SEE ALSO: 10 Incredible Accomplishments That Ruined Their Creator’s Lives

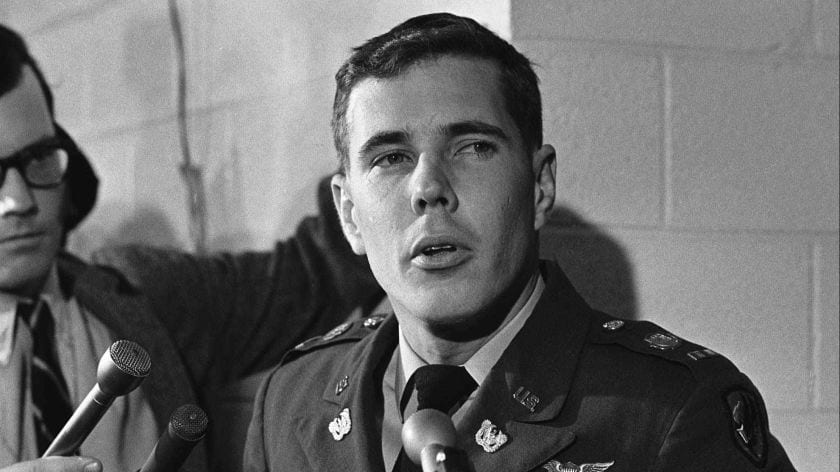

10 Hugh Thompson

The My Lai Massacre was an era defining black-mark on American history. Faced with the realization that the American military was indiscriminately killing entire Vietnamese villages for no tactical reason, the general opinion of the war began to shift. For Major Hugh Thompson Jr., that shift came too late. On March, 16, 1968, Major Thompson was piloting his helicopter when he heard artillery fire below. Flying down to help, he and his crew were shocked by what they found. Ordered to kill every Vietnamese person in sight, the American military gunned down 504 citizens. 210 of the casualties were under 12 years old. 50 were under 3. Going against all his training, Thompson did the unthinkable. He landed his helicopter and drew his guns on his fellow soldiers. He promised that if American forces killed any more civilians, he would have to fire on his fellow soldiers. The troops stopped. The carnage was over. Thompson and crew evacuated as many of the wounded as they could. Returning to base, Thompson reported the incident to senior officers. Future missions were cancelled, sparing potentially hundreds from more similar massacres. Nobody at the time considered Thompson a hero. Some still do not. Summoned to Congress to answer for his response, representatives berated Thompson. Congressmen suggested that Thompson should be court-martialed. The public similarly hated him. His phone continually rang with death threats. Bodies of mutilated animals showed up on his porch. For 30 years, the Army refused to acknowledge Thompson’s service. Eight years before his death, Thompson finally received recognition in the form of the Soldier’s Medal.[1]

9 Joseph Goldberger

In the early 20th Century, the Southern United States had a problem. Pellagra swept the region. 3 million people were diagnosed with the deliberating disease. The symptoms are drastic. Victim’s skin falls off. They become insane. As nearly 100,000 of them did, they eventually die. Joseph Goldberger left New York to put an end to the suffering. He was stopped by the other great epidemic of the South, racism. Today, pellagra’s cause has been well established, a dietary deficiency of nicotinic acid. Doctors at the time had no idea. Citizens in the 1910s were warned that the disease was spread person to person. Goldberger’s experiments exposed the disease’s link to poor diet. Promising early release to anybody who volunteered, Goldberger fed prisoners plates of corn, biscuits, rice, and yams. These foods were chosen, because of their popularity in the agrarian South. Within two weeks, the patients reported the first signs of pellagra. Upon switching to a nutritious diet, the subjects were back in good health. Even with clear evidence, southerners rejected the idea. Both Jewish and a Yankee, Southerners did not like the idea that Goldberger was saying the Southerner lifestyle was killing people. Goldberger had to take drastic steps to convince the naysayers. In 1916, Goldberger developed “filth parties”. He, his wife, and 16 other volunteers, purposely injected themselves with blood from pellagra patients. If that was not gross enough, he took the test further by eating cakes mixed with the skin, snot, urine, and feces of pellagra patients. Even after eating poop, people still refused to listen. Goldberger continued to push for his interpretation until his death in 1929. Pellagra won’t be cured in the South until the late ’40s.[2]

8 Buzz Aldrin

In July of 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin did something no other person in history ever had. Fulfilling the dreams of millions is a heavy responsibility. Aldrin did not know how to handle his role in one of humanity’s greatest achievements. Much like the lunar surface itself, Aldrin felt “magnificent desolation.” Nothing on Earth could compare. Touring around the country, Aldrin was exhausted by all the publicity and photo ops. He only wanted to get back to work. There was just nothing left to do. The Space Race had reached the finish line. Dejected, Aldrin spent many days refusing to get out of bed. He only got out of bed to grab another drink. He sometimes went to other people’s beds too. Searching for any form of excitement, he routinely cheated on his wife, Joan. In July 1971, Aldrin returned to work as a test pilot. His despair was not staved off for long. Now racked with back and neck pain, his alcoholism and listlessness increased. 1974 was Aldrin’s darkest days. Shortly after Aldrin’s father died, he and his wife divorced. A few months later, he married his then girlfriend, Beverly. The marriage was an immediate failure. The only constant during this time was his alcoholism. Too drunk to speak, Aldrin could no longer show up to engagements. In a drunken rage, he smashed his other girlfriend’s door. The police arrested the national hero. Aldrin hit rock bottom. Beverly and him divorced in 1978. He swore to turn his life around. In October 1978, Aldrin had his last drink. He signed up for Alcoholics Anonymous. After 12 small steps for a man, he made one giant leap. He has been sober for more than 40 years.[3]

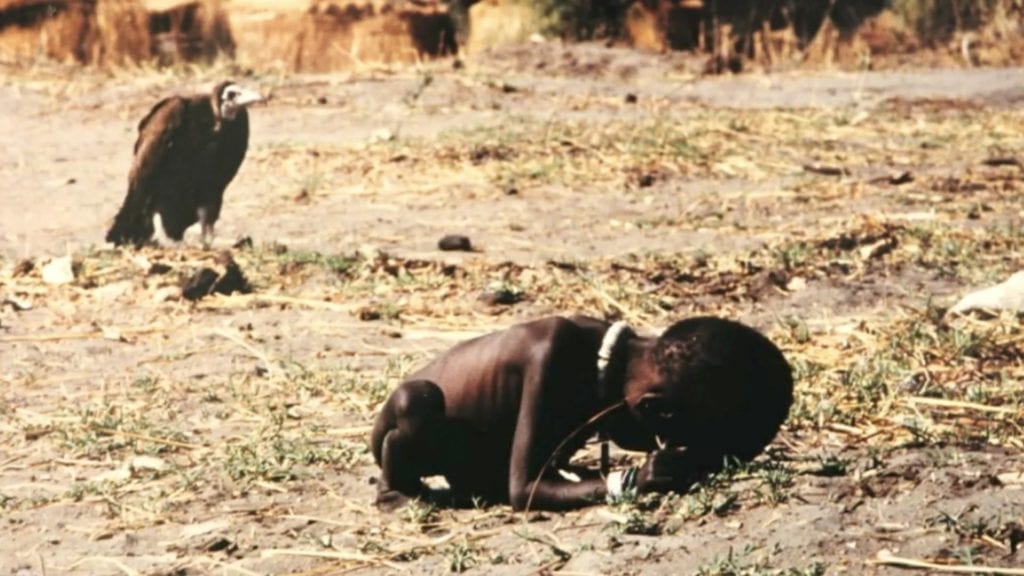

7 Kevin Carter

Death haunts the photo. A black vulture skulks a small child. Nearly unable to move, the infant crawls towards food relief. Visible bones protrude under the skin. The vulture and viewer know the end is imminent. For the child, it might have been. For the photographer, it definitely was. A life surrounded by chaos, Kevin Carter started his career documenting racial unrest, war, and riots in South Africa. His most famous picture captured a similar disaster. “The Vulture and the Little Girl”, otherwise known as “The Struggling Girl”, is one of the most recognizable pictures of all time. Capturing the bleakness of the 1993 Sudanese Famine, Carter’s image brought mass awareness to the hunger. As publications ran around the world, so did donations. Praised both for the quality of his camerawork and his humanitarian efforts, Carter won the Pulitzer Prize. Success attracted plenty of critics. At the Pulitzer reception, some audience made their complaints known. South African journalist wrongly believed he staged the shot. Others blamed Carter for not doing enough to stop the girl’s suffering. Carter had already blamed himself for that one. His depression started when he clicked his camera. The ultimate fate of the photo’s subject is unknown, but Carter could not shake the belief that he could have saved her. These thoughts followed him as he watched policemen execute protestors and again when he heard his friend Ken Oosterbroek was murdered. His life and career began to slip. His relationship with his long-term girlfriend fell apart. Absentmindedly, he routinely abandoned reels of film in random locations. He no longer cared about photography. His only interest was a drug called “white pipe,” a mix of marijuana and tranquilizers. It was all he had left. Two months after winning the Pulitzer, he was dead. He parked his pickup truck next to a small river. He attached a hose to pump exhaust into his front window. He was 33.[4]

6 Chiune Sugihara

Patriotism takes a lot of forms. While the Germany and Japan forces worked together to carve the world between the two great invasive empires, a Japanese diplomat was undermining the German war machine from within. Stationed in Lithuania, Chiune Sugihara felt compelled to betray both his homeland and government station for the greater good. It cost him everything. Shortly after the outbreak of the World War II, Sugihara issued transit visas to thousands of Jewish refugees. Tokyo specifically forbade him from issuing any more. A cable from the foreign ministry said that any more visas are “absolutely not to be issued to any traveler… No exceptions.” Sugihara moved his operations underground. Night and day, Sugihara and his wife, Yukiko, forged thousands of visas until his “fingers were calloused and every joint from [his] wrist to [his] shoulder ached.” Forced to flee the country, Sugihara was still throwing out formatted visas as his train left the station. The exactly amount of Sugihara saved from Hitler’s gas chambers is unknown. Conservative estimates believe it was at least 6,000. Sugihara did not get a hero’s welcome when he returned to Japan. His supervisors were aware he directly defied their orders. Because Sugihara still followed the Samurai Code, he was heavily criticized for disobeying his commands. It did not matter how many people he rescued. He was fired and dishonored. Ostracized from society, his family lived in poverty as he struggled to find work. Japan did not officially honor him until 2000, 14 years after his death.[5]

5 Oliver Sipple

Luck is a fickle thing. In a second, a life can be ruined. In another, a life can be saved. On September 22, 1975, two lives were forever changed during that tiniest window. Oliver Sipple had no intention of becoming a celebrity. All he wanted to do was walk down a street. On his stroll, he happened to see president Gerald Ford. Lurking among the crowd converged around the Commander in the Chief, Sarah Jane Moore pulled out a .38 caliber revolver. Unfamiliar with this particular gun, Moore’s shot grazed six inches from the president. Raising her hand to fire again, Sipple, a former marine, tackled Moore and wrestled the gun away from her. The Secret Service commended Sipple for his courage. Media outlets threw Sipple reluctantly into the spotlight. This was a great opportunity for the burgeoning gay rights movement. Harvey Milk and other gay activists saw Sipple as a national hero. This was a perfect opportunity to use Sipple’s story to dismiss stereotypes of gay men as cowards, weak, or not masculine. Without consulting Sipple, Milk outted him to the San Francisco Chronicle. Sipple tried to make the newspaper squash the story. It was too late. Everyone knew Sipple was gay, including his parents. Once the news broke, Sipple’s family abandoned him. His mother told him to never speak to her again. His father told his brother to forget that Oliver was his brother. Sipple was forbidden from attending his mother’s funeral. Rejected, Sipple turned to alcohol. Coupled with schizophrenia, Sipple’s mental state fell apart. During drinking sessions, he often wished he had never stopped Ford’s assassination. In late January of 1989, Sipple had his last drink. He died with only a Jack Daniels for company. 10 days later, his body was found. He was 47.[6]

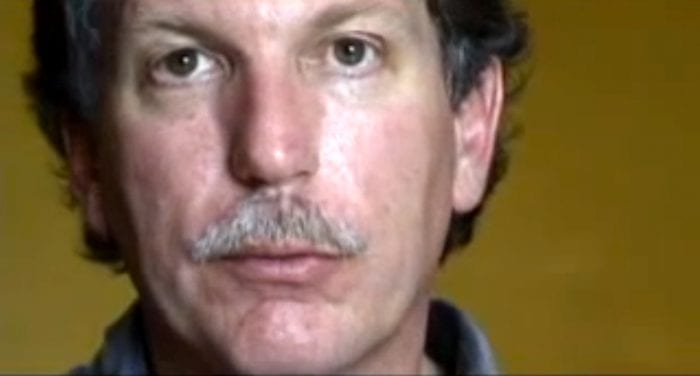

4 Gary Webb

Gary Webb’s status as a hero is still debated. Many think he was too reckless with the facts to be venerated. Supporters hail him for uncovering one of America’s most destructive episodes of deep state corruption. Both sides can agree he did not deserve such a disastrous downfall. Titled The Dark Alliance, Webb’s 1996 report exposed how Contra rebels in Nicaragua turned their support from the CIA into cocaine shipments into the United States. The market converted these deliveries into crack. Proceeds from the sales funded the Contras. As the drug ravaged primarily African American communities, the CIA did nothing to stop it. This report did not assert the CIA knowingly targeted black populations, nor did it allege any CIA planning. It merely said that the CIA was aware of this policy and let it continue. The Dark Alliance is not a perfect piece of exposé journalism. Evidence was scant for a narrative so bold. Accompanying graphics suggested a definitive tie between the CIA and the crack epidemic that the story itself did not charge. The stories real power was forcing a public outcry. Congress had to respond. Senators led by John Kerry created a panel to investigate the claims. Most of them were substantiate. Other government officials took a different response. Working in tandem with the CIA, mainstream newspaper outlets like the New York Times and Los Angeles Times challenged Webb whenever they could. Follow up stories targeted Webb personally and outright lied about some of his claims. The San Jose Mercury, where Webb worked, initially supported him. They backed off following other columnists’ comments. Nobody in the journalism world respected him. Professionally and personally, Webb was alone. In 2004, Webb shot himself in the head. Not above insulting a dead man, the Los Angeles Times obituary called him a “discredited reporter.” They did not acknowledge the role they played in his death.[7]

3 Robert O’Donnell

For 58 hours, a nation held its breath. A small hole in a West Texas backyard transfixed America. On October 14, 1987, 18-month-old Jessica McClure fell 22 feet down a well. Death seemed inevitable. By the next day, a media circus drew focus onto Baby Jessica’s precarious situation. Thousands of paramedics, police officers, and media personnel may have helped the infant, but it was firefighter Robert O’Donnell that emerged from the ground swaddling the young girl. America turned their love for Baby Jessica into praise for Robert O’Donnell. Awards and plaques swarmed O’Donnell. Parades in Midland and across Texas were thrown in his honor. He appeared on television shows like “G.I. Joe Search for Real American Heroes” or “3rd degree.” Both the Vice President and Oprah Winfrey came down to meet him. In the winter of 1987, O’Donnell could claim to be as big a star as either of them. Between October 14 and 16, Midland, Texas had America’s attention. It never would again. That is why Robert O’Donnell’s story went the route it did. He knew he deserved fame. No one else agreed. Co-workers snidely referred to him “Robo-Donnell” for his unwillingness to talk about anything besides his daring exploit. As book deals and movie rights dried up, he had continuous migraines. Prescription painkillers quelled the symptoms of the headaches, not the cause. His stomach bled from excessive pill consumption. He slurred his words until he was unintelligible. Excessive medication cost him his marriage and his job. Losing both of those cost him his life. In 1995, he put a shotgun in his mouth. He was 37 when he pulled the trigger.[8]

2 Gareth Jones

Of all the deaths attributable to the Holodomor, Gareth Jones’ is among the weirdest. Recognized now as man’s worst genocide, the Soviet Union’s Communist manufactured famine in the Ukraine killed more than 10 million people. Few at the time could believe the scale of Joseph Stalin’s horrors. The only person who did was Gareth Jones. In the summer of 1931, the Welsh journalist was deployed to Ukraine. Western reporters could not understand how the Soviet Union was modernizing in the height of the Great Depression. In a twist of history, Jones’ companion in his tour of mass hunger was HJ Heinz II, the heir to the food magnate. An eyewitness to the death toll, Jones’ diaries are the first public use of the word “starve” in relation to the Holodomor. Feeding them when he could, Jones captured the stories of citizens who would die before they could get the chance. In March 1933, Jones returned and published the article that exposed the truth to the world. Nobody wanted to hear it. In the article entitled, “Russians Hungry but not Starving,” New York Times reporter Walter Duranty dismissed Jones testimony. A strong Stalin supporter, Duranty purposely minimized the crimes of communism. Despite personally seeing the suffering, Jones was discredited as a sensationalist. While Jones was ostracized, Duranty’s report won a Pulitzer for his report. Barred from entering the Soviet Union, Jones toured Asia in 1934. In Japanese-occupied China, pirates kidnapped Jones and his companion. 16 days later, the bandits shot Jones the day before his 30th birthday. Evidence suggests this was just a cosmic injustice. Others believe the Soviet Union orchestrated Jones’ assassination for revealing their human rights violations. No matter the truth, Jones’ sacrifice is just one more sad detail in an already heartbreaking tragedy.[9]

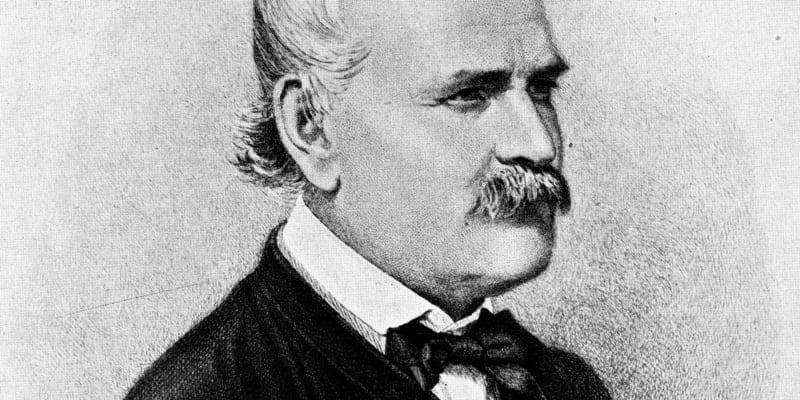

1 Ignaz Semmelweis

It is remarkable such a simple idea was controversial. Early germ theory pioneer Ignaz Semmelweis had a genius breakthrough, people should wash their hands. For that idea, he paid with his life. In 1847, Semmelweis served as the head of the maternity ward of Allgemeine Krankenhaus. The Viennese hospital was in dire condition. One in six women died after childbirth from a strange phenomenon known as “childbed fever.” Immediately after delivering a healthy child, women somehow contacted a deadly fever after. The new mothers’ uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes swelled with puss. Accepted theories of time include cold air getting into the vagina or that the expecting mother’s breast milk curdled in the vagina. Yet, Semmelweis’ ideas were considered the crazy ones. Semmelweis noted that the death rate was significantly higher if the birth was performed by a doctor. Rushed for time, doctors occasionally performed autopsies shortly before tending to pregnant mothers. Unaware of the concept of germs, Semmelweis believed that the doctors were subconsciously transmitting something from the cadavers to the delivery room. Enacting forced sanitization before entering the maternity ward caused the mortality rate to fall by 93%. Despite the obvious success of the practice, doctors were outraged by Semmelweis’ theory. They refused to believe that they were causing their patients to die. With no current scientific explanation supporting the policy, the medical community rejected Semmelweis. Out of work, he felt deserted. This triggered mental unrest. In 1865, he was admitted into an asylum. Later that year, guards beat him to death. Wash your hands today in his honor.[10]