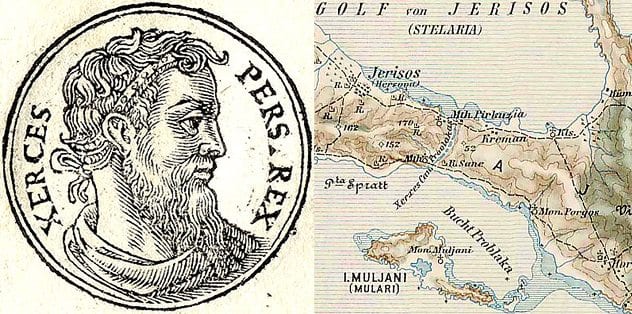

Most people today know it through the story of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans—but that was just a small moment in a much bigger war. The real story revolved around the Persian King Xerxes—and it was a bit different from how you might be picturing it.

10Sparta Apologized for Throwing a Messenger down a Well

That famous moment when the Spartans kicked a Persian messenger down a well really happened—but a lot of details got left out, and they will completely change the way you see it. Xerxes’ father sent messengers to every ruler in Greece demanding a tribute of earth and water as a show of submission to Persia. It was not just the Spartans who refused—the Athenians threw their messenger down a pit, too. They had the courtesy to give him a trial first, though. The Spartans just told him to “Dig out Sparta’s earth and water yourself!” and threw him in. By the time Xerxes became king, he did not even bother sending messengers to Athens or Sparta. He did not have to, anyway. The Spartans came to him and said they were sorry. After throwing the Persian in the well, the Spartans became convinced that they were cursed. The gods stopped answering their prayers, and they were pretty sure it was because they had mistreated a messenger. So, to make the gods happy, they sent two human sacrifices to Xerxes. They apologized and offered to let him execute them to even the score. Xerxes spared them. Partly, he was trying to take the high road, but mainly he just had his mind set on revenge. “The death of two men,” he told them, would not “acquit the Spartans from the guilt they have contracted.”

9The Greeks Practically Begged Xerxes to Invade Them

Xerxes, originally, wanted to leave Greece alone. His father had led a long and painful campaign against the Greeks and lost, and Xerxes was not eager to follow in his footsteps. Some of his generals pushed for him to go to war, but he was not going to listen to them—until the Greeks asked him to. A lot of Greeks actually loved Persia. They thought they were an incredibly diverse and progressive nation. Some of them were so eager to become a part of the empire that they actually came to Persia and asked Xerxes to be their leader. First, the Aleuadae family came over and offered to pay Xerxes to come to Greece. Then another family, the Pisistratidae, came and offered him even more. They even brought an oracle with them, who told Xerxes he was destined to build a floating bridge and conquer Greece. By the time they had left, Xerxes was convinced he was meant to rule Greece. He called together his people and announced that they would be going to war. “I will never rest,” he declared, “until I have taken Athens and burnt it.”

8Xerxes Made His Men Whip a River for Misbehaving

Xerxes bought into the prophecy the Greeks gave him. He wanted to play out every moment they described leading to his victory, and so he set up a floating bridge across the Hellespont River. It did not work out—as soon as the bridge went up, a storm knocked it down. Xerxes had some issues with anger. If someone made him mad, he got revenge—even if that someone was a body of water. He ordered his men to put chains on the river and whip it for its insolence. So, they tossed some chains in the water and gave the river 300 lashes, yelling, “You are a turbid and briny river!” It gets weirder. Xerxes, apparently, felt bad about whipping the river, because, once he got his bridge to stay up, he apologized to it. He burned incense on the bridge and threw golden bottles into the water—which, according to Herodotus, was his attempt to apologize to the sea.

7Xerxes Cut a Man in Half for Draft Dodging

Before he crossed the bridge, one of Xerxes’ men, named Pythius, came to him and asked for a favor. He’d had visions that the war would fail, and he feared his sons, who were marching off to war, would die. “Take pity on me in my advanced age,” Pythius begged, “and release one of my sons, the eldest, from service.” Xerxes’ short fuse went off. After cursing Pythius out for a full minute, he barked, “You shall be punished by the life of the one you must desire to keep.” He sent his men out to get Pythius’ son and had him cut in half. One half of his body was put on the right side of the road and the other half on left, so that the army had to march between his severed corpse on the road to Greece.

6Xerxes Tore Down a Mountain Just Because He Could

Before he left for Greece, Xerxes ordered his men to build a massive canal. His father’s fleet had been swept away in a storm when he invaded Greece, and Xerxes did not want to make the same mistake. He ordered his men to plow through a mountain and build a massive, artificial canal that stretched over two kilometers. It took three years of whipping workers to make it, but they did it. They made a canal so massive that the whole Persian fleet could cross it. This was such a massive feat that, until fairly recently, people thought it was a myth. Until land surveyors found proof that it really did exist, we thought it was impossible. The Greeks, though, did not really understand why he was doing it. “With no trouble they could have drawn their ships across the isthmus,” Herodotus wrote about it, pointing to a natural strip of land that would have kept the ships safe. He had another theory. “Xerxes gave the command for this digging out of pride, wishing to display his power and leave a memorial.” If he is right, it worked—the canal outlived its creators.

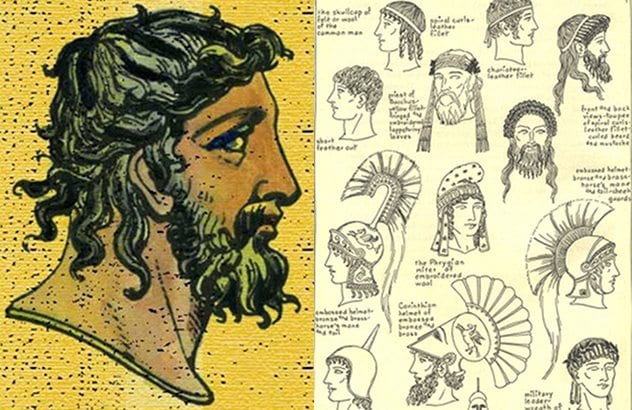

5The Spartans Got Ready for Battle by Making Their Hair Look Pretty

Meanwhile, the Spartans were getting ready for battle in their own way. The Spartan army kept their hair long, believing that long, wild hair would strike terror in the hearts of their enemies. Before battle, they did their exercises and combed their long hair, preparing for war—but that was not exactly how the Persians saw it. Xerxes sent a spy ahead to scope out the Spartan forces, and he was not impressed by what he saw. He reported back that the Spartans were sitting around dancing and making sure their hair looked pretty instead of getting ready for war. A Spartan defector, Demaratus, tried to explain to him that Spartans prepare their hair before fighting. In part, it let them die with dignity, but their thick braids also worked as a type of armor. Xerxes, though, was not impressed. He made a joke about them being sissies and marched on.

4The Persian Army Had Every Bad Omen Possible

As the Persian army approached they saw things that, according to the Greeks, were bad omens everywhere they looked. First, they walked past a mare giving birth to a hare, which, according to the Greeks, symbolized that Xerxes would flee for his life. Then they saw the birth of a hermaphroditic mule, with both male and female genitals. Our source for this is Herodotus, who saw this as such an obvious omen that it is not even worth explaining. “The meaning of it was easy to guess,” he writes, before scoffing at Xerxes because he “took no account of either sign and journeyed onward.” Those omens have lost a lot of their meaning—but anybody would be worried about what happened next. As they marched forward, they started getting attacked by every lion that they saw. Every night, lions would come out of their homes just to kill their camels—and some started to wonder if maybe the gods just did not like them that much.

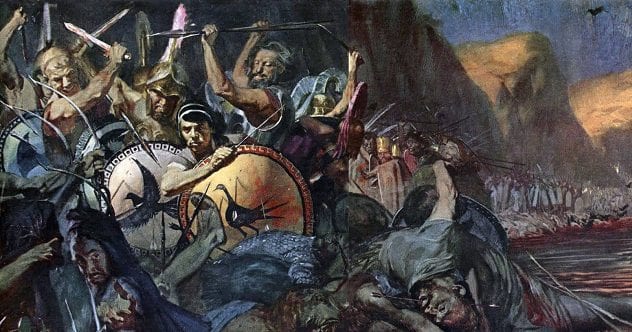

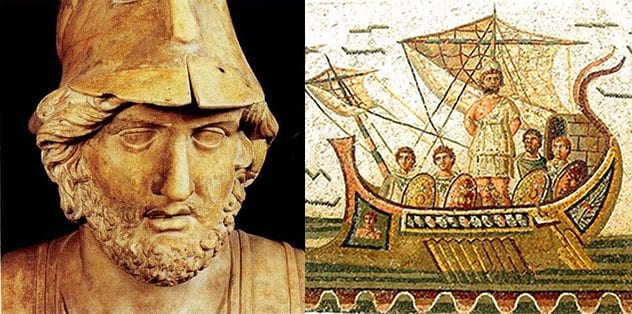

3Xerxes Defiled Leonidas’ Body

The Battle of Thermopylae followed. Leonidas and 300 Spartans met the Persian army and held out against them to the last man. But the story does not end with Leonidas’ death. After the 300 Spartans were defeated, the Persians marched on. They rained arrows upon the Spartans until the last one was dead, and slaughtered every person they could find. They tore down the walls of Thermopylae. Every single Spartan they could find was killed. When Leonidas was shot down, his men-at-arms tried to protect his body and get it to a safe place where it could be put to rest with dignity. Xerxes, though, would not allow it. Once his men had crushed their way through, he had Leonidas’ head chopped off and his body crucified on a spike.

2The Greeks Nearly Lost Because of a Love Spat over a Handsome Boy

Leonidas, though, was not the real hero of the war. The man who really made it possible for the Greeks to win was Themistocles. Before Persia had even set its sights on Greece, Themistocles was building warships to get ready. It was the Navy that really beat the Persians. Themistocles tricked Xerxes into sending his ships into a narrow canal called Salamis, where he surprised him with a stronger defense than he had expected. It was the turning point in the war; the moment that made a Greek victory possible. It nearly did not happen, though, because of Themistocles’ penchant for young boys. He and a man named Aristides had been fighting over the love of a good-looking boy named Stesilaus. Aristides was so mad about it that he fought Themistocles at every turn. Out of spite, he nearly stopped Themistocles from building his navy. Themistocles managed to get Aristides kicked out Athens and built his ships, if he had not, the Persians would have won—all because of a spat between the jealous lovers of a young boy.

1Themistocles Joined the Persian Army

This war changed all of Western history. Had it not been for Themistocles, Greece never would have developed into the philosophic cultural cornerstone it became. He saved Greece—and then, promptly afterward, switched sides. After the war, Themistocles worked on building up the Athenian military to get them ready to fight the Spartans. The Spartans found out and, in retaliation, spread rumors that he was planning on betraying Athens to the Persians. It worked. The Athenians kicked him out. Frustrated, Themistocles decided that if they thought he was helping the Persians, then maybe he should just do it anyway. He sailed off to Persia and spent the rest of his life as a Persian governor. He worked for Xerxes’ son until the very end, serving the army he had once defeated. Mark Oliver is a regular contributor to Listverse. He writing also appears on a number of other sites, including The Onion’s StarWipe and Cracked.com. His website is regularly updated with everything he writes. Read More: Wordpress