recognize their owner’s voice. Each cat was tested in its home (to avoid undue stress and the overstimulation of a new environment) and subjected to several audio recordings. First, three strangers’ voices called kitty’s name. Then, the cat’s owner did the same. Then came one final stranger, to thoroughly confuse the feline. Based on body language, researchers concluded that cats indeed discriminate between different voices and are cognizant of their owner’s unique acoustic profile. Unfortunately, it didn’t matter. Most participants could not deign to respond to the call with anything other than absolute apathy. Unlike dogs, who are always at the ready to reciprocate attention, only 10 percent of the cats in the study answered their owners with a meow. But then again, maybe we shouldn’t expect too much in the way of geniality from a semi-domesticated creature, no matter how floofy.

7Dogs Recognize, Attempt To Diffuse Your Anger

Dog scientists from the University of Helsinki have confirmed that pooches are privy to their master’s moods. Fido not only gauges your anger but has learned how to shift his or her demeanor to diffuse it. Thirty-one dogs across 13 different breeds were rounded up for the Finnish study, and each was subjected to images of dog and human faces displaying a range of emotion: threatening, neutral, and pleasant. When confronted with a human face, the dogs first checked out the eyes before zooming out to consider the whole visage at once. When presented with other canines they averted their gaze toward the muzzle rather than the eyes. The response was also suitably different. Dogs didn’t shy away from locking eyes with angry brethren but knew to avoid direct eye contact with a pissed-off human, instead opting for that trademark, impossible-to-resist innocent look. So, thanks to countless rounds of domestication, dogs have learned the intricacies of the human face and how to transform a potential reprimand into a head-pat.

6Capuchins Confront Unjust Treatment

It turns out that humans are only one of the nine primate species that recognize unfair treatment. In fact, confronting injustice may be an evolutionary reflex developed to foster cooperation and increase survivability for social creatures. In the amazing video above, two capuchin monkeys learn that they will receive a treat for handing the experimenter a rock. Capuchin A does so and is duly awarded a piece of cucumber. Not a bad day’s work. But capuchin B’s reward for completing the same task is a much sweeter grape. Capuchin A immediately notices the discrepancy and now expects to be similarly rewarded on the next round of rocky-handy. But the researcher once again offers Capuchin A cucumber, which is now the equivalent of poison compared to delectable grapes. So, like an unruly child, capuchin A indignantly flings the slice of cucumber, threatens the experimenter in Capuchinese, and bangs on the table with vengeance on its mind. By the third go-round, capuchin A is genuinely flustered and does something remarkable—it tests the rock against the wall of its enclosure to confirm its quality.

5Lizards Learn Quickly

Flexible behavior is the ability to intuit fresh solutions when confronted with previously unfaced problems. The smartest animals consistently rebuke scientists’ attempts to fool them, but such tests aren’t often administered to lowly, cold-blooded creatures. Warm-blooded animals have much more energy to expand toward learning novel tasks, but could a group of lethargic lizards be coerced into learning new tricks? The answer, as in all animal studies, is food. In a study led by Manuel Leal, behavioral ecologist at Duke University, the tropical Anolis Evermanni lizard surprised everyone with a propensity for assimilation typically reserved to fuzzier clades. Researchers hid fun-sized worm larvae—a treat nonpareil for lizards—beneath blue disks. Since these lizards hunt by scampering up trees, they have no experience in digging for food, yet they found different ways to dislodge the disk, either by mouth or snout. When a yellow-bordered disk was brought in as well, the lizards stuck to the blue disks they knew were a sure bet—until the location of the treat was switched. This new test stumped some of the less gifted students, but a couple realized the switch and profited gastronomically. Overall, they performed like the supposedly smarter birds of similar studies, though lizards deserve extra credit on account of their cold-bloodedness. Warm-bloods eat often and can be drilled on new lesson plans several times a day. But the languorous, cold-blooded lizards eat only once daily and compensate by doing absolutely nothing else.

4City Birds Are Smarter

Rampant urbanization is detrimental to animals in many ways, yet science has now found a small silver lining—city birds are becoming smarter than their country-dwelling cousins. A team from Montreal’s McGill University found that the challenges of city living make birds more resourceful, resilient, and likelier to innovate new ways to exploit their rich environment. The first-of-its-kind study was carried out at McGill Bellairs in sunny Barbados because the island spans the spectrum of urbanization, from booming development to unfazed rural. Researchers collected 53 bullfinches from across the island, getting a good mix of the urban as well as spitoon-using country bullfinches. The birds were presented a small puzzle, which required them to pull a slide and remove a cap to access a pile of birdseed. The bullfinches from more developed sectors were quicker on the draw, showing that their cosmopolitan lifestyle had positively affected their cognition. Adding insult to injury, city birds also boasted hardier immune systems compared to their rustic brethren, because sometimes life isn’t fair.

3Drunk Bees Get Punished

Honey bees enjoy an intricate social system that keeps the community functioning with machine efficiency. Naturally, researchers wondered whether they could disrupt the natural order by adding alcohol to the equation. So scientists delivered a sucrose-and-2.5-percent-weight-by-volume wine spritzer right to the forager bees’ tiny proboscises. Though the experimental ethanol beverage did not alter “the relative frequency or proportion of time” bees spent engaged in essential tasks, it did “significantly decrease” the duration of basic bee behaviors like walking around and social food exchanges. Just like humans, the harmonious bee community was disrupted by the inhibition-lubricating effects of booze. But the world is full of fermenting goodies, and bees can become intoxicated naturally as well. In the wild, alcohol-by-volume and intake cannot be controlled as in the lab, and real-world bees get sloppy drunk. The sloshed bees are accident-prone and become a detriment to abstinent bees, so drunks are welcomed home by colleagues—who immediately punish the offender by pulling off limbs, an inconvenience that sometimes leads to death.

2Ant Movers Rely On Foremen

Ants also display incredible acts of cooperation, thanks to a decentralized intelligence agency, pheromones, and an unbreakable dedication to role. As a result, ants easily move objects much larger than themselves. But how do they do it? To find out, one of the lead authors, Ehud Fonio, devised an experiment based on an unsavory apartment-living experience. Long ago, he discovered his former abode inhabited by a legion of longhorn crazy ants. The ants, named for their inebriated walking swagger, routinely undertook expeditions to pilfer bits of cat food. So Fonio baited the study ants with cat-food-scented Cheerios as well as a much larger ring, because the taste for kibble is apparently inherent. He tracked and numbered the ants as they joined in on a massive Cheerio relocation effort so that he could follow individuals as well as analyze the collective ebb and flow. The secret to efficient transport is the ratio of “movers” to “leaders.” A large group, the movers, link forces to push or pull the desired object. But they are supplemented by free-roaming leaders, who pop in to direct the laborers toward the nest. Eventually, leaders join in to lend additional muscle as manual laborers but soon lose track of direction. So new leaders must periodically jump in to orchestrate the effort, though if the group grows too large, the process is jeopardized.

1Elephants Recognize Voices

Like the Internet, elephants store away memories indefinitely. In a real-life scene from Dumbo, two estranged acquaintances at The Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee enjoyed the pachyderm equivalent of a tearful reunion after 23 years apart. It began as a meet-and-greet between incumbent elephant Jenny and the new girl Shirley, yet to everyone’s surprise, the two greeted each other like drunk sailors. Later, confused elephant tenders checked Shirley’s personal record and found that long ago, she and Jenny had both served in Carson & Barnes Circus. Even though their tenures overlapped only a few months, they recognized each other over two decades later. But that’s nothing—one study revealed that elephants can keep track of 30 relatives and friends based only on urine. But the power of recognition transcends species, and the clever elephants at Kenya’s Ambroseli National Park can identify humans by voice, discerning age, sex, and at least two separate languages. Researchers recorded two local peoples, the Maasai and Kamba, uttering the same phrase. They then played the recordings from a hidden loudspeaker for all elephants to hear. The elephants knew when women or children were speaking and could pick out Maasai and Kamba dialects, even when significantly distorted. This useful survival adaptation allows them to avoid the cattle-herding Maasai men, who are known to spear the poor animals.