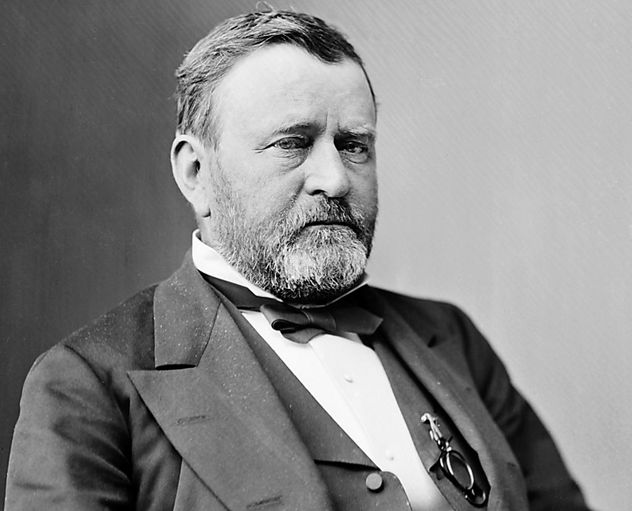

10Grant Wasn’t Always Considered A Hero

Grant’s bosses nearly arrested him in 1862. On April 16, 1861, just four days after Fort Sumter was attacked, Ulysses S. Grant volunteered for the army and quickly became a general under General Henry Halleck. These two men had very different leadership styles. As a result, Halleck frequently complained that Grant was insubordinate. Grant won important battles in February 1862, but General Halleck used a communications breakdown to complain about Grant to his boss, General George McClellan in Washington. McClellan wrote back, “The future success of our cause demands that proceedings such as Grant’s should at once be checked . . . do not hesitate to arrest him.” Luckily for everybody but the Confederacy, Halleck had cooled down by the time McClellan’s note reached him. He just removed Grant from command and kept him out of the loop until Halleck himself went to Washington to replace McClellan. Grant’s rise to the top began soon afterward, when President Lincoln told those who were asking him to fire Grant, “I can’t spare this man—he fights.”

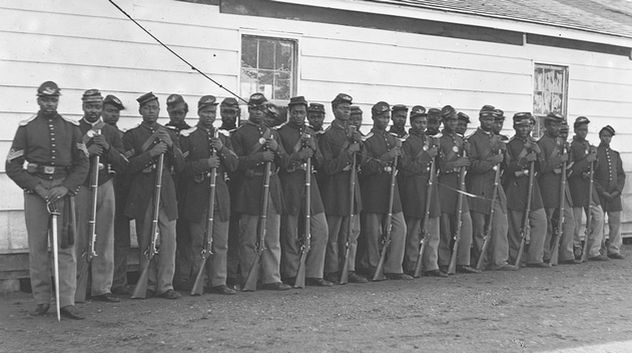

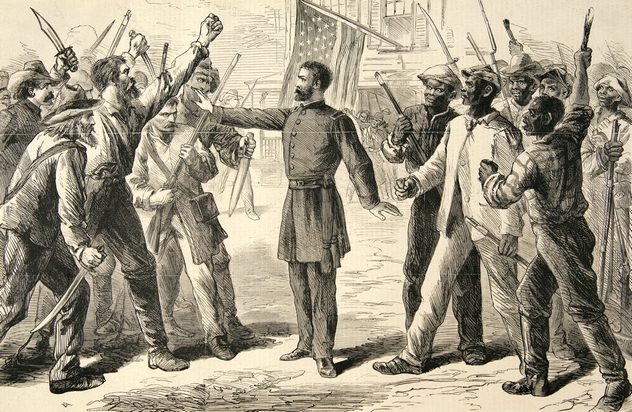

9The Glory Battle Wasn’t The First Time African-American Troops Went Into Battle

Glory is about the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the first African-American military unit to be raised in the North. It formed in 1863, the same year as the Battle of Fort Wagner. However, in October 1862—before either the Emancipation Proclamation or the Louisiana Native Guard’s charge at Port Hudson in 1863—the First Kansas Colored Volunteers fought and repelled Confederate cavalry at Island Mound, Missouri. The First Kansas unit was organized by local Union officials in August 1862, even though the US Army still refused to accept African-American troops. In late October, about 240 troops were sent to Bates County, Missouri, to break up a band of Confederate guerrillas. The First Kansas, outnumbered, took over a local farm and renamed it Fort Africa. After two days of fighting, they were reinforced, and the Confederates withdrew. The engagement was a minor one, but it received national attention and helped pave the way for African-American units like the 54th Massachusetts.

8The First Civil War Land Battle Wasn’t At Manassas (Bull Run)

The Civil War opened on April 12, 1861, when Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was bombarded. You might think the first battle fought on land was First Manassas (or Bull Run), when the citizens of Washington came out for a picnic in July and ended up running for their lives, along with US troops, in what the Southern press called the “Great Skedaddle.” You would be wrong. In June 1861, Union troops caught Confederate soldiers by surprise in Philippi, Virginia (now West Virginia). The Northern press called the undignified Confederate retreat the “Races at Philippi.” It was a small engagement with no fatalities, but it did have some interesting consequences. The US victory helped support the movement for secession in western Virginia. It also propelled George McClellan toward the coveted position of top general in Washington. Finally, a Confederate soldier named J. E. Hanger—an engineering student who lost a leg at Philippi—invented the world’s first realistic and flexible amputee prosthesis and went on to found today’s Hanger Prosthetics and Orthotics.

7The War Didn’t End At Appomattox

On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant at Appomattox. However, fighting continued elsewhere. General Joseph Johnston then surrendered the Army of Tennessee, the second-largest effective Confederate army, to General Sherman at Durham Station, North Carolina, on April 26. There were still soldiers in the field. On May 4, General Richard Taylor surrendered the 12,000 men serving in the Confederate Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. Then, on May 12–13, more than a month after Appomattox, the last battle of the Civil War took place at Palmito Ranch, Texas. General Kirby Smith, head of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, wanted to keep fighting afterward, but General Simon B. Buckner surrendered for him on May 26. On June 23, the last Confederate general, Stand Watie, surrendered in Indian Territory to US Colonel Asa C. Matthews. However, the war at sea went on until November, when the last Confederate commerce raider surrendered. Speaking of commerce raiders . . .

6The Civil War Wasn’t Restricted To US Territory

Confederate privateers (quasi-legal pirates) and commerce raiders on the high seas made life miserable for US shippers. Privateers and blockade runners kept Union blockaders busy in waters around Bermuda, the Bahamas, and Cuba. Big commerce raiders, powered by steam as well as sails, ranged all over the world, seizing US ships and ransoming their crews. The Union tried to stop them. For example, the USS Wachusett attacked the CSS Florida in Bahia Harbor, Brazil, causing an international incident. The USS Wyoming chased the CSS Alabama throughout the Far East but never caught it, although the Wyoming did engage Japanese forces in a side battle. The CSS Shenandoah started patrolling the sea routes between the Cape of Good Hope and Australia in October 1964, terrorizing the US Pacific whaling fleet. The ship continued operating long after the land armies had surrendered, taking 21 more US ships, including 11 in just seven hours in the Pacific near the Arctic Circle. The Shenandoah‘s captain and crew finally surrendered in Liverpool, England, on November 6, 1865.

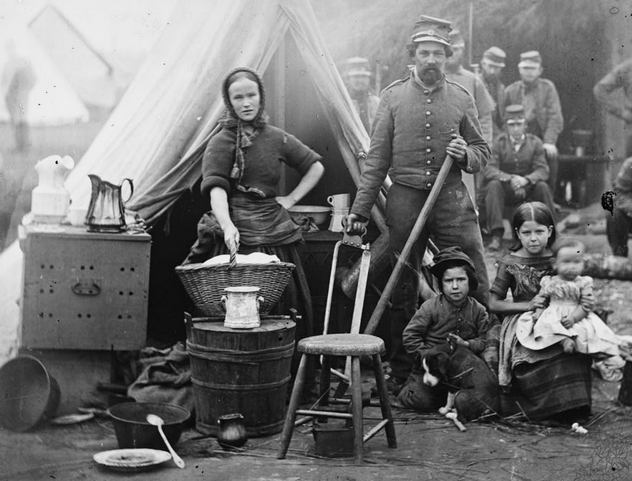

5Soldiers Saw Combat Only About One Day A Month

Back in the 19th century, thanks to dirt roads and lack of all-weather gear, armies had to plan their movements around the seasons. For most of the Civil War, at least up until the last desperate months of late 1864 and early 1865, weather factors divided the year into campaigning season—late spring, summer, and fall—and winter quarters. That’s why the average Civil War soldier only saw combat about one day out of 30 each year. The rest of the time he was marching, drilling, or just hanging around camp, where his life was still at risk. Primitive field conditions and lack of medical knowledge guaranteed that every soldier stood a one-in-four chance of not surviving the war, even without seeing combat. Less than a third of more than 360,000 Union deaths were combat-related; everyone else died of disease, mostly dysentery. Records for Johnny Reb aren’t as complete, but the percentage of non-combat-related deaths was roughly the same—almost two-thirds.

4The North Had A Hard Time Funding The War

We know the South had severe financial problems during the war, but so did the North. War is not only Hell—it’s expensive! The Union wasn’t prepared to fund a war. Lincoln’s election in 1860 had sparked turmoil on Wall Street. Worse, in the 1830s, President Andrew Jackson had done away with centralized banking, calling it “subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people.” There was no quick and easy way for the US government to finance its military buildup, especially not with over 10,000 different kinds of paper currency in circulation. With the help of Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln finally straightened out the mess enough to wage war, although Federal troops, particularly African Americans, sometimes went without pay for months at a time. One result of this was the first US federal income tax, which was passed in 1862. The Confederacy imposed its own government income tax in 1863.

3The War Was Fought With Basic Modern Weapons As Well As Firearms And Artillery

War today wouldn’t be possible without electricity and rockets. Chemical and biological weapons, while banned, are also used sometimes. Believe it or not, all of these combat technologies were also employed during the American Civil War. Floating containers filled with explosives, designed to sink ships, had been around since the American Revolution, but Confederates took it to the next level by adding electric detonators. They established what was probably the world’s first combat electric mine station in the Mississippi River. Electric mines had wires connected to the shore, which were used to detonate them. These weapons were also used in the Eastern Theater, where one sank the USS Commodore Jones in Virginia’s James River in May 1864. Rockets, which were gunpowder-propelled incendiaries, had been used during the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, and both sides also used them in the Civil War. The Union even had a 160-man rocket battalion. As we’ve already pointed out, incendiaries named after Greek fire—a chemical weapon—were used by both sides. The South also attempted biological warfare by infecting clothes with yellow fever (unsuccessful) and smallpox (limited success), as well as by poisoning water supplies with animal carcasses during a retreat.

2Some Slave Owners Fought For The Union

John Six-Killer was a Cherokee who served in the First Kansas Colored Volunteers. He fought and died in the aforementioned Battle of Island Mound. Ironically, he also was a slave owner and actually brought his slaves into battle with him. Slavery of African Americans was a common practice in the Cherokee Nation. The border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri also contributed men from slave-owning families to US military forces. Kentucky was especially important. Almost a quarter of Kentuckian families owned slaves at the beginning of the war, yet the state would send a total of 90 battle units to fight for the Union. That was why Abraham Lincoln only addressed the Confederacy’s slaves in his Emancipation Proclamation. The embattled US president knew that if he alienated Kentucky, he’d lose the rest of the border states and may as well have had to accept the Southern states as a new nation.

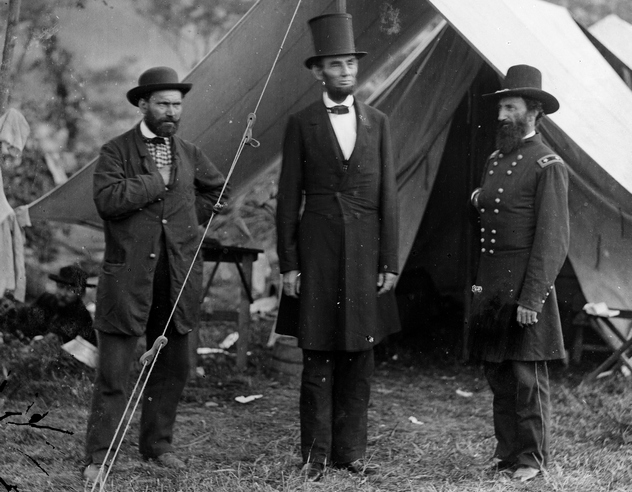

1Presidents Lincoln And Davis Didn’t Always Lead From The Rear

Today we tend to think of the US and CS presidents as valuable king pieces in a giant chess game. In fact, both men were present during battles. In 1862, for example, Jefferson Davis watched the bloody, inconclusive Battle of Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks) and gave Robert E. Lee command of the Confederate army afterward, as the two men rode back to Richmond. Abraham Lincoln visited Fort Stevens, outside of Washington, in 1864 and came under enemy fire. Confederate General Jubal Early said after the fight, “We didn’t take Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like Hell.” If so, it didn’t take. Lincoln visited General Grant’s headquarters on March 24, 1865, at a key point in the siege of Richmond. The president stayed there on a ship, close enough to the front to hear the gunfire, until Grant took Richmond. Then Lincoln went into town, entered the Confederate president’s office (Davis and his cabinet had fled), and sat down in Jefferson Davis’s chair. Honest Abe knew how to make a point. Barb blogs about the American Civil War and volcanoes at bjdeming.com. She also has published fiction about a US soldier and a Buddhist monk meeting on a Vietnam War battlefield.