10Sarum Ordinal Page

When a librarian at England’s University of Reading found a page of writing hidden in an archive, she immediately knew it was something extraordinary. Both sides of the paper bore red paragraph marks and black-letter typeface. This identified the incredibly rare page as belonging to a book printed by William Caxton,[1] who started the first printing press in England. Printed between 1476 and 1477, the “Sarum Ordinal” or “Sarum Pye” was a handbook written in Latin by St. Osmund, an 11th-century bishop. It was a guide for priests on what to wear and which Bible texts to use during religious festivals. At some point the page was ripped from the now-missing book and used to strengthen another’s spine. There it remained for 300 years until a librarian rescued it in 1820. However, not realizing it was an unknown Caxton leaf, the person stored it and another 200 years passed. Despite its age, getting torn and pasted into another book, the leaf is in good condition. The only other remains of a Caxton printed Sarum Ordinal are eight pages kept at the British Library in London.

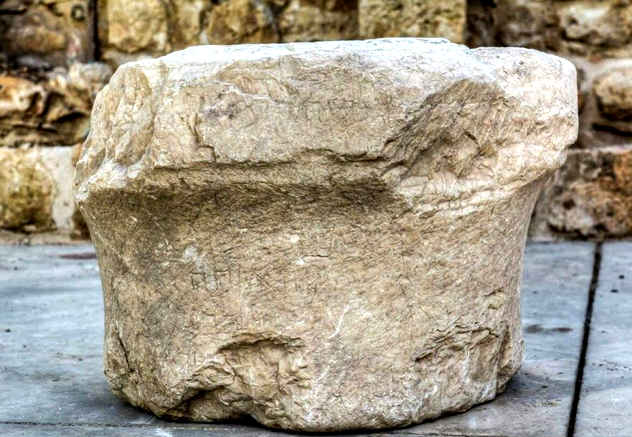

9The Donor Stone

In Western Galilee, the town of Peqi’in is around 2,000 years old. During recent renovations at the ancient synagogue, a large artifact was found.[2] Inside the courtyard was a limestone pillar bearing two inscriptions in Hebrew. Carved during Roman times, the 1,800-year-old column was curiously placed upside down for some reason. Researchers studied the engravings and concurred that they appeared to be a list of names, honoring those who had made donations to the synagogue. Peqi’in is deeply steeped in Jewish history, and the exact location is still a bone of contention. However, some experts feel that the stone enriches the settlement’s story during the Roman and Byzantine eras, and that the artifact proves the site is indeed the Peqi’in community mentioned in the ancient scriptures. To find evidence that strongly supports one of Galilee’s most significant sites is a historical step for Israeli archaeology.

8Earliest Buddhist Shrine

Legend has it that the Buddha was born under a tree at Lumbini[3] in modern day Nepal. Depending on the tradition, the year was 623 B.C. or closer to 400 B.C. Most Buddhism schools prefer the latter. By 249 B.C. Lumbini represented one of the religion’s most sacred sites. Recently, archaeologists burrowed underneath a central shrine. They were stunned to discover the brick building stood on an older wooden structure. Everything pointed to the timber ruins as being a holy Buddhist site. The design was near-identical to the more recent shrine. In the middle were tree roots surrounded by post holes, indicating that a wooden railing once circled a bodhigara (tree shrine). The clay floor had seen heavy foot traffic, possibly from worshipers, and befitting Buddhism’s no killing stance; there were no signs of sacrifices. Scientific studies placed the bodhigara at around 550 B.C. For most traditions, this could revise the Buddha’s birth by more than a century, and although more analysis is pending, the site is a good contender for the earliest Buddhist shrine ever found.

7Mother-Of-Pearl Menorah

In 2017, excavations at the ancient Roman city of Caesarea in Israel produced discoveries almost on a daily basis.[4] King Herod built a temple there in the first century B.C. and dedicated it to his patron Augustus Caesar. During its day, the temple dominated the port, and some of the finds within its walls were a partial Greek inscription and an altar. However, it was only when restoration work was being done nearby that the most significant find emerged—a small slab of mother-of-pearl. Carved on the tablet’s surface was a six-branched menorah. The artifact was unique for its precious material and Jewish iconography. Experts are almost certain that it was once part of a box. More specifically, a container that likely held a Sefer Torah scroll. This handwritten text holds the first five books of the Old Testament and is fundamental to Jewish law. The 1,500-year-old carving was created during the late Roman-Byzantine era and shows that Caesarea had a Jewish population during that time.

6Mithraism on Corsica

Mithra was a mysterious Indo-Iranian god whose following took root alongside Christianity in the Western world.[5] Christianity is well documented, but almost nothing is known about Mithraism except that the primitive religion worshiped a single deity and was probably all-male at first. The best chance to study it comes from sanctuaries dedicated to Mithra, and one was recently found on Corsica. In 2016, archaeologists swept the area after local authorities wanted to build roads near Mariana, a Roman town from around 100 B.C. That is when they found the sanctuary’s antechamber and worship room. A first for the French island, it proved that Mithraism was practiced in Corsica. Artifacts ranged from the bland (oil lamps and pottery) to a rare marble tableau showing Mithra himself sacrificing a bull. Some items, such as the broken altar, received damage in antiquity. The ancient Christian center at Mariana cannot be directly linked to the destruction, but it is likely that there existed a mutual tension. The two religions competed for followers and Roman Emperor Theodosius I, favoring Christianity, outlawed and persecuted the growth of Mithraism.

5 The Funeral Garden

Egyptologists long suspected the existence of gardens for the dead. Inside ancient tombs, murals sometimes show such gardens.[6] In 2017, one was discovered at a necropolis on the Dra Abu el-Naga hill, in Luxor (ancient Thebes). Found outside the entrance of a 4,000-year-old tomb, the garden was a neat, rectangular structure, 3 m x 2 m x half a meter high (10 ft x 6.5 ft x 1.6 ft). Inside were rows of 30 cm2 (4.65 in2) blocks. One corner bed holds a tamarisk shrub and a bowl with fruit, perhaps given as an offering. Two trees flank the garden and more probably stood at its raised center. Additional research is needed to find out what else grew in the grid but experts believe the plants were chosen based on their connections to Egyptian religious beliefs. Possible species are sycamore, palm, and Persea trees, even lettuce since they all symbolized renewal and resurrection. The unique garden was the first time iconography was confirmed by a physical discovery, and the find could also reveal what Thebe’s environment, botany, and religion entailed during a crucial time when the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt merged.

4The Beardless Jesus

Archaeologists got more than they bargained for when they investigated the ancient city of Castulo in southern Spain.[7] Between the ruins were glass shards with images. When reassembled, a history-changing plate from the fourth century emerged. Although about 20 percent of the artifact remains missing, there was enough to identify it as a plate used to serve Eucharistic bread. But it was not the plate’s purpose that shocked the archaeologists. Together, the shards revealed the image of a beardless Jesus wearing a Roman toga. With him were the apostles Paul and Peter, also clean-shaven and swathed in togas. Each man’s hair was also cropped short. Around this time, Christianity often faced Roman persecution, and any visual reference to Christ used a symbol such as the shape of a fish. This discovery could force a rewrite of the religion’s history in Spain and how much Roman influence occurred during early Christian art. Since it was made of glass, it is likely that it was forged in Ostia, near Rome, and it remains one of the earliest images of Christ and the apostles ever discovered.

3The Connecticut Mikveh

When Stuart Miller was asked to visit an old ritual slaughterhouse, he didn’t expect fireworks. Miller was an expert on ancient mikvehs (Jewish ritual baths) and sites in Israel around 2,000 years old.[8] The idea of a 19th-century farming community in Connecticut delivering any surprises was almost ridiculous. Even historians believed that the Jewish immigrants who lived at Old Chesterfield had abandoned their religious laws. Incredibly, Miller found a mikveh and the discovery changed Jewish history in the US. Due to the young age of the site, Miller expected a modern mikveh, but instead of a tiled pool, the bath consisted of stone, concrete floors, and wooden stairs and walls. Not only did it resemble ancient baths in Israel, but a pipe feeding water from a local pond adhered to the law of only using water from the heavens or the earth. Clearly, the Jewish community at Chesterfield did not abandon all laws and kept one of their most ancient rituals intact. Any 19th-century American mikveh is scarce enough, but the Chesterfield bath remains a unique example.

2Hezekiah’s Gate

According to the Hebrew Bible, King Hezekiah despised false idols, and he destroyed everything related to his father’s godless beliefs.[9] Decades ago, a gate was found in the city of Tel Lachish, and excavations in 2016 cleared most of the structure. The six rooms covered an area of 80-by-80-foot (24.5 by 24.5 m) and today stands about 13 feet (4 m) high. It doubled as a shrine and was likely also forcibly retired by Hezekiah in the eighth century B.C. According to the Bible, the gates of Tel Lachish was an important social hub where the elite would sit on benches. The building’s size, as well as seats found inside, indicated that the ruins belonged to the historical shrine-gate. In an upstairs room, researchers also found two altars. Each had four horns, all of them with intentional damage, another possible sign of Hezekiah’s intolerance. Elsewhere in the shrine was a stone toilet. Biblical texts mention the placement of latrines at cult centers as a method of desecration. Tests proved the toilet had never been used and was probably installed for such desecration purposes.

1The Crucifixion Bone

There is an oddity regarding crucifixion.[10] It is well documented, and the Romans executed thousands of people this way. Yet, no physical evidence of a crucifixion ever came to light. Not a cross, nor any skeleton bearing the gruesome scars of being nailed to wood. At the Israel Museum, archaeologists had another look at a stone coffin, or ossuary, containing a man’s bones. Inside, they found the only physical evidence of crucifixion, and it painted a different picture of the event than what artists had depicted over the centuries. The victim was a young Jew in his twenties, named Yehohanan. What his transgression was will never be known, but 2,000 years ago in Jerusalem, he died on a cross. Forced deeply into the heel bone was an iron nail. This revealed an unknown crucifixion technique. Most Christian iconography places Jesus with his feet staked to the front of the cross. Yehohanan’s feet had been nailed to the sides of the vertical beam. His hands were also undamaged, hinting that his arms were held in place against the horizontal bar with ropes instead of nails through the wrists. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages