10 The Cuxhaven Raid

The common story of Christmas 1914 is the Christmas Day truce, where soldiers on both sides stopped fighting to celebrate the holiday during World War I. While that was happening in the trenches, the British were conducting a historic airstrike on the German navy. Intelligence reports showed that Cuxhaven had zeppelin sheds, where the giant airships were being kept. From the start of the war, zeppelins had menaced the British. No fighter planes could catch the airships, and they flew unmolested over UK airspace. Thus, the Navy hatched their plan: If they couldn’t destroy the airships in the air, they would destroy them on the ground. Unfortunately, the sheds were out of range for ground-based airplanes. However, British commanders really wanted to raid the sheds, so they developed an imaginative plan to use sea-based airplanes. There was no such thing as an aircraft carrier at the time, but the British improvised. Using converted passenger ferries that could carry seaplanes, the British planned to move their naval forces as close to Germany as possible and then launch the seaplanes to bomb the zeppelin sheds. On the day of the raid, only seven airplanes were able to take off, but soon, the incredibly brave pilots were on their way to Cuxhaven. Even then, the weather didn’t cooperate. Heavy fog blanketed the sheds, and anti-aircraft fire stopped some of the attackers from getting close to their target. Nevertheless, all the British airplanes survived the attack. The pilots had to ditch in the sea and were picked up by British submarines and Dutch trawlers. The raid itself was not incredibly destructive, but it was a sign of things to come. By adopting new military tactics, the British proved that shipborne air attacks were possible, leading to further use of naval airplanes in World War I and later wars.

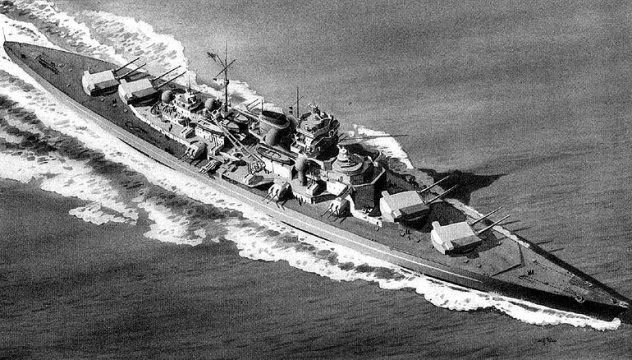

9 The Sinking Of The Tirpitz

Right before World War II, Nazi Germany built two gigantic battleships, the Bismarck and the Tirpitz. Both ships caused great concern for Allied forces and the British in particular. Throughout the war, British forces were constantly trying to sink the ships. In 1941, a combined bomber and surface ship attack sunk the Bismarck, but the first attacks on the Tirpitz were not as successful. For three years, the British tried to sink the Tirpitz. Carrier strikes conducted by the Fleet Air Arm proved ineffective against the giant battleship. The British became more and more desperate. After trying daring midget submarine attacks, the responsibility for sinking the ship transferred to Bomber Command in 1944. Fortunately, they’d just developed a new bomb called the Tallboy. The huge bomb weighed 5,400 kilograms (12,000 lb) and hit with just enough force to buckle battleship armor. Soon, Bomber Command hatched a plan to use the bombs to sink the Tirpitz. Since the Tallboy was so big, the only airplane that could fly the mission was the Lancaster bomber, which was usually used for high-altitude night bombings. For this mission, the bombers had to fly low during the day. Hitting the ship required precision flying and aiming. Flying from bases in the Soviet Union, Bomber Command conducted two unsuccessful attacks in the fall of 1944. Smoke screens and intercepting fighters ruined both missions. On November 15, a third mission launched. For most of the mission, 30 Lancasters flew 300 meters (1,000 ft) above the ground, under enemy radar. Then, as they approached the battleship’s mooring, the bombers quickly climbed to a bombing height of 3,600 meters (12,000 ft), which was necessary for the Tallboy to gain enough energy during its descent. The Tirpitz opened fire with everything it had, trying to shoot down the planes with its main guns. With the smoke screen inoperable, the bombers had a clear sight of the target. Three bombs hit and sunk the ship. Only one Lancaster was shot down.

8 Operation Opera

In the late 1970s, the Iraqi government purchased a nuclear reactor from the French. While both countries claimed that the reactor was purely for scientific research, Israel was more suspicious. Having a nuclear reactor in the region was a big concern. Early 1980s intelligence estimates believed that Iraq would have nuclear weapons within the decade. Quickly, the Israelis attempted to seek a diplomatic solution to their problem by trying to convince European powers to stop funding the reactor. Diplomacy failed, so the Israeli military began to plan a daring strike against the reactor without consulting other nations. Israel would use US-built F-16s and F-15s for the attack. Engineers stripped down eight F-16s to carry as many munitions as possible. The F-15s would provide air support. Overall, the mission would require the jets to fly 1,000 kilometers (600 mi) over three enemy countries. For most of the mission, the fighters would fly only 46 meters (150 ft) off the ground. On June 7, 1981, the attack force took off. Their flight took them over Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and then Iraq. Careful planning gave the fighters a path that avoided ground-based radar and enemy airfields. Even though the planes were so close to the ground, nobody knew they were coming until they got to Iraq. King Hussein of Jordan was visiting Iraq that day and saw the low-flying jets screaming overhead. He quickly tried to get a warning to the Iraqi military, but it was too late. The F-16s dropped their bombs and annihilated the reactor. They then climbed to 12,000 meters (40,000 ft), flew over Jordan, and returned home. The reactor was gone, which stopped any hopes that Iraq had of nuclear power or weapons.

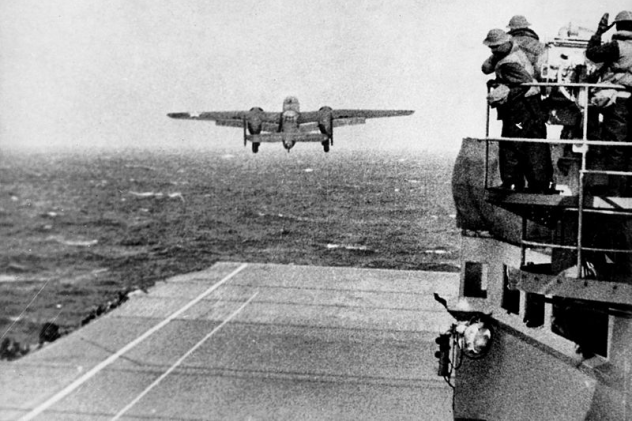

7 The Doolittle Raid

One of the most famous air raids conducted by the United States during World War II, the Doolittle Raid is a mission that most people have heard of but don’t realize how absolutely insane it was. The raid was a retribution for the attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the US into World War II. Military planners wanted to conduct a retaliatory air raid, but the only problem was that they didn’t have airplanes with a long enough range to hit the Japanese home islands. Hotshot pilot Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle had an idea: Launch ground-based medium bombers from a carrier on a one-way strike over Japan. Training of volunteer bomber crews started immediately. The B-25 bombers used for the raid usually needed 360 meters (1,200 ft) of runway distance, but the aircraft carrier USS Hornet only had a 150-meter (500 ft) deck. Eventually, the crews figured out how to take off in that distance. To make it work, the B-25s had to cut as much weight as possible. All unnecessary equipment left out of the planes. On April 18, 1942, the mission commenced earlier than expected. The carrier group made contact with Japanese picket ships. Although escort ships sunk the Japanese pickets, the surprise was lost. The mission launched 10 hours earlier than expected and 270 kilometers (170 mi) further away from Japan than planned. Doolittle’s B-25 took off first. His bomber’s job was to fly alone over Tokyo and mark the targets with incendiary bombs. An hour after Doolittle left, 15 other bombers took off, each barely making it off the aircraft carrier. Roaring in at 600 meters (2,000 ft), the bombers attacked Japanese industrial targets. After they dropped their bombs, the B-25s were too fast for intercepting Japanese fighters to catch them. [11] Then came the really dangerous part—landing in Japanese-occupied China. Most crews touched down in China and met up with local resistance leaders. One crew landed in the Soviet Union and got interned. Eight crew members were captured by the Japanese, and three were executed. Overall, the mission did minimal damage, but it boosted US morale while crushing the Japanese leadership.

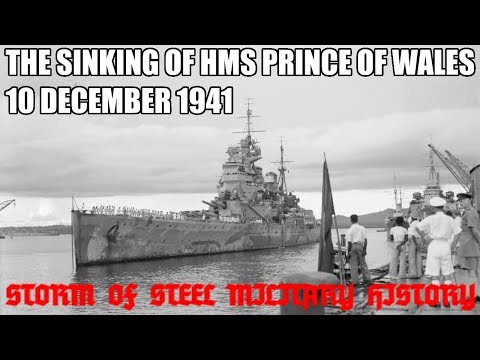

6 The Sinking Of The Prince Of Wales And The Repulse

Often forgotten in comparison to Pearl Harbor, the sinking of two British battleships, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, was the other major Japanese air raid in December 1941. That month, the British Force Z started to sail toward Malaya to stop a Japanese invasion fleet. However, the force’s commanders made terrible tactical choices. They elected to sail without air cover of any kind so they could have complete radio silence. This fateful decision doomed the fleet. Although they were sailing without air cover, the sailors were confident in the ships’ anti-aircraft defenses. Japanese forces spotted Force Z and quickly made plans to attack. Unlike Pearl Harbor, this attack would be much more difficult, since the ships could maneuver in open water. Never before had the Japanese conducted a bombing attack on ships in open water. To make sure that the ships were hit, the Japanese launched 85 aircraft to attack the force. G3M medium bombers carried out the main thrust of the attack, even though they weren’t specifically designed for attacking battleships. On the first attack run, the bombers hit the support ships with armor-piercing bombs but failed to sink them. However, the second wave of G3Ms were carrying torpedoes. These bombers came in at extremely low altitude, flying straight into British anti-aircraft fire, as was necessary for a torpedo bomber collapse. Wave after wave came in, and eventually, both the Prince of Wales and the Repulse took four torpedoes each, sinking them. Even though the Japanese pilots had never conducted an attack like that, they were extremely successful. Only 18 Japanese aviators were lost, while 840 British sailors died.

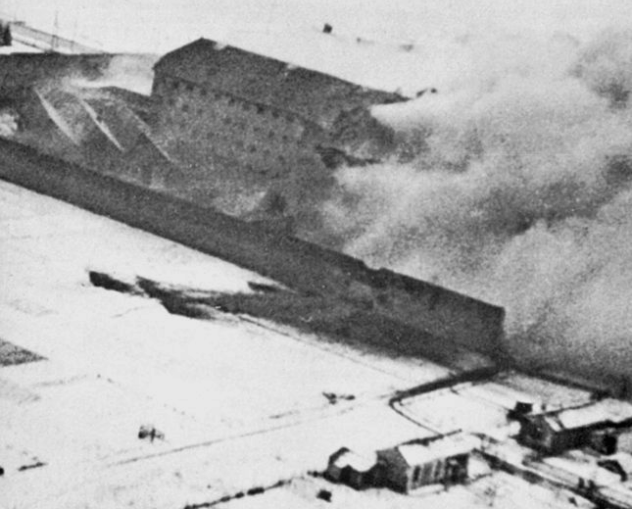

5 Operation Focus

In 1967, Israel’s neighbors began to build up their militaries to attack the small state. Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Jordan were the primary allies against Israel. Each had a sizable air force that could decimate the Israeli forces quickly. With Israel facing a war against several countries, military planners realized that the only way to turn the upcoming conflict in their favor was to conduct a preemptive airstrike against their enemies’ combined air forces. Known as Operation Focus, this airstrike was one of the biggest in recent history. Israeli pilots mostly flew French Mirage fighter planes loaded with bombs. Nearly 200 aircraft lifted off on June 5. This huge strike force constituted the majority of the Israeli air force. Only a few interceptors stayed behind to patrol friendly airspace. It was quite literally an all-or-nothing attack. On the first wave, the Israeli pilots hit 11 Egyptian bases, catching most of the Egyptian airplanes on the ground, unable to respond to the attack. After the first wave, the Israeli pilots returned to base and were reloaded with bombs, taking off again in under 10 minutes for the next wave. When the second wave was successful, the pilots conducted one more attack, once again reloading and refueling in less than 10 minutes. All of these attacks occurred in the space of three hours. In the end, 500 Egyptian, Syrian, Iraqi, and Jordanian planes lay burning on the ground, decimated by the Israeli strikes. Israel took minimal losses of only 19 airplanes. With the coalition air force destroyed, Israel maintained air superiority for the rest of the Six-Day War.

4 The 1943 Mosquito Raid Of Berlin

As World War II dragged on, the Royal Air Force became more bold in their attacks on Germany. Before 1943, the RAF was unable to bomb Berlin due to a lack of suitable aircraft as well as the city’s strong anti-aircraft defenses. By 1943, however, the Nazi forces were weaker, and the British had a new bomber. The de Havilland Mosquito was a beautiful plane made of wood. The plywood bomber was absurdly fast, capable of outrunning any German interceptor. They were perfect for the opening bombing raids on Berlin. On January 30, the Nazis were preparing for a big event celebrating 10 years since Hitler came to power. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and Luftwaffe head Herman Goering planned to deliver celebratory speeches over the radio. Allied intelligence learned exactly what time the two men would be delivering their speeches and planned to disrupt them with a Mosquito attack. At 11:00 AM, Goering got up to give his speech, only to find bombs falling from overhead. The first Mosquito element successfully bombed the area in which Goering was giving his speech, and the Luftwaffe head was unable to take the lectern for an hour after the attack. He was said to have been “boiling with rage and humiliation.” Five hours later, Goebbels got ready to give his speech, only to be disrupted by another Mosquito attack right as he was starting. Only six aircraft conducted the attacks, but they managed to be a huge embarrassment to the Nazi leadership. Later that night, the first British bombing raid using radar successfully took place. These cheeky missions started the two-year bombing campaign against the German capital.

3 Operation Jericho

Another amazing raid conducted by Mosquito bombers was Operation Jericho, the attack on Amiens Prison. The Nazi prison was known to hold 700 Allied aviators and French resistance operatives. The prison had high walls and guard shacks, which made it impossible to attack from the ground. Bombers were the only option. But since there were prisoners inside, the bombers couldn’t simply blow up the buildings. Military engineers developed precision bombs that could be dropped from low altitude and use delayed charges to blow up the walls of the prison without killing the inmates. In theory, the destroyed walls would allow prisoners to escape out into the countryside. With the operation planned for February 1944, the mission planners had to wait for the winter weather to clear up. Day after day passed of bad weather until the February 18, when they decided to launch the strike regardless of the weather. Eighteen Mosquitos took off into terrible weather, which forced some members of the strike force to turn back. However, enough made it to the target to start the attack. Some Mosquitos dropped bombs on the guard housing, while others used their special bombs to destroy the walls, all while flying only 15 meters (50 ft) off the ground. Bombardiers needed absurdly precise aim to not hurt the prisoners. Well-placed strikes breached the walls, but some prisoners were caught in the explosions. Nevertheless, many prisoners escaped through the breached walls. Oddly, this mission is quite controversial. Historians debate whether the prisoners were actually in danger while in the prison and question the usefulness of the attack. Still, the idea of bomber planes flying barely above the ground to knock holes in walls is pretty impressive.

2 Operation Chastise

Germany’s Ruhr valley was heavily industrialized during the war and was a main source of the country’s war-making ability. There were several large dams that provided hydroelectric power for factories. British planners knew that they needed to come up with a way to destroy the dams, but they realized that traditional bombing raids would take a huge amount of bombers and would be extremely dangerous for pilots. Engineer Barnes Wallis had a different idea. Wallis developed a strange bouncing bomb. The cylindrical bomb was spun right before being dropped by Lancaster bombers. When the spinning cylinder impacted the river surface, it would bounce on the water, crash into the dam, and then sink to the river floor, where it would explode. With this technique, the bomb would avoid the anti-torpedo nets defending the dams and cause maximum damage by hitting their bases. To make it work, the Lancaster crews would need to fly extremely low and to drop their bombs at the right time. Wallis developed a special targeting device shaped like a V. The bombardier would look down the V while the bomber approached the dam. When the two points of the V lined up with the towers on the dam, the bombardier would drop the bouncing bomb. Special spotlights on the bottom of the bombers told the pilot how high he was. When the spotlights touched on the ground, he was at the ideal height of 18 meters (60 ft). On the night of May 16, 1943, 19 Lancaster bombers from the No. 617 squadron took off to conduct the attack. From the beginning, the raid was incredibly dangerous. To avoid radar and flak, the bombers flew low over the English Channel and over the European coast. The force split into two attack waves to hit the dams, but they began to lose planes to both flak and difficult flying before they even reached the target. Nevertheless, most of the planes made it and conducted their bombing runs, flying just above the water while flak pounded around them. No. 617 squadron successfully breached two dams during the attack and damaged one. Close to 1,600 people on the ground died in the attack, mostly prisoners of war. In all, eight of the 19 aircraft didn’t return to base. From that time forward, No. 617 squadron was known as the Dam Busters.

1 Operation Tidal Wave

During World War II, the oil fields of Ploiesti, Romania, accounted for 30 percent of Axis oil production. Allied planners knew that taking the oil fields out would significantly cripple the Axis war effort in Europe, so they hatched a plan in 1943 for the United States 9th Air Force to conduct a daring mission to destroy the fields. The only problem was that Ploiesti had one of the best air defense grids in Europe. Mission planners realized that the bombers would have to fly at extremely low altitude to get under the radar coverage, but that would expose them to the countless anti-aircraft guns around the oil fields. Still, it was a risk that the Americans were willing to take, and they committed 178 bombers in five strike waves, the largest strike up to that time. All of the airplanes were B-24 Liberator bombers, big four-engine heavy bombers designed for high-altitude missions. Flying from Benghazi, Libya, the five strike waves took off on August 1. The plan was for all five groups to attack at the same time, but issues quickly arose. In one group, a bomber dropped into the sea, almost causing a midair collision. In other groups, the pilots used the wrong power settings for their engines and fell behind. What was once a cohesive strike force became a strung-out formation of bombers. The mission was further exasperated by navigational issues. Worse still, the Germans knew they were coming. They alerted their defense grid and launched 200 fighters to meet the American bombers. The first wave of attack commenced with two groups swooping down at low altitude to hit the oil fields. While they flew away from the fields, the other groups started their attacks, having to fly through smoke and fire to find alternate targets, all while dodging alerted German defenses. Bombers flew so low that they were blowing thatch roofs off houses and dueling with German flak emplacements. The scattered American aircrews tried to make their way home to Benghazi, but many had to find alternate bases or try to seek sanctuary in neutral Turkey. In the end, a huge number of the planes were lost. In all, 310 airmen died, and 108 were taken prisoner. Within a few months, the oil fields were back at normal production capacity. The mission was a failure, but it was the most insane raid conducted by the United States during World War II. Zachery Brasier writes stuff.