Often, it was society that would make up parents’ minds for them, as beliefs on how best to feed babies changed many times over thousands of years. Advertising was a major factor, and the safety of a given food choice was paramount. Here is an overview of what people decided to feed their children over the last several thousand years.

10 Wet Nursing

The use of a wet nurse was common before feeding with formula or bottles was introduced. It began as early as 2000 BC and continued up until the 20th century. Throughout this period, whether a mother decided to use a wet nurse or not was determined by either need or choice—some mothers had no alternative, as they couldn’t produce milk themselves. Wet nursing was a profession that involved contracts and legalities to regulate the practice. The introduction of the feeding bottle in the 19th century as an alternative helped to do away with the practice of wet nursing. In Israel around 2000 BC, children and breastfeeding were considered a blessing, and the act was even viewed as a religious ceremony. In the Papyrus Ebers, an ancient Egyptian medical papyrus, advice for failed lactation in mothers included “warming the bones of a sword fish in oil” and rubbing it on the back of the mother.[1] Alternatively, she may sit with crossed legs eating bread “soused in durra” (a kind of millet) while rubbing her breasts with the poppy plant.

9 Classical Antiquity

Women of higher status demanded wet nurses with great frequency in Greece around 950 BC, and after a time, the wet nurses held positions of higher accountability and even had some authority over the household slaves. The Bible refers to a few examples of wet nurses, probably the most famous being the nurse who was hired by the pharaoh’s daughter to breastfeed Moses, who was found in the bulrushes.[2] In the Roman Empire from 300 BC to AD 400, contracts were written up for wet nurses to care for abandoned children, usually girls, who were purchased as future slaves by the wealthy. The wet nurses, also slaves, would feed the infants until they were three.

8 The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, advice on how to be a wet nurse came from a 13th-century Franciscan friar named Bartholomeus Anglicus.[3] He recommended that the nurse behave like a mother: “She picks him up when he falls, gives the little one milk when he cries . . . washes and cleans the little one when he makes a mess of himself.” Thank goodness for the advice of Franciscan friars. In the Middle Ages, childhood was once again seen as a fragile and special time, and breast milk was thought to hold almost magical qualities. Once again, mothers were encouraged to feed their own babies breast milk as part of their saintly duty, as it was supposed that breast milk could pass on psychological and physical characteristics to the child. In the Renaissance, this attitude to mothers nursing their own children continued, as they feared infants might prefer the wet nurse to the mother.

7 No Redheads

In 1612, French surgeon and obstetrician Jacques Guillemeau stated in The Nursing Of Children that wet nurses with red hair should not be used because their breast milk could pass on their fiery temperaments. Nurses should instead be “mild, gentle, courteous, patient, sober, chast, not quarrelsome; not chollericke, neither proud or covetous, nor a blabber.”[4]

6 The Later Years

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, wet nursing continued, being favored by the wealthy, who considered breastfeeding their own children unfashionable and feared it would ruin their figures. The clothing of the time prevented breastfeeding and made life harder for those who wanted to continue with socially acceptable pastimes, such as card-playing and attending the theater. Even those in lower classes, such as the wives of doctors, lawyers, and merchants, employed wet nurses, as it was cheaper to do so than to hire someone to run their husband’s business or to run the household in their place. In the Industrial Revolution that followed, many families moved from rural to urban areas, where peasant wet nurses were commonly employed. William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine (1779) displays a clear mistrust for wet nurses who appeared to favor home remedies, especially their use of opiates like Godfrey’s Cordial to give to the baby to induce “quietness.”[5]

5 Early Bottles

In the 19th century, wet nursing began to die out as a profession as animal milk and preferences for bottle-feeding gained momentum. The use of bottles for feeding was popular in ancient times, it should be noted, and vessels have been discovered that are thousands of years old. Grecian terra-cotta feeders from 450 BC were used to feed children a mixture of wine and honey.[6] Many of the containers found were tested and showed traces of milk products, so archaeologists concluded that animal milk or other substitutes were used as far back as the Stone Age. Problems developing around cleaning the bottles are listed in literature from Roman times, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. The Industrial Revolution paved the way for bottles to become hygienic and safe for baby-feeding.

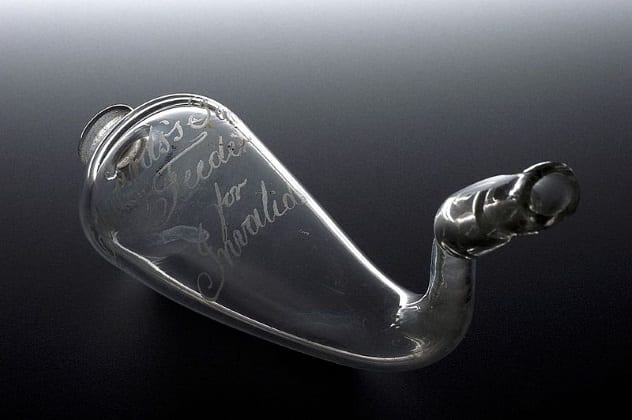

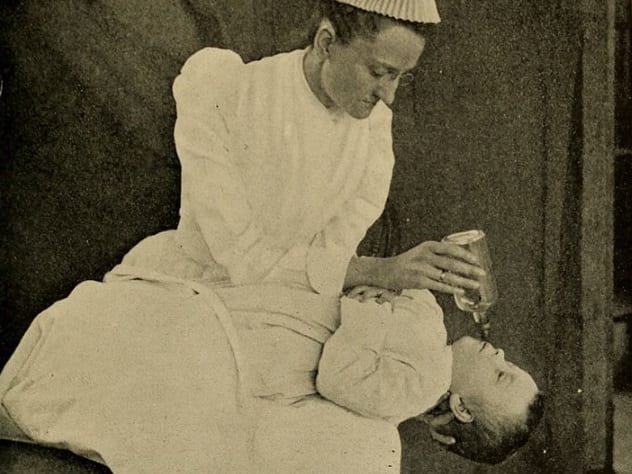

4 Bubby Pots And Pap Boats

Before the modern style of baby bottles was designed, there were many alternatives to chose from. Some were made of ceramics or wood, but the most popular type of feeding device was made from a cow’s horn, perforated to allow the milk to flow through. In the 1700s, pewter and silver were favored, with the most popular being a device called the bubby pot (left above), invented by a physician from London named Hugh Smith.[7] Unfortunately, the spout was nearly impossible to clean and often led to infection and mortality. Pap boats (right above) were just as dangerous, filled with pap, which was bread soaked in water or milk, or panada, which were cereals in broth. Sickly, malnourished babies were given this strengthening food, but as the vessels were so hard to clean that nearly a third of the children died in their first year.

3 19th-Century Bottles

Glass bottles were introduced for feeding in the mid-19th century, and some were very elaborate, blown into cones or gourd shapes, replacing the porcelain that had come before.[8] Many of the new and elaborate designs were subsequently called “murder bottles,” as they became a kind of Petrie dish for bacteria to grow since cleaning the rubber tubes and pipes was very difficult. In one case, an artificial breast was invented that could be filled with milk and worn by the mother all day and night to keep it warm for her child. In 1863, an inventor named Matthew Tomlinson designed a “coloured glass pear-shaped bottle called The Cottage,” which he sold for a shilling and thought was very well adapted to a working man’s household.

2 Early Formulas

In today’s culture, breastfeeding is considered the best source of nutrition for infants, but when formulas were introduced, they did not have current standards of research practices and often fell short of adequate nutrition. Advertising grew public interest toward alternative milk sources, and throughout the 19th century, animal milk was preferred and added to pap and panada when the baby was sickly. Comparisons between animal and human milk were studied in the 18th century according to what animal was available to a community, such as horses, pigs, camels, donkeys, sheep, and goats. Cow’s milk was preferred overall. In 1865, a “perfect” infant milk composite was designed to mimic the content of human milk. Called Liebig’s formula, it consisted of cow’s milk, malt, and wheat flour, with potassium carbonate.[9]

1 Improvements And Increased Safety

By the end of 1883, 27 patented varieties of formula had become available following Liebig’s brand, but many were not nutritionally adequate, although sugar was added to increase caloric intake. Over time, knowledge regarding vitamin fortification allowed for the formulas to be more effective. Formula was most popular during the summer, when milk would spoil, and infant mortality rose, alleviated only with the acceptance of germ theory between 1890 and 1910. As cleanliness improved, and rubber teats were more available, mortality declined. Also, as more and more homes had iceboxes, milk could be safely stored for later use.[10] Alexa is a writer and clog dancer living in Dublin, Ireland.