However, some organisms are so harmful to humans and other animals that the world might be better off without them. Though the practice of “planned extinction” is controversial, many scientists believe that the benefits justify the purposeful eradication of some species. Here are 10 animals that scientists and public officials around the world are trying to wipe from the face of the Earth.

10 Mosquitoes

If you’ve ever imagined a world without these little bloodsucking pests, you are not alone. But mosquitoes are more than an itchy annoyance. They can also be a vector for the transmission of deadly diseases to humans—such as malaria, a blood parasite that infects as many as 216 million people per year, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. The primary carrier of malaria is a mosquito by the name of Anopheles gambiae. For at least the last 30 years, some scientists have been toying with the idea that the best way to eliminate the disease is to kill off the mosquitoes. But no one knew how this could be accomplished until recently. Since the development of new gene-editing technologies in the past few years, a team of scientists working with Oxford University has genetically modified a strain of A. gambiae mosquitoes to carry a dominant gene that could cause the females of the species to become infertile over time. If these altered mosquitoes were released into the environment, the scientists believe that they would begin breeding with the wild population, producing entire generations of individuals incapable of reproduction. Given enough time, the infertility gene could spread widely enough to rid entire continents of A. gambiae and possibly wipe out the entire species worldwide. But if the idea of intentionally causing the extinction of a species makes you uneasy, there’s a good reason for that. For one, removing a species from the ecosystem can have unintended consequences. Animals that used to prey on that species might end up going hungry, for instance. Second, many in the scientific community have pointed out that gene-splicing technology hasn’t been sufficiently tested and releasing altered genes into the wild would be irreversible.[1]

9 Guinea Worm

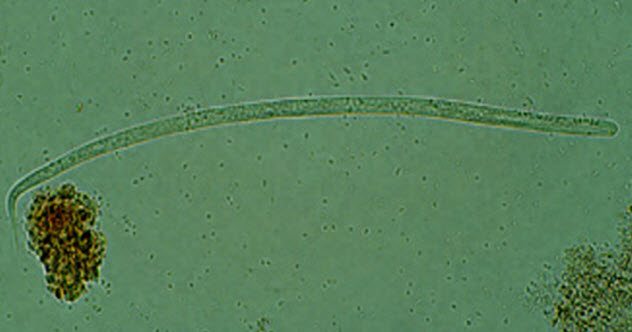

This parasitic worm lives up to its monstrous name, Dracunculus medinensis, by causing an extremely painful and horrifying disease. The larvae of the worm enter their human hosts via contaminated drinking water from lakes, rivers, or ponds. Once inside the digestive tract, male and female larvae pass through the thin tissue of the intestinal lining and mate. The male dies shortly after, but the female moves into position just under the skin, usually in the lower leg of her victim. Coiled beneath the skin, she can grow as long as 76 centimeters (30 in). About a year after arriving in her host, the female worm creates a painful and itchy blister on the skin through which she emerges inch by excruciating inch over the course of several days or weeks. The pain and discomfort of the emerging worm often causes infected people to bathe the wound in water, where the female expels thousands of eggs and perpetuates the cycle of infection. In the 1980s, the World Health Organization (WHO) began efforts to eradicate the Guinea worm. They have nearly succeeded, with only 30 reported cases of infection in 2017. Efforts to end the disease include treating active infections and distributing water filters to communities vulnerable to exposure as well as educating the population on the importance of not drinking untreated water. Although human infection is steadily declining, the worm was recently discovered infecting dogs. So, total extinction may not be in the cards for this painful parasite.[2]

8 Wuchereria bancrofti

These parasitic roundworms are spread by mosquitoes and can grow up to 10 centimeters (4 in) long. As adults, they reside in the ducts of the lymphatic system of human hosts. The blockages they cause in the host’s lymphatic system can trigger the debilitating and horrifically disfiguring disease known as elephantiasis, an extreme swelling of the lower extremities, breasts, or testicles. WHO estimates that as many as 120 million people are infected worldwide. One species in particular, Wuchereria bancrofti, is the most common cause of elephantiasis, and this species is only known to infect humans. Eradicating the disease in humans would result in the total extinction of this species of worm, and the WHO has been attempting to do just that since 1997.[3] Efforts to eradicate W. bancrofti focus on treating entire populations, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, with deworming drugs on a yearly basis. So far, the WHO has been largely successful in their efforts. Of the 73 countries they identify as being endemic for worm infection, 40 countries are listed as on track to achieve total elimination.

7 New World Screwworm

The New World screwworm is actually the larval stage of a species of fly, which probably doesn’t make you feel any more sympathetic to this flesh-eating parasite. The life cycle of this species begins when a female fly lays eggs in or near an open wound on a human or other warm-blooded host. When the eggs hatch, the larvae burrow into their host’s flesh, leaving behind open lesions. Screw worms were once common throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of North and South America. But in 1972, a joint effort between the United States and Mexico eliminated the bug within their borders. They used a method called sterile insect technique, in which male flies were “castrated” by dosing them with radiation in a lab. The sterile males were then released into the wild where they mated with females but failed to reproduce. This led to sudden and massive declines in their population.[4] The US still maintains a lab at the border of Colombia and Panama that releases sterile males to prevent the species from advancing north again. But the New World screwworm might not be on the ropes yet. In 2016, an outbreak was discovered in deer populations in the Florida Keys.

6 Pubic Lice

Although there is no coordinated effort to drive this insect to extinction, evidence of its decline in recent years is unlikely to land pubic lice (aka “crabs“) on the list of protected species. These tiny bugs are related to head lice and, like their northerly cousins, they only live on human hosts. The difference is that pubic lice can only live in the relatively coarse hairs that line our axillary (armpit) and pubic regions. Pubic lice are spread from host to host primarily by sexual contact. They cause intense itching as they feed on our blood, so we’ve been waging a quiet war on them for millennia. But it’s a modern development that might be their eventual undoing. During the past decade, scientists have observed a drop in the reported incidences of infestation. Some have noticed that it may be due to acute loss of habitat. People are shaving and waxing their pubic hair, reducing the opportunities for transmission of the parasite. But not everyone is sure that pubic lice are in imminent danger. One possible explanation for the lower rate of reported infections might be due to the ease with which people can access nonprescription home treatment methods, which are similar to treatments for head lice.[5]

5 Onchocerca volvulus

This parasitic worm is passed between human hosts by the bite of black flies that live near rivers and streams in Africa, parts of Latin America, and Yemen. Infection by Onchocerca volvulus can cause severe itching of the skin as well as scarring of the cornea that often leads to permanent blindness if not treated. According to WHO, this disease, called river blindness, is the second leading cause of blindness in the world. For the past two decades, the Carter Center has been working with local governments of affected regions around the world to eradicate the parasite. The main weapon in the war against river blindness is a drug called ivermectin, which can kill the worms inside their human host and prevent the disease from spreading.[6] The efforts have been largely successful in South America, where the disease is all but gone. But Africa still accounts for 99 percent of all cases of river blindness. WHO estimates that 18 million people are still affected worldwide.

4 Hookworms

Hookworms can enter their human hosts orally when people eat unwashed vegetables with the microscopic eggs attached or when children play in the dirt and put their hands in their mouths. But the most common means of infection is through the skin of the feet. When people walk barefoot on infected soil, the worms can burrow through the skin and enter the bloodstream. Though this parasitic roundworm now exists primarily in tropical areas, it was once common in the South in the United States before mass eradication efforts all but eliminated the pest in the early 20th century. But the worm—and its symptoms of anemia and severe diarrhea—are still common in poverty-stricken areas throughout the world. The animal spreads to new hosts through feces-contaminated soil, so increasing access to basic sewage and sanitation is key in driving this species to extinction. Readily available deworming medications are also effective in killing the worms and stopping their spread.[7]

3 Tsetse Flies

The bite of this small fly can transmit the blood parasite that causes African sleeping sickness, an infection that results in fever, mental confusion, physical weakness, and often death if untreated. But it’s not only the direct effects of African sleeping sickness that harm people in tsetse fly–infested areas. Domestic animals such as pigs, cows, and donkeys are also vulnerable to being bitten and infected by the fly, making farming difficult. Due to the tsetse fly’s impact on the livestock of subsistence farmers in sub-Saharan Africa, the UN believes that the insect is a major driver of poverty on the African continent. If the flies would just buzz off, people in affected areas would be able to more fully use farmland that is now lying fallow. Control efforts—such as pesticide use, trapping, and the culling of wild animals that the tsetse fly feeds on—have been used for decades with minimal effect. But the technique that seems to show the most promise for eradicating the tsetse fly from entire continents is sterile insect technique, the process of releasing radiation-sterilized males into wild breeding populations.[8]

2 Bedbugs

As their name implies, bedbugs are small, wingless, bloodsucking insects that tend to hide in blankets and bedding, just waiting for us to fall asleep so they can come out and feed on us. They have been living alongside humans for thousands of years. Although they became largely uncommon in developed countries during the mid-19th century, they seem to be making a comeback. In recent years, urban areas in the US and Canada have seen outbreaks that have spread quickly and proved difficult to contain, let alone eliminate. That’s because bedbugs are hardy survivors. They can live for months without feeding, often hiding in walls or under floorboards to avoid being seen. To make matters worse, there is evidence that bedbugs are developing resistance to the pesticides that once reliably killed them. Though local governments in the US are increasingly instituting public health initiatives to stop the spread of bedbugs, we might be stuck with them for some time. One of the only sure ways to kill them is to heat the infested environment to above 50 degrees Celsius (122 °F), and that’s just not feasible for many homes.[9]

1 Homo sapiens

Yeah, you read that right. Us. Some people believe that the human species is so destructive that the world would be better off without us. One such person is a man named Les Knight, the spokesman of a group called the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (VHEMT). According to VHEMT, the human species is as good as doomed anyway, so we might as well phase ourselves out now to limit the number of species we take with us. However, their methods aren’t violent or coercive. VHEMT only asks that their members refrain from having children. There is an undeniable, if unpalatable, logic to VHEMT’s goals. If we simply allowed the human species to die out, countless other species likely would be saved from extinction and we would no longer have to worry about the other animals on this list. We wouldn’t be around to be bothered by them.[10] That approach appears to be a hard sell, though, as the world population is currently estimated at nearly 7.5 billion people. It seems that one thing all species may have in common is that they never go willingly to their own extinction.