Sometimes the world moves on far too swiftly to the next tragedy, leaving memory only in the minds and hearts of those most affected; sometimes even survivors wish to forget the painful past; and sometimes disasters are deliberately minimized or suppressed. Against these tendencies stands the principle that the best honor that can be given to the lost is the privilege of memory. Read on, then, and remember . . .

10 The Rana Plaza Collapse

The deadliest structural failure accident in modern history occurred in April 2013, and you’ve probably never heard of it. The infamous Boston Marathon bombing occurred the week before and garnered much media coverage with its three deaths and hundreds of wounded. But the collapse of this Bangladeshi building was a tragedy on a different order of magnitude: 1,134 people were killed, with more than twice as many injured. Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, was home to the Rana Plaza structure, originally constructed to contain shops and offices. Yet multiple upper floors were added on, without a permit, in order to house the heavy machinery for multiple clothing factories. These factories manufactured goods for such prominent brands as Benetton, Prada, Gucci, and Versace and employed around 5,000 people. Few, if any, of them knew they were working in a top-heavy death trap. Occupants of the building noticed cracks in the walls, ceilings, and floors on April 23, and the building was evacuated. Yet the building’s owner declared the structure safe and urged workers to return the following day. The shops and bank on the lower floors refused and remained closed, while the garment company managers threatened to dock the pay of any workers who failed to clock in. Just before 9:00 AM the following morning, the entire structure failed, disintegrating into a pile of ruin that an eyewitness compared to a one-building earthquake. More than 3,000 people were in the building at the time, including garment workers, support staff, and children in the companies’ in-office nurseries. Some died instantly, while thousands more were entombed in the rubble. The governmental reaction was mixed. Local emergency services responded as best they could, rescuing hundreds from the wreckage, and the government declared a national day of mourning on April 25. Yet there was also bureaucratic face-saving at work. UN offers of help were rejected by officials leery of negative international exposure.[1] Volunteer rescue workers were ill-equipped and ill-led. The work dragged on. The last survivor, seamstress Reshma Begum, was not pulled out until 17 days later. The tragedy lives on in the minds of Bangladeshis and certain international watchdog organizations, even though it has gotten little sustained attention elsewhere. Garment workers in the nation have protested substandard safety practices and low wages, though these protests have in some cases been violently suppressed. The owner of the building, Sohel Rana, is still awaiting judgment on multiple charges of murder.

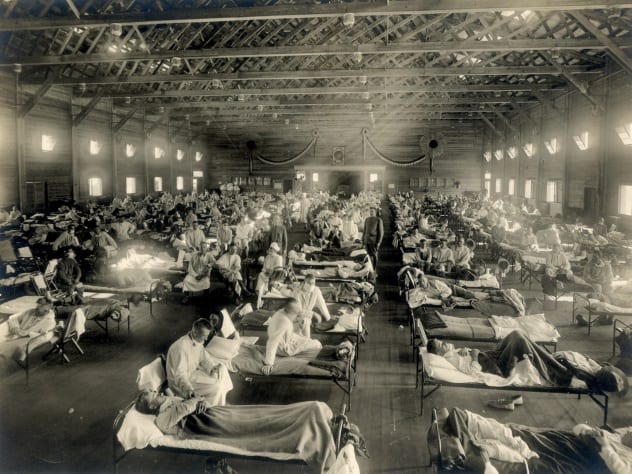

9 The Spanish Flu

It seems absurd to describe a worldwide pandemic with a 50 million-plus death toll as “forgotten.” Indeed, in its day, the effect was very widely felt. Yet the strange aspect here is now little of a historical footprint this rampaging illness made. It seemed to disappear into distant memory very quickly. It was certainly a sledgehammer blow at the time. A nasty strain of the influenza virus had developed among the trench-bound soldiers of World War I and traveled with them as they journeyed home. It was an ugly parting shot from that devastating war. Each stricken locale blamed it on somewhere else (hence the “Spanish flu” moniker; Spaniards called it the “French flu”), even though epidemiologists have never been able to determine a Ground Zero for the virus. This flu was particularly severe. Most flu epidemics have a mortality rate of a tenth of a percent (meaning one out of every 1,000 infected persons dies). In 1918, the mortality rate worldwide was 20 percent—one out of every five. Badly affected victims would hemorrhage from the nose, stomach, and intestines. Secondary deaths killed even more, as bacterial pneumonia developed in compromised patients. Unusually, the young and vigorous were hit hardest. This is partly explained by hardiness in the older population: An earlier flu pandemic in 1889 to 1890 had left its survivors with partial immunity. Another factor was the manner in which the Spanish flu killed—it caused cytokine storms, overreactions of the immune system which ravage the body. The stronger the immune system, the stronger the overreaction. The felling of the youthful only added to the skyrocketing economic and demographic cost of the pandemic, as fewer fit caretakers were left to tend to the ill. Many of the best health and sanitation workers were among the afflicted, and public authorities were overwhelmed. The sheer number of sick was more than any nation’s health system had been designed to bear. Countries without systematic hospital systems were even worse off. From Peru to the Arctic Circle, people were dying in droves—with the flu claiming three to five percent of the world’s population in an 18-month period. Yet there are few memorials to the event, and general interest in it subsided after the deaths stopped. One reason for this was the rapid, distributed nature of the pandemic—it killed suddenly in one area and then moved on, making it seem like other epidemic outbreaks that populations had experienced, if an especially nasty one. The enormity of the flu’s toll is best seen when analyzing the impact at a national or worldwide level, which most people simply did not have the opportunity to do. Moreover, the flu came on the tail of the world’s most devastating conflict to date; many people seemed to regard it as an accessory of the Great War tragedy, and the flu did not make a separate psychological impression upon them.[2]

8 The Vaal Reefs Mine Disaster

Another modern disaster, this time in South Africa, is notable less for its death toll (at 104 deaths, the smallest on this list) than for its extremely bizarre circumstances. It combines the worst aspects of a mining disaster, an elevator failure, and a locomotive crash. Mining is a major industry in South Africa, and some of the mines there are truly massive. The company AngloGold Ashanti maintains a large gold mine in the town of Vaal Reefs, so huge that internal locomotives are used to move workers, machinery, and ore back and forth on different lateral levels. These levels are, of course, served by vertical shafts that connect them to the surface and to one another. On May 10, 1995, 104 night shift workers were going up the #2 Shaft in a large elevator cage, ready to head home. They never got there. Above them, in circumstances that remain unclear, a driver lost control of a locomotive and jumped clear. Switches designed to stop the engine if it was driverless failed, and multiple safety barriers could not stop the accelerating vehicle. It broke through and plunged straight downward, landing square on the ascending elevator. The winch cable broke instantly, and the two vehicles plunged together for 460 meters (1,500 ft), all the way to the bottom of the shaft. Anyone aboard who wasn’t killed in the initial impact was crushed when the whole plummeting mass hit the shaft floor. Would-be rescuers who found the elevator cage reported that it had been compressed to half its normal size. Recovery efforts were particularly grisly. As a supervising government official described it: At the moment they are cutting through the cage with blowtorches and they must take out a hand here, a foot there and bits of body and wrap it all up and bring it up to the surface. It was immensely sad to see human flesh mingled with steel two kilometres underground. And that is their grave. [ . . . ] It is something I will never forget.[3] Though some regulatory reforms and victims’ pensions resulted from the tragedy, most of South African and the world moved on. Vaals Reefs is best remembered by victim’s families, the local mining industry, and the Guinness Book of World Records—which records that May 10 as the date of the worst elevator accident in history.

7 The Aberfan Disaster

Continuing the theme of bizarre mining disasters brings us to Wales in the 1960s. There, a mining catastrophe claimed the lives of 144 people—all of them above the ground. The Welsh village of Aberfan is nestled in a valley overlooked by a coal-rich mountain range. In 1966, it had a population of 5,000, most of them employed in the coal mines. Looming directly over the streets was a “spoil tip,” a heap of waste material removed during the mining process. The British National Coal Board had approved the location of the tip, despite its proximity to the town. The problem was that heaps of spoil are inherently less stable than virgin rock and vulnerable to liquefying after becoming saturated with water. Ominously, the tip was located over a natural spring, whose presence was well known to the NCB. On the morning of October 21, Aberfan had just received three weeks of historic rainfall. Miners had just noticed slippage along the surface of the tip. And Pantglas Junior High School, less than 900 meters (3,000 ft) away, had just started classes for the day. With booming thunder, roughly 110,000 cubic meters (3.9 million ft3) of spoil slurry began sliding down the mountain, a rapid half-flood, half-avalanche that engulfed the western edge of the village. Outlying farmhouses were obliterated, broken water mains added to the flow, and the school was swamped with debris. The choking, stinking mass flooded into the classrooms, flowing swiftly through doors and windows and quickly resolidifying into solid matter once it stopped moving. When the booming avalanche stopped, an awful stillness welled up. As one of the trapped survivors remembered bitterly: “In that silence you couldn’t hear a bird or a child.”[4] A mound of solidifying debris more than 9 meters (30 ft) high covered the area. The lucky people were trapped in debris up to their waists or necks. 114 people in the school—all but five of them children—were not so lucky. Miners streamed down from the mountainside, anxious to dig the children—including their own—out of the rubble. Their experienced efforts were impeded by other horror-stricken rescuers, whose frantic digging attempts had to be restricted lest they destabilize the whole mass again. No survivors were found after 11:00 AM. A later inquiry faulted the NCB and several employees for creating the preconditions for the disaster, but no prosecutions or penalties resulted. Aberfan’s coal mine continued to operate until 1989. The tragedy is best remembered in Aberfan itself, where a memorial cemetery is located, and remains well-known in the UK. But the catastrophe is still little-known in the rest of the world.

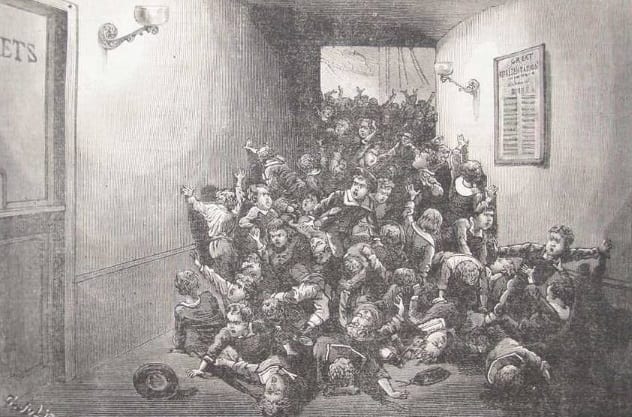

6 The Victoria Hall Stampede

While we’re in Great Britain, we can examine an earlier disaster of similar scope and horror. Here, too, children were the primary victims—and the primary factor. The only avalanche at Victoria Hall was a human one. In the summer of 1883, Victoria Hall, a theater in Sunderland, England, was hosting a children’s variety show. More than 1,000 children aged three to 14 were in attendance, many in the upstairs gallery seats. All was going well until the end of the show, when the entertainers began passing out prizes to some children in the audience. Those in the gallery were worried about missing out. So they started to run. However, the door at the bottom of the staircase opened inward—and worse, it had been bolted mostly shut, leaving a gap so small that only one child could pass through at a time. This measure was apparently intended to ensure that tickets could be properly checked. It made the staircase a death trap. The children who made it to the bottom first could not clear the way or warn those coming behind—so successive waves kept coming. The crushing tide was irresistible. As one child later recalled: “Suddenly I felt that I was treading upon someone lying on the stairs and I cried in horror to those behind ‘Keep back, keep back! There’s someone down.’ It was no use, I passed slowly over and onwards with the mass and before long I passed over others without emotion.” Adults rushed to free the door but could not get at the bolt (also on the children’s side of the door) to do so. Eventually, a strong man wrenched the door from its hinges—only to find 183 little corpses on the other side.[5] At the time, the tragedy sent shock waves of horror throughout Great Britain. A disaster fund was set up—to which Queen Victoria contributed—and a memorial was raised in a park across the street. Outrage at the circumstances even led to legal changes. Soon afterward, push-bar (or “crash-bar”) doors became required for all public venues in Great Britain, a requirement that would soon be repeated throughout the world. While the requirement remains, knowledge of the instigating disaster faded. The memorial, a statue of a grieving mother holding a dead child, degraded and was eventually vandalized. Admirably, it was restored in the early 2000s, and local historical groups have preserved some remembrance of the event for the future. The next time you use a push bar, remember Victoria Hall.

5 The Great Smog Of London

Alongside stampedes, avalanches, and locomotive crashes, air pollution sounds unimpressive as a culprit for disaster. Even those who are aware of the problems of poor air quality tend to think of it as a low-grade or slow-motion problem. But such pollution managed to rack up extreme casualties in the capital of England in 1952. Londoners are used to fog, but in early December of that year, the residents noticed an unusually dense, yellow-black cloud settling over everyone and everything. People could barely see in front of their faces; many compared the experience to being blind. Walking out of doors meant shuffling along with hands outstretched, feeling for obstacles. For four days, public transportation ground to a halt, ambulance service was suspended, and even events in large interior spaces were canceled, as the smog penetrated within.[6] There was no panic—but everywhere, the insidious effects mounted. Hypoxia and respiratory infections multiplied, with acute bronchitis or pneumonia resulting. The very young died, as did the very old or those with prior respiratory problems. When the smog finally cleared due to a shift in wind, authorities realized that over 4,000 people had died in the four days it had blanketed the city. Death rates trended high for months, inflated by smog-related complications. Modern research indicates the final death toll might have reached 12,000, with many more people suffering permanent health effects. It was a cruel but simple combination of factors that caused the smog. Low-grade coal burned in residences, buildings, and power plants, all of which were poorly regulated at the time. Vehicle exhaust added to the fumes, and air masses settled in such a way as to trap noxious gases close to the ground. Some researchers even theorize that these conditions allowed concentrated sulfuric acid to accumulate at ground level. As with some other distributed disasters, the true impact of this one was known best by health officials and regulators who took the time to gather and interpret huge amounts of data. Many of those who lived through it, or even lost loved ones because of it, may still not understand the enormity of the event.

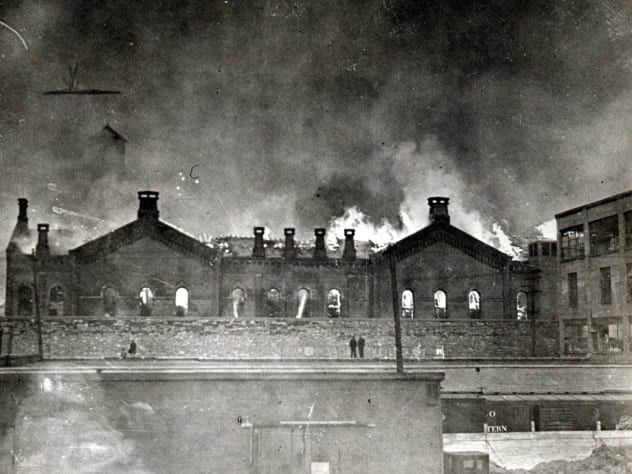

4 The Ohio Penitentiary Fire

If hundreds of people burned to death in your average government facility, you’d get a ton of headlines. But if these people are “involuntary guests of the state” at a prison, those headlines will be converted to footnotes with disquieting speed. The overcrowded 4,300 prisoners had just been locked in their cells on the evening of April 21, 1930, when a misplaced candle started a fire on the roof of one of the main cell blocks. The criminals, trapped before an advancing conflagration, clamored to be let out and allowed to save themselves. Some guards responded in humanitarian fashion and unlocked cell doors, but many more refused to do so.[7] As the human drama unfolded, the fire only grew. One narrow survivor remembered: “There was nothing to do but scream for God to open the doors. And when the doors didn’t open, all that was left was to stand still and let the fire burn the meat off and hope it wouldn’t be too long about it.” Some men began killing themselves rather than be cooked alive. Other desperate inmates managed to overpower a guard, take his keys, and begin releasing their fellows. Only a few dozen were saved this way; suffocating smoke stymied the rescuers, and soon, the flaming roof collapsed on the cell block. Angered over the mistreatment, surviving prisoners who had escaped their cells started to riot, hurling rocks at both guards and firefighters attempting to get close to the blaze. This created a standoff as prison authorities focused on containing the riot rather than the fire. Hundreds of military personnel were called in to restore order, even as the flames rose ever higher. By the time the ash settled, 322 inmates were dead, and another 230 were injured. Newspapers at the time called the tragedy preventable, and some prison reform did result, in the form of the Ohio Parole Board, established in 1931. But there was no grand memorial or outpouring of public sorrow for the deceased. The most vital memory of the disaster was buried with them, and today, few people (aside from Ohio history buffs) have ever heard of that fiery April day.

3 The Salang Tunnel Incident

Our next calamity combines noxious gases, fire, and military silence. It is so shrouded in secrecy that details are sketchy, even nearly 40 years after the fact. In 1982, Soviet military forces in Afghanistan were embroiled in a seemingly never-ending war with fierce local resistance fighters, the mujahedeen. Hindered by extremely inhospitable geography, the campaign saw units constantly compromised by their isolation and the surrounding terrain. At the frigid Salang Pass in the Hindu Kush mountain range, a terrain improvement (a 2.7-kilometer [1.7 mi] road tunnel) became the scene of a disaster. All analyses agree that a Soviet military convoy was moving south through the tunnel on November 3, 1982, and that some fatal crisis occurred. Here, the accounts diverge. Some say a fuel tanker exploded, due either to a traffic accident or a mujahedeen attack (though local insurgents denied any role). Others say there was no explosion, only a traffic jam when two convoys tried to pass one another. But all accounts report that deaths began occurring rapidly thereafter.[8] Fire—if present—would have leaped from vehicle to vehicle, consuming flammable materials and fuel tanks and roasting people alive. It would also have quickly used up the oxygen in the tunnel, leading others to die of asphyxiation. On the other hand, Soviet military records claim that scores of people—Soviet soldiers and Afghans alike—died merely from carbon monoxide poisoning due to the many vehicle engines left running in the confined space. Death presided, though the number of dead is hotly disputed. Low estimates place the death toll at 100 to 200; high estimates reach as many as 2,700. Either way, life was cheap that day in the dark confines of the Salang Tunnel. Whether it was an embarrassingly tragic accident, a successful attack by insurgents, or some combination of the two, the mysterious Salang Tunnel incident remains (arguably) the deadliest road accident in history.

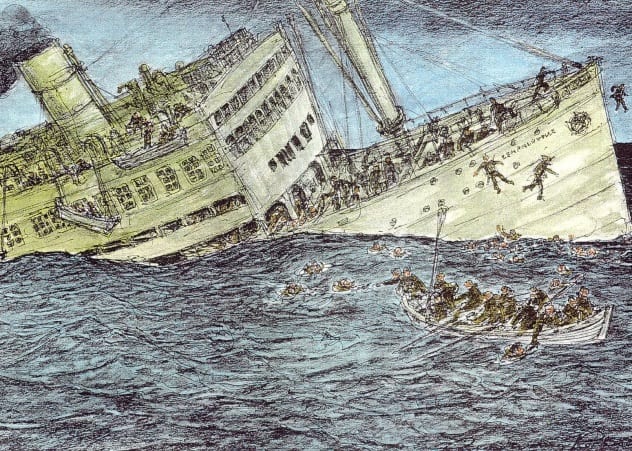

2 The SS Leopoldville

Continuing the military secrets angle . . . RMS Titanic’s sinking was so disastrous, in part, because of its remote location. More people could have been saved, if only there had been sufficient (and attentive) ships nearby. But a generation later, another ship went down with major casualties in the center of one of the world’s busiest sea lanes, the English Channel. And almost no one at the time heard about it. It was Christmas Eve 1944. Rather than tucking themselves in for a long winter’s nap, however, men of the US 66th Infantry Division were hurrying aboard a Belgian transport ship, the SS Leopoldville. The ongoing Battle of the Bulge was in full-on crisis mode, and the 66th was part of the reinforcements being rushed to the front. Everything about the operation was hasty: the disorganized loading of the men, the poor excuse for a lifeboat drill, and the totally insufficient number of life jackets. When a surviving German U-Boat launched two torpedoes at the Leopoldville just before 6:00 PM, the stage had already been set for a disaster.[9] Roughly 300 infantrymen were killed instantly in the torpedo explosion or the immediate flooding which followed. Yet many more preventable deaths occurred. Evacuation orders were given in Flemish, which none of the American troops understood. The majority of crew members departed in lifeboats without encouraging the servicemen to follow. Most escort ships busied themselves searching for the U-boat, with only one (the destroyer HMS Brilliant) pulling alongside the stricken Leopoldville. Yet the massive size difference between the ships (Brilliant being much smaller) meant that the rescue ship could only take off about 500 men, and these had to clamber dozens of feet down the side of the sinking Leopoldville on scrambling nets while the heaving sea conditions hampered the effort. As one Brilliant crewman remembered: Some men had started to jump down from a height of approximately 40 feet. Unfortunately limbs were being broken when they landed on the torpedo tubes and other fixed equipment on the starboard side of the upperdeck; some men fell between the two vessels and were crushed as the two vessels crashed into each other. Leopoldville took more than two hours to sink. Several hundred Allied vessels were only 8 kilometers (5 mi) away in Cherbourg harbor, but most crewmen and radio operators were off duty at holiday parties. This fatally impeded the rescue operations. More than 500 men went down with the ship, with another 250 dying in the water or shortly thereafter. Most of these died of hypothermia. Yet no newspapers carried headlines for the sunken transport, and no radio broadcasts listed the names of the dead. The reason was military secrecy. Wartime censors carefully blocked evidence from reaching the home front, to avoid demoralizing people or encouraging enemy resistance with news of the disaster. Survivors discharged at the end of the war were told not to talk about the incident, or they would lose their veterans’ benefits. It took many decades for the truth to become known—and it still remains underappreciated, even today.

1 The SS Cap Arcona

What could be worse than a boatload of soldiers drowned before they ever got the chance to fight? How about two boatloads of concentration camp survivors sunk by their own would-be rescuers? In the choppy waters of the Baltic Sea on May 3, 1945, four German transports were steaming hard for Norway. Even as the Third Reich collapsed into ash, the architects of the Final Solution were sticking to their tasks. To that end, they loaded nearly 10,000 concentration camp prisoners aboard several vessels, including the converted ocean liner SS Cap Arcona. Forebodingly, the ship had seen prior use as an on-location set for the Nazi propaganda film Titanic (1943). The decks of the Cap Arcona, so recently used to reenact a dreadful sinking, were about to experience the real thing. Allied forces, having received word that high-ranking Nazi SS officials were attempting to flee to neutral territory in Scandinavia, were eager to prevent this. Sighting the German prison flotilla—whose ships were not marked to signify their purpose, with prisoners locked out of sight belowdecks—British spotters assumed they were fair game and called in the fighter-bombers. The fat, slow, unprotected German ships made easy targets.[10] Horrific chaos reigned aboard the Cap Arcona. The Titanic’s often-exaggerated sealing of lower class passengers in the belly of the ship played out with appalling reality—SS guards ignored the cries of locked-in prisoners, appropriated life jackets for themselves, and abandoned ship. Many people, unfortunates who had endured months at Sachsenhausen and other death camps, were either burned alive in the spreading fires or entombed in the water-filled depths of the vessel. Of those who made it to the open water, most were ignored by German rescue ships—which focused on rescuing SS guards—while British aerial 20-millimeter cannons strafed the scene. As one pilot remembered: “We used our cannon fire at the chaps in the water . . . we shot them up with 20 mm cannons in the water. Horrible thing, but we were told to do it and we did it. That’s war.” Some prisoners who made it through the maelstrom, still strong enough to swim, made it to the beach—where they were massacred by armed Hitler Youth members. In the end, only 350 of Cap Arcona’s 5,000 prisoners survived the day. With 2,750 additional dead from the accompanying Thielbek, it made for nearly 8,000 fresh corpses bobbing in the Baltic. It’s hard to imagine the anguish of the British pilots upon learning that they had inadvertently killed so many of the people they were trying to liberate. Yet it must have paled in comparison to the anguish felt by the doomed prisoners in their final moments. They’d survived years of incredible privations, only to die now in sudden, inexplicable fashion. Most probably never knew the full extent of the tragedy—only their small, terrifying portion of it. Most of the general public has never heard of it, either. Almost everyone involved had reason to forget: the Germans to deflect or mitigate the memory of their Holocaust guilt, the British to limit embarrassment at what was essentially a grand mal friendly fire issue, and the few survivors to exorcise the demons of one horrific incident among many. The few small memorials to the sad victims of the Cap Arcona are scattered among local cemeteries in Germany. David F. Ellrod lives in Maryland with his wife, three children, and one very excitable dog. You can reach him at https://ourfamilycanvas.wordpress.com/ or on Twitter @DavidEllrod.