In some cases of these cases, the miscarriage of justice was caused by unfortunate happenstance. In others, the blame falls upon neglect or willful interference by the police and judiciary, whose responsibility it was to ensure that the suspect was granted a fair trial. Here are ten people who definitely didn’t do it.

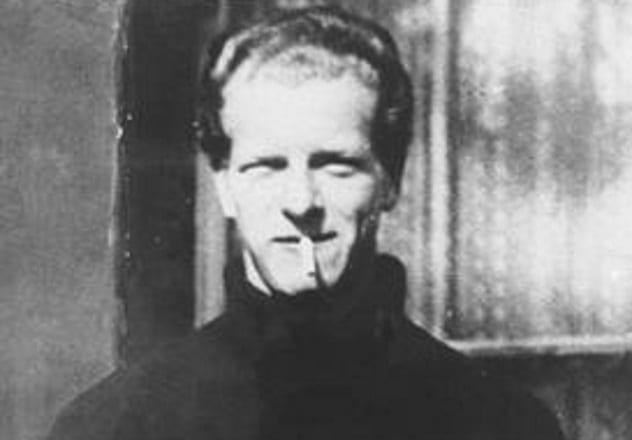

10 Harry Gleeson

Moll McCarthy was murdered in in County Tipperary, Ireland, in 1940. Moll was well-known in the town as a prostitute. She’d had seven children in the course of her business and had named them all after their fathers, to the embarrassment of the town as a whole and certain gentlemen in particular. There was some concern at the time that Moll might also have been an informant against the IRA, either willingly or as a result of her indiscreet nature. Harry Gleeson discovered Moll’s body in his uncle’s field. She had been shot twice in the face. When questioned, the farmer denied knowing who she was, perhaps from a simple desire not to be associated with the notorious woman. However, the lie brought him under suspicion, and he was charged with her murder.[1] It was suggested that he had fathered one of her children and had killed her to stop her from talking. However, there was no evidence for this. Witnesses came forward who could refute this claim, but they were never called at the trial. The police also withheld evidence which would have exonerated Gleeson, and the medical evidence, where it existed at all, was flawed. The only thing that linked Harry Gleeson with Moll McCarthy was his discovery of her body. And the only damning evidence against him was the fact that he had lied about knowing a known prostitute, who may have been an IRA informant and was found murdered and disfigured in his uncle’s field, which seems, on the face of it, entirely understandable. Harry Gleeson was convicted and executed in 1941. He was officially pardoned by the Irish president, Michael Higgins, in 2015.

9 John Perry

In 1660, William Harrison, an estate manager, went to Campden, England, on foot to collect rents, as was his normal routine. He never returned. After a time, his servant John Perry, and Perry’s son, went out in search of their master, but the only trace they could find was their employer’s hat, shirt, and collar, which Perry claimed to have found abandoned along the road. The items were stained with blood. John Perry was arrested for Harrison’s murder. When questioned, shall we say, somewhat forcefully, he accused his own mother and brother of being the real murderers, saying that they had killed William Harrison for his money. At the trial, John Perry acknowledged that the idea to kill Harrison had been his own, which made him just as guilty. He went into great detail about who had done the killings and what was said and done by each plotter. However, the judge refused to find them guilty of murder without a body. They were charged with robbery but were offered a pardon even for this. However, John Perry kept insisting not only on his own guilt but also that of his mother and brother. Eventually, a second judge decided that they could be charged without a corpse, and given Perry’s claims, the entire Perry family was found guilty and hanged in 1661. John Perry was hanged last, after being forced to watch the executions of his mother and brother, and his body was ordered to remain at the gallows until it putrefied. That would have been all there was to it if, in 1662, the “victim” hadn’t returned. William Harrison told a wild story of having been attacked by pirates, who robbed him, chained him up, and threw him into a pit. Then they inexplicably came back for him, gave him money, rode him about 260 kilometers (160 mi) to the coast, and sold the arthritic 70-year-old gentleman into slavery upon a ship. He then, if you could believe it (which you really couldn’t), was taken by Turkish pirates, but a doctor rescued him and put him to work managing a distillery until unspecified friends found him, quite by chance, and paid his passage home. His tale was clearly a complete fabrication, but wherever he had been, and whatever he had been doing, he was certainly not being murdered on a road in Campden by John Perry or, indeed, any of his unfortunate family.[2]

8 Timothy Evans

Timothy Evans moved into a top-floor flat at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, London, in 1948 with his wife Beryl and their daughter. The ground floor was occupied by a man named John Christie. Timothy Evans, though industrious, was a man of limited intelligence and virtually illiterate. He found it difficult to support his family, and when his wife announced she was pregnant again, it was decided that she would have an abortion, despite this being illegal. On November 30, 1949, Evans went to the police. After some confusion in his story, he eventually told them that his neighbor had performed the abortion on his wife and that she had died as a result. He also said that his daughter had been taken and given to an unknown person to look after and that Christie was refusing to let him see her. When police searched the house, they found the bodies of both his wife and his daughter, barely concealed in the washhouse. They had both been strangled. Evans was said to have confessed to killing his wife, though it was later proved that most of his confession was effectively written by the police and presented to the illiterate man to sign. There was no forensic evidence. Evans insisted that John Christie had committed the crime. However, it took a jury just 40 minutes to convict Timothy Evans, and he was hanged on March 9, 1950. Three years later, the police discovered a number of other bodies at 10 Rillington Place. There was even a woman’s thighbone blatantly propping up John Christie’s garden fence. Some of these bodies would certainly have been at the property at the time the police searched the place, but it seems they never looked further than the washhouse. John Christie was himself hanged in July 1953 for the murder of at least eight people. In 1966, the entirely innocent Timothy Evans was finally given a royal pardon.[3]

7 Derek Bentley

Derek Bentley had the mental age of an 11-year-old. In November 1952, Bentley, 19, and his 16-year-old friend Christopher Craig broke into a confectionery warehouse. When the alarm was triggered, and the police arrived, the two young men tried to hide on the roof. Soon after, DC Frederick Fairfax climbed onto the roof and chased them, grabbing Bentley. Bentley broke free, and as he ran, he is said to have called out the fatal words, “Let him have it.” Christopher Craig fired his gun wildly, hitting and wounding Fairfax. However, his wounds were not substantial, since he was soon on his feet again. DC Fairfax recaptured Bentley and “flattened him” with a punch before arresting him.[7] Some 15 minutes after Bentley was taken into custody, PC Sidney Miles kicked open the door to the roof where Christopher Craig was still holed up, whereupon Craig shot him in the head. Craig continued to fire at police until he ran out of bullets. Then he leaped from the roof, breaking his spine in the fall. At the trial, the prosecution alleged that Bentley egged Craig on by yelling, “Let them have it,” while the defense maintained he was trying to get Craig to give up the gun. Both men were found guilty of murder, even though Bentley was under arrest and no longer on the roof at the time of the shooting. Since Craig was only 16, however, he could not be executed. Derek Bentley was hanged in January 1953 and was granted a limited pardon in 1993.

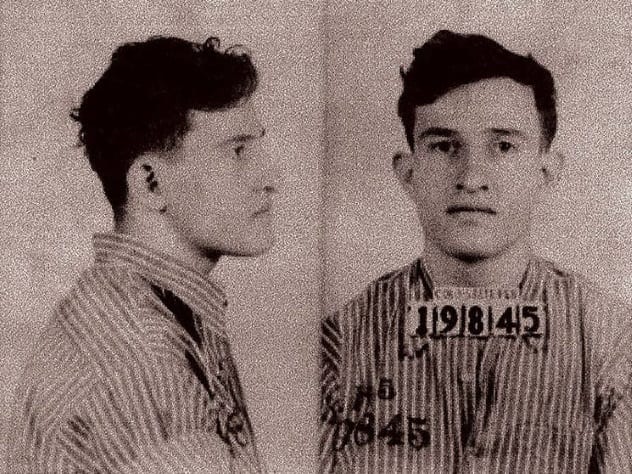

6 Joe Arridy

Joe Arridy had the mental capacity of a five-year-old and an IQ of 46. His greatest delight was playing with his toy trains and eating ice cream. In 1936, Arridy was said to have confessed to the brutal rape and murder of 15-year-old Dorothy Drain, as well as the rape and attempted murder of her 12-year-old sister. He was said to have bludgeoned them with a hatchet as they slept.[5] It is certain that Joe would not have understood what he was confessing to. He could not have read the statement that he signed. And it is certain that he was not mentally capable of the murders. However, he was held on death row for three years before his execution, where his favorite pastime was playing with his toy train. His last meal was ice cream. Joe Arridy was executed at the age of 23. A friend of the girls’ father, Frank Aguilar, later confessed to the crime. He had never even met Joe Arridy.

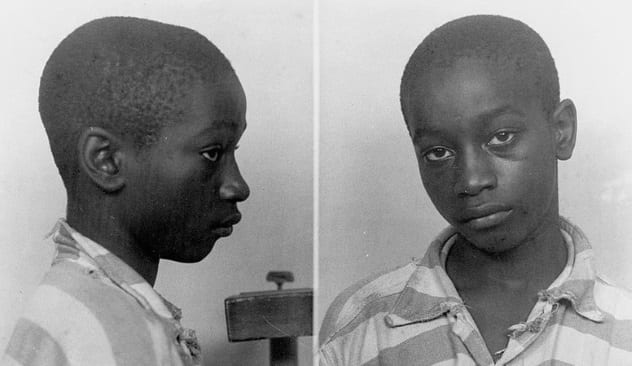

5 George Stinney

In 1944, George Stinney became the youngest person to be executed in the United States in the 20th century. Stinney was convicted of the murder of two white girls in South Carolina. The whole trial is said to have lasted less than three hours and presented no evidence and almost no eyewitness testimony. He was convicted by the all-white jury, after a deliberation which lasted only ten minutes. The 14-year-old was prevented from seeing family, friends, or legal counsel when he was interrogated, and it is claimed that he was so frightened that he would have said anything that the police asked him to. There was no evidence linking him to the dead girls, except that Stinney and his sister were the last people to see the girls alive. Stinney was arrested, tried, and executed all within the space of three months. He was too small to fit in the electric chair and had to sit on a Bible to enable the straps to be placed around him. His sister and the rest of his family campaigned tirelessly to clear his name.[6] In 2014, a judge vacated the conviction, stating that George Stinney had been denied a fair trial.

4 George Kelly

In 1949, a cinema manager and his assistant were murdered during a bungled robbery in Liverpool when a man burst into the manager’s office as the takings were being counted and shot them both. The gunman then fled, leaving the cash untouched. The police were under great pressure to solve the crime and had already interviewed 65,000 men when they received an anonymous letter that pointed the finger at George Kelly as murderer and another man, Charles Connolly, as lookout. At their first trial, the two men were tried together, and the jury failed to reach a verdict. The two men were subsequently tried separately, and Charles Connolly pleaded guilty to robbery and conspiracy. George Kelly continued to deny any involvement in the crime but was was convicted of the double murder and was hanged in 1950. In 2003, the convictions of both men were overturned, and the original verdict was declared “unsafe.” The original jury were never told that another man, Donald Johnson, had confessed to committing the crime. He had been arrested for the murders but released after the anonymous letter implicating Kelly and Connolly. The evidence of the confession was only discovered in 1991, when a member of the public who was researching the case was given access to the police files and found the statement about the confession. It was suggested that the police deliberately concealed this evidence.[7]

3 Thomas And Meeks Griffin

In April 1913, 73-year-old John Q. Lewis, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War, was murdered in his own home in South Carolina. Lewis was known to have had a relationship with a married black woman, and immediate suspicion fell on her husband. However, possibly in order to avoid scandal, it is claimed that the police did not thoroughly investigate the adultery angle, despite the fact that when officers went to question the husband, he was found with his bags packed and was wearing bloodstained trousers. Another man was arrested in connection with the crime. At first, he claimed to be acting as lookout while the cuckolded husband killed John Lewis. Later, possibly after persuasion from the police, Stevenson implicated Thomas and Meeks Griffin instead, on the promise of a reduced sentence. The Griffin brothers were the wealthiest black men in Chester County. They owned 138 acres of land and were popular in the community. It is believed they were implicated because they could afford a proper defense lawyer, and given that they were innocent, it was assumed they would be acquitted.[8] However, the trial judge was said to be hostile to the Griffin brothers, possibly due to their elevated position, their wealth, and their race, and after an extremely biased trial, the brothers were found guilty and executed swiftly. They were pardoned in 2009, the first posthumous pardon ever granted in South Carolina.

2 Teng Xingshan

In 1989, Teng Xingshan was executed for the murder of Shi Xiaorong. Xiaorong had disappeared one month before a dismembered body was found in a river in China and was identified as the missing woman. The dismembered body was said to have been cut in a “professional” way, and since Teng Xingshan was a butcher, he was suspected. It was further alleged that the two had had a sexual relationship and that Teng suspected Shi of stealing from him.[9] At his trial, it was said that Teng Xingshan had confessed to the crime “on his own initiative.” That’s odd, as four years after Teng’s execution, Shi Xiaorong returned to her hometown. She said that she had been swindled and sold as a “wife” in another province. In 2005, she urged authorities to undo Teng’s conviction. When asked about her relationship with Teng, she replied that she had never even met him. Teng was declared innocent in 2006.

1 Myles Joyce

In 1882, John Joyce, his mother, his wife, and his two children were brutally murdered in their home in Ireland. Maolra Seoighe (“Myles Joyce” in English) was one of ten men charged with the murders. The men were all due to stand trial, but then two of them made a deal to “identify” the perpetrators. Myles Joyce (of no relation to the victims) was one of the men implicated. Joyce spoke only Irish but was not given the services of an interpreter at his trial and never understood a word until the verdict, which was helpfully translated from English to Irish for his benefit. He was said to have protested his innocence, but in a language that the court could not understand. The jury considered the evidence for only six minutes before returning their guilty verdict. Two of the other convicted men admitted their guilt and stated that Joyce had had no part in the crime, but it was deemed to be too late to stop the execution. Myles Joyce was hanged in December 1882. As he was brought to the scaffold, Joyce said, in Irish, of course, “I will see Jesus Christ in a little while—he too was unjustly crucified.” The Irish parliament recognized that a miscarriage of justice had taken place and issued an unconditional pardon for Myles Joyce in 2018.[10] Ward Hazell is a writer who travels, and an occasional travel writer.